Copyright 2013 by Arizona Community Foundation

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

RANDOM HOUSE and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

OConnor, Sandra Day.

Out of order: stories from the history of the Supreme Court / Sandra Day OConnor.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

eISBN: 978-0-8129-9393-6

1. United States. Supreme CourtHistory. 2. United States. Supreme CourtAnecdotes. 3. Courts of last resortUnited StatesHistory. 4. Courts of last resortUnited StatesAnecdotes. I. Title. KF8742.O276 2013 347.732609dc23 2012025708

www.atrandom.com

246897531

Cover design: Anna Bauer

Cover illustrations: Peter Gridley/Getty Images (columns);

Harris & Ewing/Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States (Oliver Wendell Holmes);

Associated Press (Ronald Reagan and Sandra Day OConnor)

v3.1

CONTENTS

LOOMING LARGE

Historic Intersections of the President and the Supreme Court

THE CALL TO SERVE

Judicial Appointments

A HOUSE IS NOT A HOME

The Journey to One First Street

HUMBLE BEGINNINGS

The First Decade of the United States Supreme Court

ITINERANT JUSTICE

Riding Circuit

GOLDEN TONGUES

Oral Advocacy Before the Court

GONE BUT NOT FORGOTTEN

Judicial Retirement

APPENDIX A

The Declaration of Independence of the United States of America

APPENDIX B

The Constitution of the United States

INTRODUCTION

O N S EPTEMBER 25, 1981, MY FIRST DAY AS A U NITED S TATES Supreme Court Justice, I walked up the steps to the Supreme Court for only the second time. Decades before, I had visited the Court with my husband, John, as a simple tourist while John was attending army training in neighboring Virginia. It was a Saturday and the Court was closed. I snapped a picture of John as he stood on the marble steps. I remember thinking that that was the closest I would ever get to the Supreme Court. I could not have fathomed that, years later, I would walk down those marble steps as a member of the Supreme Court and serve for nearly twenty-five years.

The Supreme Court Building is an awe-inspiring sight. Many a visitor each year is stopped in his or her tracks by the grandeur and solemnity of the white marble staircase and the soaring inscription on the Courts faade, EQUAL JUSTICE UNDER LAW . An inspiring and profound image of permanence and continuity, the Court stands as a symbol of our commitment as a society to the rule of law. It stands for our Founding Fathers uniquely American vision of an independent judiciary, in which judges and the Court would stand alone, independent and not beholden to the will of political majorities in their interpretation of the laws and the Constitution.

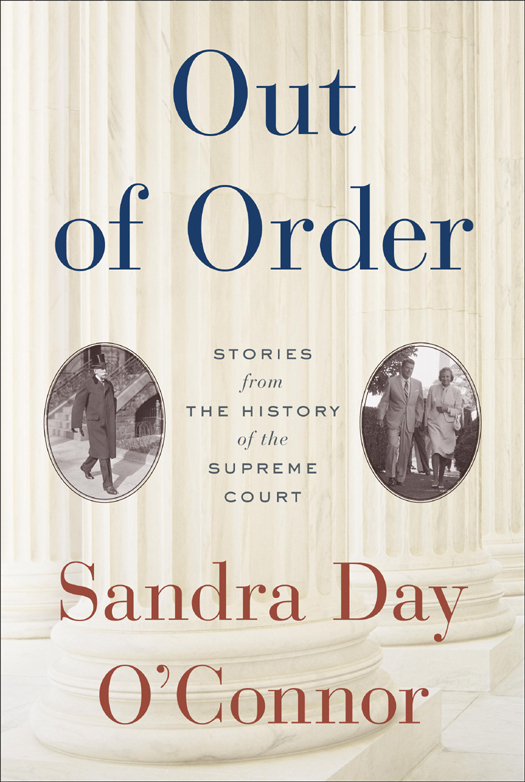

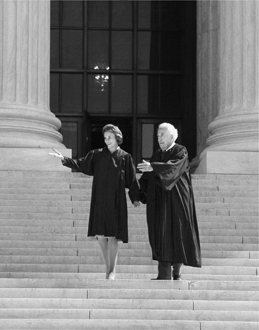

Chief Justice Warren Burger escorts Justice Sandra Day OConnor down the front steps of the Supreme Court on the day of her investiture. ()

Most people would say that the reasons for having the legislative and executive branches of government are obvious. After all, we need legislators to make the laws, and an executive to enforce And while memories of King George IIIs tyrannical reign fostered distrust of executive power, the Framers also recognized the need for a vigorous presidency rooted in the will of the people. Under the Articles of Confederation, a weak national government had struggled to provide for the countrys needs and speak for the people with a single voice.

But why did the Framers envision for the new government a judicial branch whose members, unlike those of the legislative and executive branches, would be unelected? And why was a federal judiciary necessary, given the extensive system of state courts in existence at the time of the Founding? Today, state courts can still decide nearly any issue of law and they still handle the bulk of the nations cases.

The Framers wished to create an independent federal judiciary because they knew that the new national political branches could not be left unchecked. Our congressmen and President serve as elected representatives. In that role, they are supposed to speak for and answer to the people. For that reason, the Framers did not rely on the political branches to protect minority groups with less popular, more marginal interests. And so they assigned federal courts primary responsibility in guarding against the overreaching and excesses of the political branches, recognizing the benefits of a judiciary that functions as an outsider to the system of majority will.

The majestic building on One First Street in our nations capital stands as a monument to our Founding Fathers vision. Erected across the street from the Capitol, and across town from the White House, the building stands as a physical testament to the Courts status as an independent, coequal branch of government. The Supreme Court today regularly reviews the legality of laws passed by Congress and enforced by the executive branch. And from time to time, the Justices find themselves compelled by the law to strike down invalid government action by the political branches. The Courts decisions today, though often the subject of public criticism, are followed and adhered to even by those who disagree. Indeed, the Court has withstood tests of its authority on matters as controversial as school desegregation in the 1950s and the conduct of the War on Terror in the first decade of this century.

I had the privilege of serving on the Supreme Court from 1981 until 2006, as it confronted issues running the gamut from states rights and race-based affirmative action to a defendants right to effective assistance of counsel. My colleagues and I always strove to reach the right answers, and I hope that we did. We were able to resolve tough questions in an atmosphere insulated as far as possible from political pressures.

In those years, I also grew accustomed to many things that facilitate the important role that the Supreme Court plays in our system of government. For instance, it went without saying that, at any given time, I had eight colleagues who were well trained in the law, committed to their jobs, and willing to spend years, even decades, as officers of the Court. It also went without saying that the Term followed a regular schedule, that we had personal chambers in which we could work, and that we had available clerks and reporters offices that ran like well-oiled machines. The staff at the Court are first-rate professionals, and I had my pick of wonderful, talented law clerks to assist in my chambers each year.

This was not always the case. Far from it. So many aspects of the Court were shaped and developed little by little, year by year, person by person. The Court was a daring, bold, but risky political experiment, and its beginnings were modest and uncertain. In reflecting on the Courts humble early days, it is striking to note how dramatically the Court and its practices have evolved and how so much of that evolution was born of struggle and serendipity. I find it remarkable to reflect on how, for many decades of the Courts early existence, so much of what we take for granted was steeped in uncertainty. The many Justices who have come and gone have made contributionsdramatic and subtle, renowned and lesser knownto not only the law, but the institution and its internal operations.