Table of Contents

This book is dedicated

to my law clerkspast, present, and future

PRAISE FOR The MAJESTY of the LAW

With this important book, one of the most intriguing figures in American history reveals her private musings about history, the law, and her own lifeboth public and personal. The Majesty of the Law shows us why Sandra Day OConnor is so compelling as a human being and so vital as a public thinker.

MICHAEL BESCHLOSS, author of The Conquerors:

Roosevelt, Truman, and the Destruction of Hitlers Germany, 19411945

Justice OConnors newest book will intrigue and enlighten many different readers. She discusses multiple issues, including what its like to be on the Supreme Court, how and by whom the Court has been shaped, and the meaning of the rule of law. Her reflections on women in the law, and women in power, are especially thought-provoking. No one is better qualified than she to write about these issues, and she does so with her customary wit and clarity.

NAN KEOHANE, president, Duke University

A marvelous collection of wide-ranging and plainspoken ruminations on the Constitution, consitutionalism, and the Supreme Court by the Courts first female Justice. Justice OConnors keen-wittedness, honesty, and common sense are revealed throughout. Although she eloquently reveals the majesty of the law, she also brings that majesty down to earth and makes it intelligible to all of us. It is her special genius.

GORDON S. WOOD, Alva O. Way University Professor and

professor of history at Brown University, author of

The American Revolution: A History

In The Majesty of the Law, Justice Sandra Day OConnor has blended personal reflections with key professional insights to give us a richly textured account of the fascinating history, current status, and hopeful future of the rule of law. The fact that the author is destined to take her place among the most influential Justices to serve on the modern U.S. Supreme Court makes this important book all the more significant.

JAMES F. SIMON, Martin Professor of Law at New York School and

author of What Kind of Nation: Thomas Je ferson, John Marshall,

and the Epic Struggle to Create a United States

Preface

When my husband John and I packed up and moved from Arizona to Washington, D.C., in 1981 to begin my service on the nations Court, we looked forward to the many new experiencesboth professional and personalwe were sure to have: enjoying new and wonderful friends; meeting with Presidents, Vice Presidents, cabinet members, ambassadors, and other Justices and judges from around the world; travel to each of the fifty states and sometimes other countries for speeches or meetings; and, most important, I looked forward to the privilege of applying myself to work worth doing, addressing the toughest legal issues in our nation, helping shape the development and explanation of the principles of federal law required to resolve these issues.

I felt molded in large part by my life in the Southwest, where I had spent my earliest days on a cattle ranch in a dry and isolated part of the Arizona desert. My favorite author, Wallace Stegner, put it best when he said, There is something about living in big empty space, where people are few and distant, under a great sky that is alternately serene and furious, exposed to sun from four in the morning till nine at night, and to a wind that never seems to restthere is something about exposure to that big country that not only tells an individual how small he is, but steadily tells him who he is.1

This book is an attempt to speak about my exposure not only to the Arizona desert and sun but to the rest of our country as wellexposure to the richness of its history, to the Supreme Court and to some of its members, and to some of the legal issues I have confronted along the way.

When the Supreme Court sat on the bench again the first Monday of October 2001, it had its full complement of nine membersone appointed by President Ford (Justice John Paul Stevens), four by President Reagan (Chief Justice Rehnquist, myself, Justices Antonin Scalia and Anthony Kennedy), two by President Bush (Justices David Souter and Clarence Thomas), and two by President Clinton (Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer). The process of nominating a new Justice tends to receive a good deal of attention. In more than two hundred years, the Court has had only 108 Justices, which comes to about one appointment every two years. An appointment to the Court is, therefore, in terms of frequency, about half as special as a nomination to the presidencyand involves infinitely less public participation and releasing of balloons. Nonetheless, a Court appointment (which requires both nomination by the President and confirmation by the Senate) is an occasion for public interest, as we have been reminded graphically in the past twenty years.

The person making the nominationthe Presidentdoubtless pays special attention to these appointments. From the Presidents point of view, I suppose its a little like trying to rear children. The President only gets to control the process for a brief periodin choosing a particular nomineeand then the Justice, like an eighteen-year-old, is free to ignore the Presidents views. And Justices are usually walking around in their judicial chambers long after the President who appointed them has departed the Oval Office. Parenting and nominating Justices have both been common activities among Presidents: all of our Presidents except seven had children, and all except threeHarrison, Taylor, and Carternominated at least one Supreme Court Justice.2 Like fathers in an earlier day, the President makes the proposal and escorts the new Justice down the aisle in the marriage between the Justice and the Court, which, barring impeachment, lasts until death does them part.

As I suspect has been the case with most Justices, my nomination to the Court was a great surprise to the nation but an even greater surprise to me. My former colleague Justice Lewis Powell once said that being appointed to the Court was a little like being struck by lightning in both the suddenness and the improbability of the event.3 I certainly never expected to be on the Court. Rather, I looked forward to continuing my career as a state court judge, having served happily as a trial judge and then, with equal contentment, on the Arizona Court of Appeals, for whose members I had deep affection and great professional respect. I had anticipated that I would live the balance of my life in our adobe house in the desert, where John and I had many friends and a pleasant way of life, and where we expected our sons to settle.

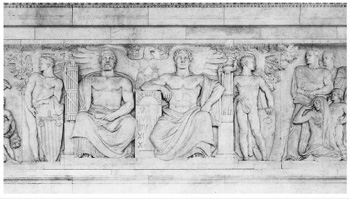

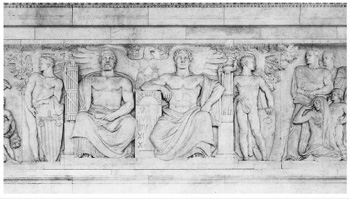

East courtroom frieze (Adolph Weinman, 19321934) in the Supreme Court building, titled TheMajesty of the Lawand the Power of theGovernment.

Next page