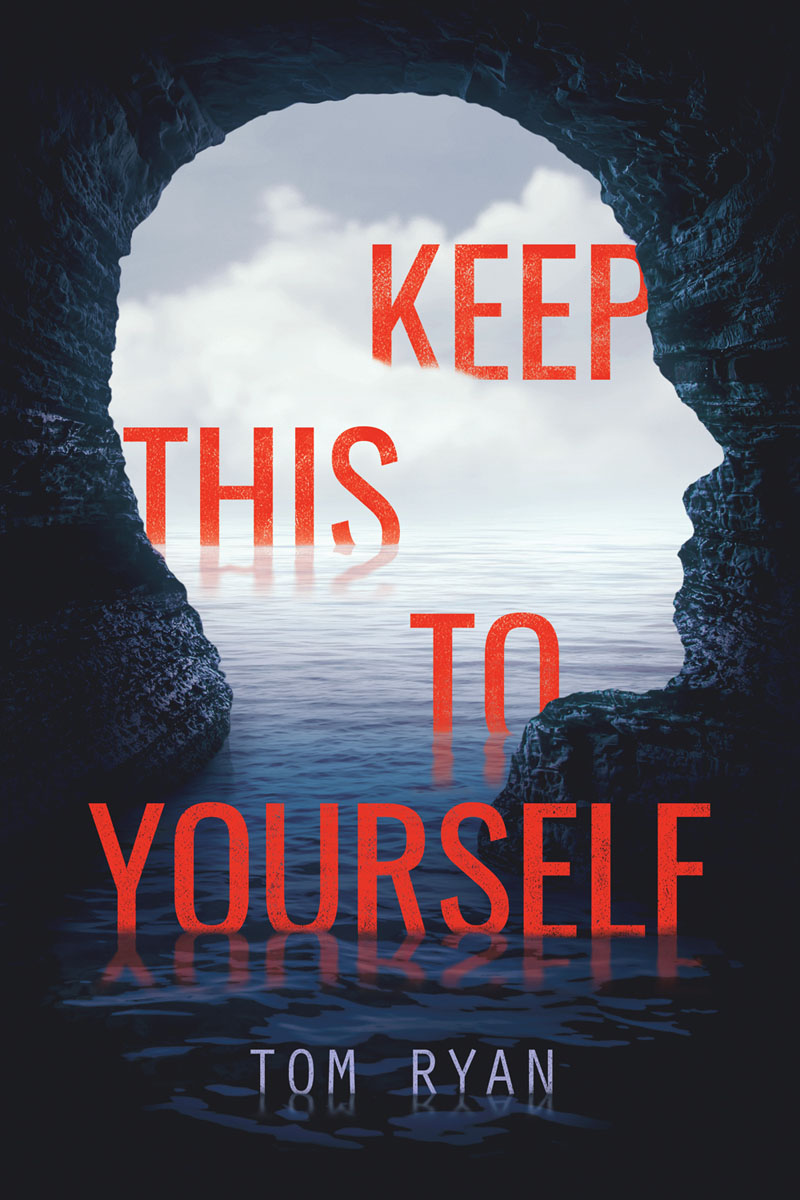

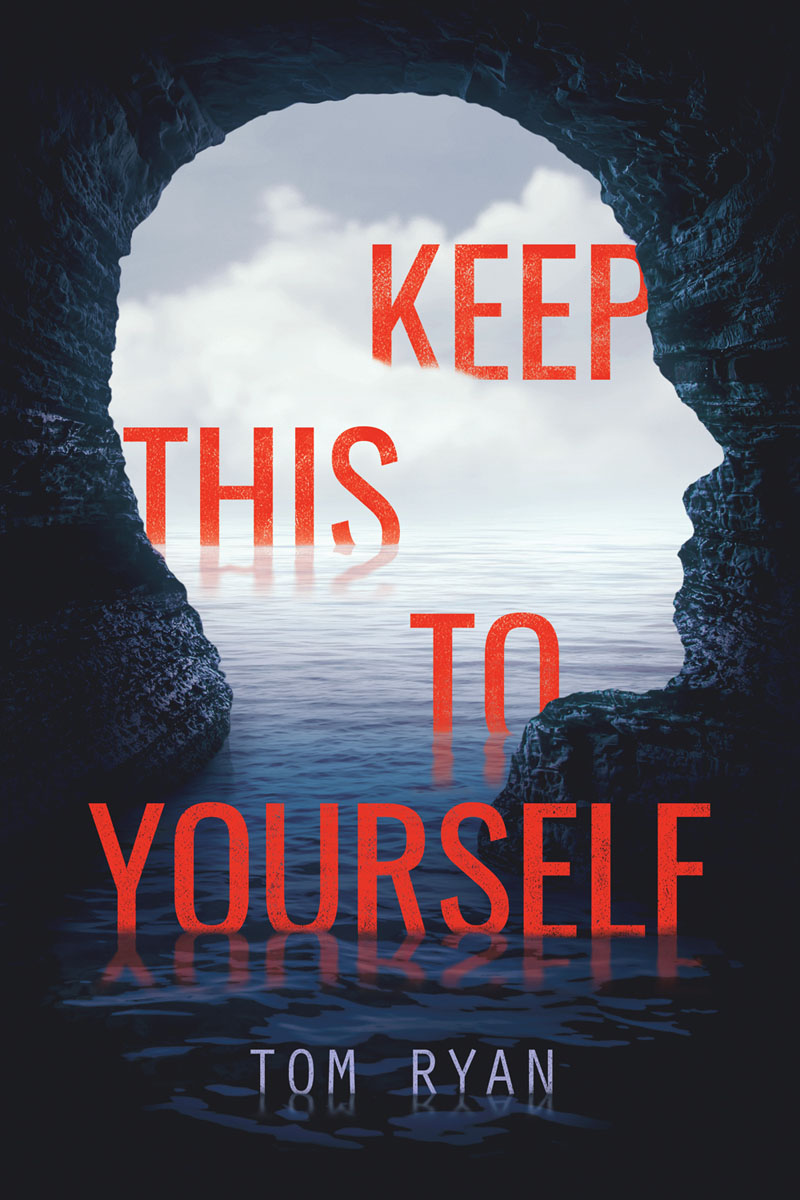

TOM RYAN is the author of several books for young readers. He is a two-time Junior Library Guild selectee, two of his novels have been chosen for the ALA Rainbow List, and he is a 2017 Lambda Literary Fellow in young adult literature. Tom and his husband currently split their time between Ontario and Nova Scotia. For more information, visit www.tomryanauthor.com .

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data is on file with the publisher.

Text copyright 2019 by Tom Ryan

First published in the United States of America in 2019 by Albert Whitman & Company

ISBN 978-0-8075-4151-7

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 BP 24 23 22 21 20 19

Cover images copyright by Noel/Adobe Stock, eugenesergeev/iStock, Artem Bali/Unsplash Design by Aphee Messer

For more information about Albert Whitman & Company, visit our website at www.albertwhitman.com.

100 Years of Albert Whitman & Company

Celebrate with us in 2019!

For Andrew.

How did I get so lucky?

ONE

TO BE HONEST , Im not sure I was expecting anyone to show up, but when I come to the end of the overgrown path, pushing through a tangle of bayberry and wild roses into the clearing, Ben is already there.

Hes still dressed in his graduation clothes: khakis and a button-down, his tie undone so that it hangs limp around his neck like a rope. His bike has been tossed onto the grass, and hes hoisted himself up onto one of the granite ledges that shelters the space, dangling his feet off the side. He raises a hand as I approach.

Hey.

Hey. I smile, trying to act normal, as if we still hang out here every day. As if we hang out at all, anymore.

You managed to get away, he observes.

Finally, I say. My parents dragged me out to dinner with my grandparents. I thought it would never end.

He lets out a half laugh, one dead syllable that drops straight to the ground.

My parents cant even be in the same room together, Ben says. They started arguing in the school parking lot over who would get to take me out to eat, so I slipped away and came here instead.

Youve been here that long? I ask, surprised. Its been over two hours since our graduation ceremony ended.

He shrugs. I like it here. Its nice.

I scramble awkwardly up onto the ledge to sit next to him, and we stare out at the water. Hes rightit is nice. Its a beautiful June evening, still bright, although the sun is starting to drop toward a bank of thick clouds painted on the horizon.

From up here on the bluff we have a perfect birds-eye view of Camera Cove: rows of brightly painted wooden houses; the commercial district, with its quaint shops and restaurants; the town halls elegant brick clock tower; the boardwalk twisting along the stretch of sandy beach to the jagged, cave-riddled cliffs at its far end.

From a distance, you would never think that there was anything more to the town than the postcard prettiness thats always been its claim to fame; was its only claim to fame, before last summer.

Hello, boys.

We both turn at the sound of the voice. Doris has materialized at the base of the path, as if from thin air. Shes the kind of person who looks exactly the same now as she did when she was a little kid, and probably still will when shes eighty. Pin-straight, shoulder-length black hair, bangs sharp enough to slice your finger, tortoise framed glasses, wide strapped canvas shoulder bag. Every piece of clothing is perfectly clean and neat and pressed, every hair in place.

Congratulations. Or should I say, congraduations? she says, in a pretty accurate impression of Anna Silvers perky valedictory speech. Jesus, that was tough to get through. I was dying for a Xanax.

Something else that will never change about Doris: her sarcasm. She might be neat and tidy on the outside, but inside shes all barbs and sharp edges. Ive known her since we were kids, but shes a tough nut to crack.

It wasnt that bad, says Ben. I thought she did an okay job.

Are you kidding me? She actually used the phrase now its time to spread our wings. I thought she was going to break into song.

I dont say anything. Annas speech might have been a bit chipper, but it would have been a hard job for anyone this year, under the circumstances.

No family party for you? I ask instead.

Doris rolls her eyes. Fat chance of that. Im surprised my parents even showed up at the ceremony. She points at the sun as it begins to dip behind the clouds. Looks like Im just in time. Lets get this show on the road.

We all turn to look at the ancient, gnarled oak, the only tree on this windswept bluff.

Do you think we should wait for Carrie? asks Ben.

I was sure shed be here, I say, which isnt really true. I wanted her to be here. The Carrie I grew up with wouldnt have missed it, but Ive barely spoken to her since last summer.

He shrugs. Maybe shell still show. Its kind of important.

Important, scoffs Doris. Give me a break. Carries not coming, guys. Shes done a better job of forgetting things than the rest of us.

If it isnt important, why are you here? Ben asks her, with an uncharacteristic flash of irritation.

I look back and forth between them as they bicker, vaguely aware that the sun has disappeared behind the clouds and the light has shifted. They look distant to me, as if Im watching characters in a movie, rather than people who used to be my best friends.

It seemed like a good way to wrap things up, says Doris. Im ready for this year to be over. Im sick of thinking about it. Im sick of knowing that everyone else is thinking about it. Im ready to start thinking about something else.

You make it sound easy, he says.

No, its not easy, Ben, and now Doris is the one who sounds irritated. But its necessary, so lets have our little ceremony or whatever and start getting the hell over it.

She walks over to the oak tree and crouches at the base, and Ben and I follow her.

Why did you come, Mac? Ben asks me as we kneel down beside her.

Because we made a promise, I say.

They glance at each other. Its a quick, instinctive thing, almost imperceptible, but I notice it. It occurs to me for the first time that they might only be here for my benefit. Because they feel sorry for me, their weird friend.

Even though were not friends. Not really. Not after last summer.

The three of us stare into the thick claw of roots at the base of the tree, muscular and knotted. Its easy to imagine them continuing down in a death grip beneath the surface. In front of us is a hollow, packed tight with rich, dark earth.

How are we going to do this? I ask. I wasnt really thinking. I could run home and get a shovel or something.

But Doris has already unslung her bag and opened it in front of us. She pulls out a large Ziploc bag. Inside, cocooned like police evidence, is a gardeners trowel, caked with dirt.

Its my mothers, she explains. She opens the bag and pulls out the trowel, then twists it forward into the hollow and starts to dig awkwardly.

Next page