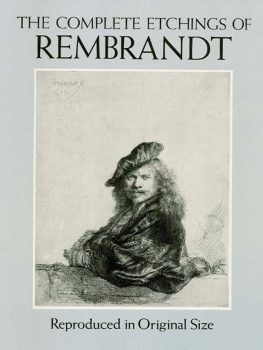

THE REMBRANDT SECRET

ALEX CONNOR is also known as Alexandra Connor and she has written a number of historical novels. This is her first crime thriller. She is an artist, and has worked in the art world for many years. Alex is also a motivational speaker and is regularly featured on television and BBC radio. She lives in East Sussex.

THE REMBRANDT SECRET

Alex Connor

F or my father

First published in Great Britain in 2011 by

Quercus

21 Bloomsbury Square

London

WC1A 2NS

Copyright 2011 by Alex Connor

The moral right of Alex Connor to be

identified as the author of this work has been

asserted in accordance with the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication

may be reproduced or transmitted in any form

or by any means, electronic or mechanical,

including photocopy, recording, or any

information storage and retrieval system,

without permission in writing from the publisher.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84916 346 0

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters,

businesses, organizations, places and events are

either the product of the authors imagination

or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to

actual persons, living or dead, events or

locales is entirely coincidental.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Typeset by Ellipsis Books Limited, Glasgow

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives Plc.

A man who seeks revenge should first dig two graves.

Confucius

BOOK ONE

Prologue

House of Corrections,

Gouda, 1651

This is the story of me.

I am writing it because one day someone will read it and know the truth. I write it believing that my history will get out of this place, because I never will. They have locked me in here, slammed the door on me. And when I panicked, water was thrown on me. It dried cold, the white cap which covered my hair stiff with starch, and spittle from one of the guards. After he had tried to feel under my skirt. After they searched me, looking in my mouth and ears, and in my private parts, forcing fingers into orifices, making an animal out of me.

They take your life away from you when they lock the door. When they say Geertje Dircx, housekeeper to Rembrandt van Rijn, has been committed to an asylum. She is a nuisance, she abused her employer verbally, accused him of breach of promise, sold the ring he gave her: the ring which once belonged to his late wife. She is immoral, she is ungrateful, she is mad with bitterness and anger, telling lies, spreading gossip about how her master had promised he would marry her.

But she is silent now.

Only these pieces of paper hear my history I lay with him when I had been at the house for some few weeks. He was grieving for his dead wife and I was eager to be promoted from kitchen to bed chamber, lying next to him and dreaming that the child I had been hired to take care of might one day become my stepson. Sssh I hide these papers when I hear a noise. A footfall on the corridor outside means guards and people who peer in on me, watching me even when I relieve myself. Watching me, because I am labelled now. Locked up in the House of Corrections as a woman of licentious habits. A danger to myself, they said, when they took his part which I should have known they would. Powerful and respected, how simple was it for him to have one mistress put aside for the newcomer. A girl younger than myself, with plump, country flesh that he will explore and probe. And then he will paint her. As he painted me.

She will look after him and his son, and sweep the floor, with its monochrome tiles, when the sunlight comes through the stained glass of the windows and makes fireflies on the panelling. She will smell the linseed oil and rabbit glue, and know the sound of the pestle grinding the colours with the oils and turpentine which burn the back of her throat. I know she will creep upstairs and watch his pupils work, and watch him too. She will rummage amongst the heaps of costumes and props he collects for his paintings and hang back in the shadows when patrons come to the studio. She will find herself glancing at her reflection in the mirror a little longer than she used to, counting her attractions, because she wants the image to please him. She will do all this because I did. And I watched him watch me, and watched his expression turn from affection to love. I watched it let no one say otherwise.

Sssh I am pausing now, hiding the paper under the skirt of my dress as someones eyes scrutinise me through the peevish little hatch in the door. I perform a crude gesture and the guard walks away, making a sucking sound with his lips. They think Im promiscuous. I was once, with a few men, in the tavern where I worked, after I was widowed. I was, once. But they gave false evidence against me later. Not just my neighbours, but my own brother What was he paid to lie? What amount was enough to have his sister committed? Does he lie awake in Amsterdam and look out of his free window at his free moon and wonder what sliver of captive sky his sister catches through the bars ?

I could have ruined van Rijn then, but I stayed silent. Could have exposed a secret which would have hobbled him and got all Holland grinding him under the heel of their righteous Dutch boot. But I stayed silent. Only asked for what he promised, what he later denied me Its getting dark now, I can hardly see to write anymore. But tomorrow Ill continue. My history will be told and I will destroy you, van Rijn. From the asylum where you put me, out of your bed and your life, from here, on scraps of hidden paper, I will chart your ruin.

I shall write these letters to myself. I shall keep my sanity by this record. And one day, when they are read, the world will know you. They will know me, and you and Rembrandts monkey.

Amsterdam

His body was bent over, his head submerged in the confines of the basin, his knees buckled, trousers pulled down. Blood seeped from between his buttocks, intensive bruising around the top of his fleshy thighs. On the floor beside his puffy right knee lay the toilet brush, its handle bloodied. A series of small nicks covered his lower back and the skin of his scrotum was mottled with burn marks. Although his head was submerged, the back of his neck showed the imprint of fingers; his wrists bound together with the same gilt wire often used to hang paintings.

It had taken him a long time to die. As he fought, he had struggled, his wrists jerking against the wire as it cut deep into his flesh, down to the wrist bone in places. Repeatedly his head had been dipped into the filled basin, then pulled out, then submerged again. When the water finally began to enter his lungs, his body had reacted, foam spittle gathering at the corners of his mouth. Much later it would rise from the corpse to make a white death froth. Against the push of water, his eyes had widened, the pupils turning from clear orbs to opal discs as he stared blindly at the bottom of the basin.

The killer had made sure that the death of Stefan van der Helde would horrify not only the people who found him, but also his business associates and his cohorts. In sodomising him they had exposed Van der Heldes hidden homosexuality, humiliating him and bringing down one of the top players in the art world. But there was more to it than that: a reason why no one would ever forget the death of Stefan van der Helde. When his body underwent post-mortem examination the pathologist found stones in his stomach. Apparently, over a period of hours, he had been forced to swallow pebbles, one after the other, each one larger than the last, until they threatened to choke him. Even when his oesophagus reacted and went into spasm, he was forced to keep swallowing, his gullet bruised and torn in places by the stones.

Next page