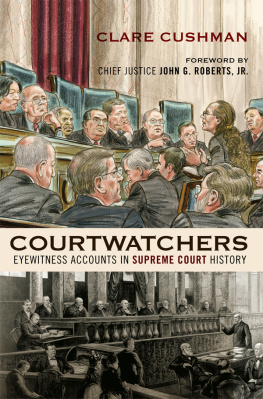

Courtwatchers

Courtwatchers

Eyewitness Accounts in Supreme Court History

Clare Cushman

Published in Association with the Supreme Court Historical Society

Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Lanham Boulder New York Toronto Plymouth, UK

Published in association with the Supreme Court Historical Society

Published by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

http://www.rowmanlittlefield.com

Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom

Copyright 2011 by Supreme Court Historical Society

The copyright page is continued in the acknowledgments section.

All rights reserved . No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Cushman, Clare.

Courtwatchers : eyewitness accounts in Supreme Court History/ Clare Cushman.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-4422-1245-9 (hardback) ISBN 978-1-4422-1247-3 (electronic)

1. United States. Supreme CourtHistory. 2. United States. Supreme CourtOfficials and employeesSelection and appointmentHistory. 3. JudgesUnited StatesHistory. 4. Judicial processUnited StatesHistory. 5. Clerks of courtUnited StatesHistory. I. Title.

KF8742.C875 2011

347.73'2609dc23

2011019794

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

Printed in the United States of America

To my husband and children, without whom I would have finished this book much sooner.

Foreword

Each year, hundreds of thousands of Americans visit the Supreme Court of the United States. They are justly proud of this great institution, yet most are struck by the anonymity of the seventeen Chief Justices and one hundred Associate Justices who have served on the Court over the past two centuries. Some of the portraits that line the Courts halls are readily recognizable: Oliver Wendell Holmes is sternly majestic; Hugo Black is captured in radiant color; while Felix Frankfurter appears in a modernistic pastel sketch. But even history buffs steeped in the lore of the Court are likely to be stumped by the names beneath some of the other portraits. Just who are these people?

Clare Cushmans latest work, Courtwatchers , helps to answer this question. She has written an informative survey, drawn from firsthand accounts, that brings the Justices to life. Drawing on recollections and recorded observations from a wide sweep of sources, the book provides what a good anecdote conveysthe sense of personality. Ms. Cushman has organized her book around topics that capture the human element of the jurists. She places them in the context of their times by examining the Courts early history and forgotten hardships, like circuit riding. She explores both the process of becoming a judgeincluding appointment, confirmation, and learning the ropesand the poignant process of stepping down from the Court. But she also sets aside the black robes and delves into the private side of life on the Court, capturing vignettes of relations among friends, family, and one another.

Art critics tell us that good portraiture engages the viewer in two dimensions by commingling the subjects objective appearance with the artists subjective impressions. Ms. Cushmans collection of firsthand observationsmany of which, by virtue of resting on recollection, are open to historical debateadd depth to the Court in both those dimensions. Her book will delight all those who want to look beyond the portraits and gain an intimate view of the individuals who have quietly contributed so much to the work of the Court and the advancement of justice.

Chief Justice John G. Roberts, Jr.

Introduction

In the early nineteenth century, the Supreme Court sessions were considered the best show in town. One now-forgotten case argued over the span of ten days by an all-star lineup of orators, including the thrilling Daniel Webster, drew overflow crowds in 1844. A spectator reported:

Daniel Webster is speaking.... There is a tremendous squeeze, you can scarcely get a case knife in edgeways.... Hundreds and hundreds went away, unable to obtain admittance. There never were so many persons in the Court-room since it was built. Over 200 ladies were there; crowded, squeezed and almost jammed in that little room; in front of the Judges and behind the Judges; in front of Mr. Webster and behind him and on each side of him were rows and rows of beautiful women dressed to the highest. Senators, Members of the House, Whigs and Locos, foreign Ministers, Cabinet officers, old and youngall kinds of people were there. Both the Presidents sons, with a cluster of handsome girls, were present.... The body of the room, the sides, the aisles, the entrances, all were blocked up with people. And it was curious to see on the bench a row of beautiful women, seated and filling up the spaces between the chairs of the Judges, so as to look like a second and a female Bench of beautiful Judges.

During a more routine day in the Supreme Court, the same reporter compared the scene to a ballroom, musing that if old English judges were to witness the sight, each particular whalebone in their wigs would stand on end at this mixture of men and women, law and politeness, ogling and flirtation, bowing and curtseying, going on in the highest tribunal in America.

Watching a Supreme Court session today is still awe-inspiring. The line of would-be Courtwatchers waiting to take their turns in the seats reserved for the general public can often stretch down the steep white steps of the Marble Palace. The Supreme Court does, however, operate in a less theatrical manner than it did in 1844. It is definitely not a place to flirt.

Indeed, if Webster were to visit todays majestic Courtroom in session, he would be startled to see that women are no longer decorative spectators. One-third of the Justices occupying the bench are female, and the attorney standing at the podium may well be too. Webster would also be surprised that instead of enjoying the leisurely pace of oral argument that characterized his erawith no time restrictions and orators declaiming flowery rhetoric for days on endadvocates are now permitted only half an hour to make their case. And instead of listening deferentially, the Justices barrage them with questions, trying to get to the crux of the legal issues as quickly as possible.

Webster would probably be equally dismayed to watch oral arguments end abruptly, with the Chief Justice unceremoniously stopping counsel from going beyond the allotted time, even to wrap up a point. A current member of the Supreme Court bar, with more than twenty oral arguments under her belt, Maureen Mahoney has described the contemporary experience of being cut off in mid-sentencesomething Webster and his peers at the Supreme Court bar did not even begin to contemplate until 1849, when time limits for each side began to be imposed. A former clerk to Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist, Mahoney was granted no special consideration in the Courtroom by her mentor, a strict stickler for time limits:

The way the light system works in the courtroom is that it will tell you, when a light goes on, that you have five minutes remaining, and when your time is expired a red light goes on. In the Supreme Court, when the red light goes on, you are supposed to stop. When Chief Justice Rehnquist was presiding, you were really supposed to stop. I remember one time where Justice [Antonin] Scalia had asked me a question, and the red light went on just as he was finishing his question. I hadnt had a chance to say a word. I looked up at the Chief Justice, and he said Counsel, I think you can consider that a rhetorical question. And so I just sat down. In fact, the press didnt know that the red light was on, so they reported that I was speechless in response to Justice Scalias question.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.