ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

W RITING THIS WORK WOULD HAVE BEEN impossible without the support of the Department of History at the University of Birmingham and the War Studies Department at the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst. Both of us benefited from lengthy periods of study leave, which provided the time and space to conduct research and pen the book. In particular, Dan would like to thank successive heads of school Corey Ross and Sabine Lee, and heads of department Nick Crowson and Elaine Fulton, for their support. Stuart would like to thank his departmental colleagues for their wisdom and camaraderie and specifically thank Duncan Anderson, Chris Mann, James Kitchen and Klaus Schmider who provided valuable advice at key moments. We both owe a tremendous debt of gratitude to the staff of the libraries and archives that have supported this book. Specific mention must be made to Andrew Orgill and John Pearce of the RMAS library whose knowledge and tireless work provided immeasurable assistance to us, and the ever-helpful staff at The National Archives and British Library.

We both realise that we are fortunate to have some incredible academic colleagues and mentors who have offered their insights and encouragement throughout this project. We would like to thank Gary Sheffield, John Bourne, Stephen Badsey, Spencer Jones, Aime Fox, Matthew Ford, Alan James, William Philpott, Jonathan Boff, Jonathan Krause, Paul Ramsey, and Christopher Duffy. We would also like to offer our thanks to Clare Litt, Ruth Sheppard, Isobel Fulton, Alison Boyd and the staff of Casemate Publishing who have been diligent and patient with us during the complicated publication process.

Our friends and families have been amazing. Stuart would particularly like to thank Chris McDowall, Sarah Acton, Andrew Slater, Kelly and Dan McNicholas, Abigail Thomas and Snowy for providing a Manchester sanctuary away from writing. We would both like to show our appreciation to Fotoula Hatzantonis, who has been a source of enduring strength and always there to offer kind words of encouragement. Stuart would like to acknowledge Abe, his little black cat, who was often perched on his shoulder while writing, and most importantly his mother, Amanda Taylor, whose patience and understanding made this book possible. Dan would like to thank his family for their constant support. Dan wrote most of the drafts of his portions of the book while away in Turkey: he would like to thank Orhan amca, Canan teyze, Aye teyze, and Ece for their hospitality during his stay. Most of all, he would like to thank his wife Gnen for her love and support.

INTRODUCTION

Mission Accomplished

Banner on the USS Abraham Lincoln , 1 May 2003

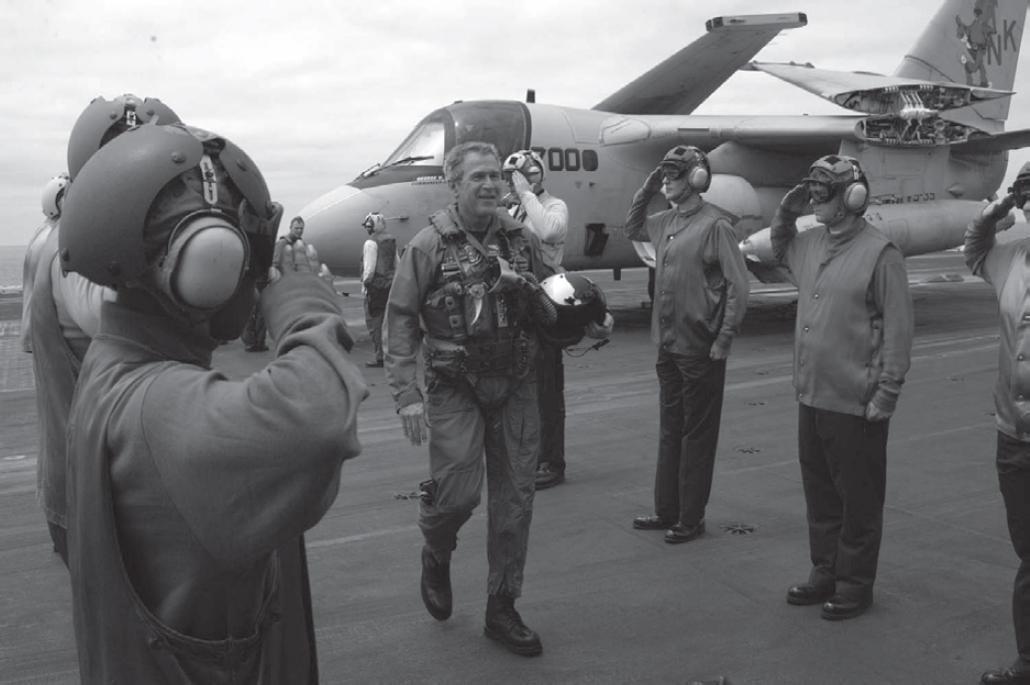

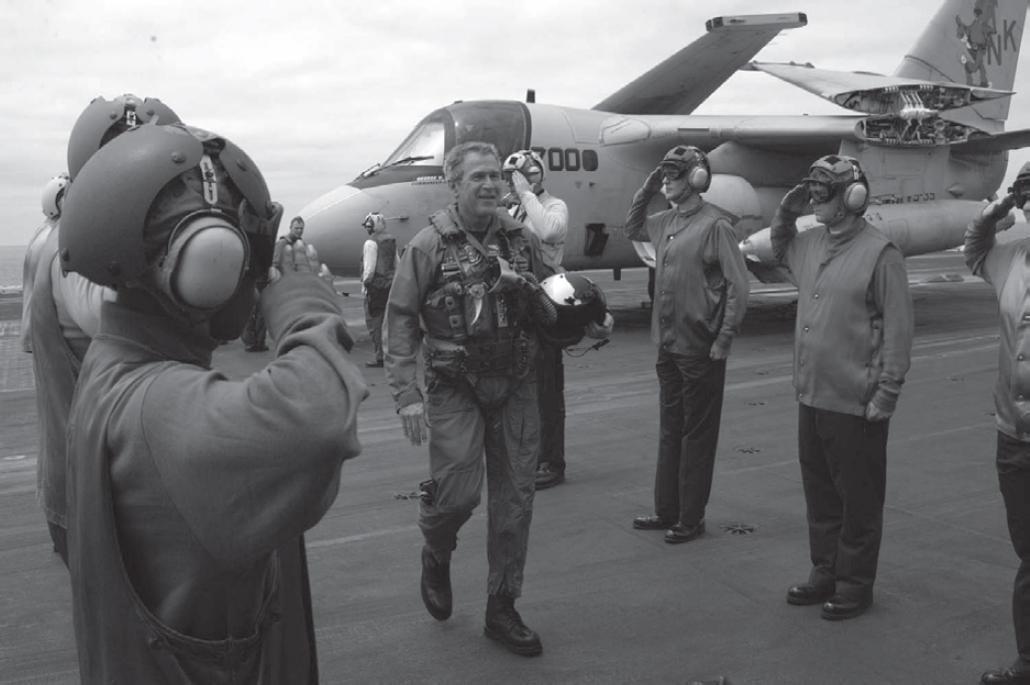

O N 1 M AY 2003 US P RESIDENT George W. Bush touched down on the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln . In a carefully choreographed arrival, he shook hands and had photos taken with the crew and commander of the US Navy vessel, while wearing a military flight suit. He had not flown the S-3B Viking jet which arrived on the carrier but that mattered little. The message was clear: Bush was a president who got things done. Later that same day, now in a more traditional black suit, the president stood in front of the assembled navy crew and world media with a mission accomplished banner adorning the conning tower behind him. His speech left a clear sense that the war in Iraq was coming to an end. Major combat operations in Iraq have ended. In the battle of Iraq, the United States and her Allies have prevailed. Clapping and cheers erupted from the crowd of serving sailors. The message resonated; they were coming to the end of the longest deployment since Vietnam ten months. The camera promptly cut to the banner. The hard work had been done.

George W. Bush on the deck of USS Abraham Lincoln

As Bushs speech continued, he emphasised the precision, speed and boldness of the American forces attack. They had destroyed enemy divisions from a great distance, while Marines and soldiers sped across 350 miles of hostile ground. Despite paying lip service to the security and reconstruction task they now faced, the president had described Operation Iraqi Freedom in traditional, conventional terms. But the war had already begun to change. Mass gatherings took place in Fallujah on 28 and 30 April 2003, leading to indiscriminate shooting by the US airborne troops stationed in the city. Thirteen civilians were killed and 91 injured. More widely, rioting and looting began breaking out. Iraq was fracturing along sectarian lines and radical elements began to move in to exploit the lawlessness. In response, most senior American political and military leaders attempted to wage conventional war on an unconventional opponent. They failed to understand the changing environment. They failed to understand that they were now facing a nascent insurgency.

Understanding the characteristics of the war being fought is integral for any commander or politician. Insurgencies can evolve in parallel to conventional operations, using a variety of tactics and methods. Their clandestine nature can obscure the danger posed to existing civil, military or social structures. Civil disorder can bleed into rioting, which might end up leading to more organised resistance. Militaries and politicians alike have frequently struggled to switch from a mindset of conventional operations to stabilisation and development. In 2003, President Bushs triumphalism made him a hostage to fortune. Iraq was already a fertile ground for an insurgency. It was a decision he came to regret in 2008 when he admitted in an interview with CNN that: It conveyed the wrong message. But the failure ran deeper than a banner and hubris. Iraq was the latest failure of a stronger conventional force to recognise that the war they were fighting had changed.

Insurgencies and counterinsurgencies have been the most common form of warfare throughout the 20th century. Since 1900, the United Kingdom has been almost continually engaged in a succession of small wars. Before 2016, only 1968 was a bloodless year for the armed forces. Yet despite this, these wars have remained largely overshadowed by their more conventional and intensive counterparts. This is understandable: major state-on-state conflicts, such as the World Wars, have led to enormous casualties in absolute terms and in a relatively short period of time. Conventional operations, which see regular forces of one or more states fight another, often have a marked impact on both the militaries and societies of those involved. Counterinsurgencies, on the other hand, can be much more diverse in their impact. They are frequently influenced by regional conditions or the actions of specific leaders, and they have often had ambiguous outcomes. Going further, historians and soldiers alike have struggled to pin down what defines a counterinsurgency campaign. The combatting of an insurgency is so intimately wrapped up with criminality, political violence and terrorism that it has been difficult for experts to agree where one label ends and another begins. This book is our attempt to shed light on this difficult topic and to explore how the theories that have shaped counterinsurgency have frequently smoothed over the difficult realities of these campaigns.