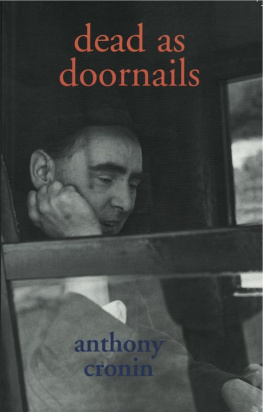

Cronin - Dead as Doornails

Here you can read online Cronin - Dead as Doornails full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2011;1993, publisher: The Lilliput Press, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Dead as Doornails

- Author:

- Publisher:The Lilliput Press

- Genre:

- Year:2011;1993

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Dead as Doornails: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Dead as Doornails" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Dead as Doornails — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Dead as Doornails" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

for Bob and Sheila Bradshaw

Although this is a narrative, it is not an autobiography, except in so far as all the seven men remembered in it played some part in my li&e and are seen through my eyes. There is no signijcance in the number ckosen, outside the fact that they are all dead; they all died within a short space oftime ofeach other; all of them were acquainted with some of the others; and I was acquainted with them all.

AC

M Y SUBJECT is not myself and my doings, but it is never any harm to establish a little circumstance. In 1948 I had ceased to be a student and had become, for some reason, a barrister-at-law. It was a state in which I took no pride; indeed I was acutely ashamed of it for a number of reasons, some of them ideological and connected with whatever amalgam of anarchism and utopian communism I luxuriated in at the time, some to do with the fact that I was a poet, in so far as I was anything that could be named, and thought the barristership consorted ill with the practice of the art and the necessary dooms that attached to the calling. I was too ignorant to know that Beaumont and Fletcher, Browne of Tavistock, John Donne, Patrick Pearse, William Cowper, W.S. Gilbert, Sir Walter Scott and Robert Louis Stevenson, among others, had been in the same boat.

But in any case the company and general demeanour of my contemporaries who were now repairing to the Bar library, that peculiar communal place of business in the Four Courts, did not appeal to me. Among them I experienced what I think is probably a not uncommon mixture of feelings: superiority and inferiority at the same time, the latter for certain social reasons, ludicrous in the retrospect and impossible now to define, and by this time I felt, and I dare say looked, an oddity. Besides, I had never had any intention of practising the profession, though since I have never been any good at long-term decisions, nor very much aware of what I really want beyond certain fundamentals, I had never thought about the matter very clearly. Drift had, up to now, been the order of the day.

So I got a job ideologically of course as indefensible as the practice of law in the offices of an association of retail traders, bluffing my way through a large field of candidates with the aid of the barristership and some borrowed clothes, the only use the former had ever been to me, if it was a use. The job was supposed to be a bit of a prize other members of the senior branch of the legal profession had applied. But then, hard times were in it all round. The facts were that I earned seven pounds three shillings a week, paid three pounds for digs and drank the rest. The borrowed clothes had been returned. My own were in no sort of shape. I was no good at the job. I was not happy and I knew it.

My personal inadequacies and griefs were many. There was my relationship with my parents and theirs with the onset of age; my non-existent sex life, perhaps really an improvement over student dating and courting, though that was not how I saw the lack; my sufferings in the office. But anyway Dublin in the late nineteen-forties was an odd and, in many respects, unhappy place. The malaise that seems to have affected everywhere in the aftermath of war took strange forms there, perhaps for the reason that the war itself had been a sort of ghastly unreality. Neutrality had left a wound, set up complexes in many, including myself, which the post-war did little to cure.

Nor were there then concourses of young poets to associate with, such as exist to keep each other company today. Most of the elder ones, known to local fame, were respectable Gaelic revivalists , in orthodox employment in the civil service or the radio station . Left becalmed in the wake of genius, they sat, it seemed, nightly in the Pearl or the Palace, comforting themselves with large whiskeys, reminiscences of F.R. Higgins and discussions of assonance , before going home to the suburbs. One recognized their life-style as the viedelettres locally accepted and approved. It was not somehow attractive, nor probably attainable, but of course one felt the lack of confrres. Except for one or two who had been student poets along with me, and were now busy bracing themselves for the serious business of getting on in the world, I had none. I disliked, as I say, my childish, snobbish, bar contemporaries. I knew no girls; could not be bothered to go through the motions necessary to pick one sort up in dancehalls, nor make the arrangements involved in taking another to the middle-class dress and supper dances in the Gresham and the Metropole which appeared to provide my contemporaries with a large part of their social and, such as it was, their sex life. What I needed, I obscurely felt, was a bohemia of some kind, but I did not know where to find one.

Then things suddenly took a turn for the better. I got thrown out of digs and met an acquaintance to whom I explained my problem , which was really that I could not afford ordinary digs and do my drinking at the same time. He told me he knew about a place where I might get to stay pretty cheaply and told me the name of the pub where I might find the owner. The pub was McDaids; and the place was the since-famous Catacombs. I did not know it then, but my feet had been happily set upon the downward path, and there was to be no looking back.

McDaids is in Harry Street, off Grafton Street, Dublins main boulevard of chance and converse. It has an extraordinarily high ceiling and high, almost Gothic, windows in the front wall, with stained glass borders. The general effect is church-like or tomb-like, according to mood: indeed indigenous folklore has it that it once was a meeting-house for a resurrection sect who liked high ceilings in their places of resort because the best thing of all would be for the end of the world to come during religious service and in that case you would need room to get up steam.

The type of customer who awaited the resurrection and the life to come has varied a little over the years, but in spite of rather weak-minded attempts to make it so, McDaids was never merely a literary pub. Its strength was always in variety, of talent, class, caste and estate. The divisions between writer and non-writer, bohemian and artist, informer and revolutionary, male and female, were never rigorously enforced; and nearly everybody, gurriers included, was ready for elevation, to Parnassus, the scaffold or wherever.

At the time of which I speak the company was very various. There were a number of painters and sculptors, few of them serious , fewer to last. There were some Americans, ex-servicemen who had come to Ireland originally to be Trinity students under the G.I. Bill and remained on when its bounty was exhausted, among them J.P. Donleavy, then supposed to be a painter but meditating a big book about Ireland to be called, I seem to remember, Under the Stone; and Gainor Crist, who was to provide the original for that book, subsequently TheGingerMan (a curiously transformed and lessened portrait), and to die, in appalling circumstances, in the Canary Islands in the early sixties.

Originally perhaps because of the association of Desmond MacNamara, a sculptor who had a studio nearby, with the late Pope OMahoney and the Republican Prisoners Aid Fund, there were numbers of former prisoners, variously in need of aid of diverse kinds (some of it highly unorthodox) and fairly recently released from various gaols and internment camps in Britain and Ireland. In fact if the prevailing atmosphere in McDaids at this time could have been described, bohemian-revolutionary might have been the phrase. Eddie Connell, who had been, in I.R.A. parlance, Officer Commanding Parkhurst, Isle of Wight, and Peter Walsh, who had similarly commanded the I.R.A. prisoners in Dartmoor, were prominent; but there were many others, chiefly ex-internees from the Irish governments camp at the Curragh; and, to go with them, in case there were any lingering vestiges of activism about, there were a few special-branch men, or reputed special-branch men. Not many of the I.R.A. had orthodox, or indeed any, employment, no more than had the sprinkling of latter-day anarchists, communists etc. who had followed them in, or the bohemian rentiers, many of them English or very Anglo-Irish, who rejoiced in the general atmosphere. There were also a few girls, some of whom had employment as wives, mistresses or otherwise, some not.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Dead as Doornails»

Look at similar books to Dead as Doornails. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Dead as Doornails and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.