Published in 2020 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC

243 5th Avenue, Suite 136, New York, NY 10016

Copyright 2020 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC

First Edition

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwisewithout the prior permission of the copyright owner. Request for permission should be addressed to Permissions, Cavendish Square Publishing, 243 5th Avenue, Suite 136, New York, NY 10016. Tel (877) 980-4450; fax (877) 980-4454.

Website: cavendishsq.com

This publication represents the opinions and views of the author based on his or her personal experience, knowledge, and research. The information in this book serves as a general guide only. The author and publisher have used their best efforts in preparing this book and disclaim liability rising directly or indirectly from the use and application of this book.

All websites were available and accurate when this book was sent to press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

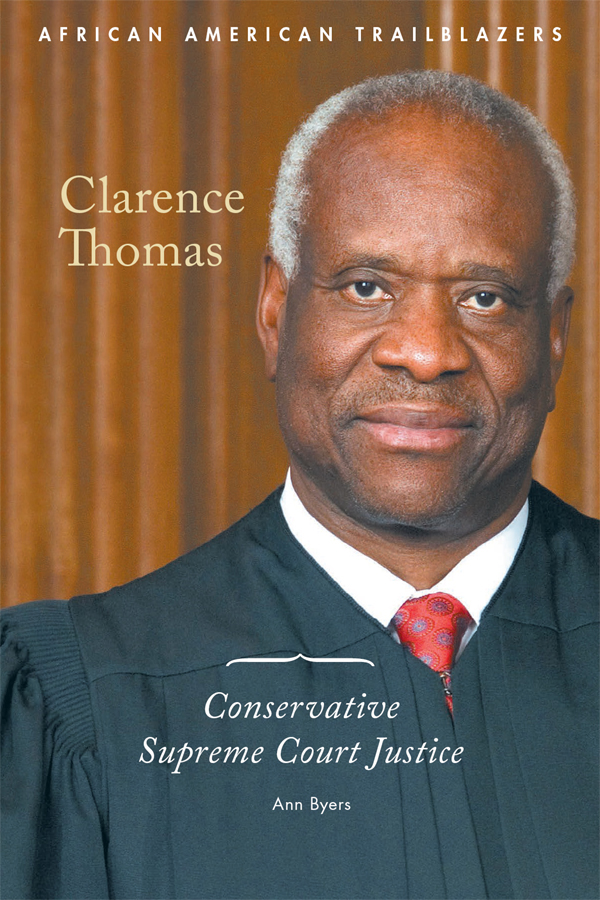

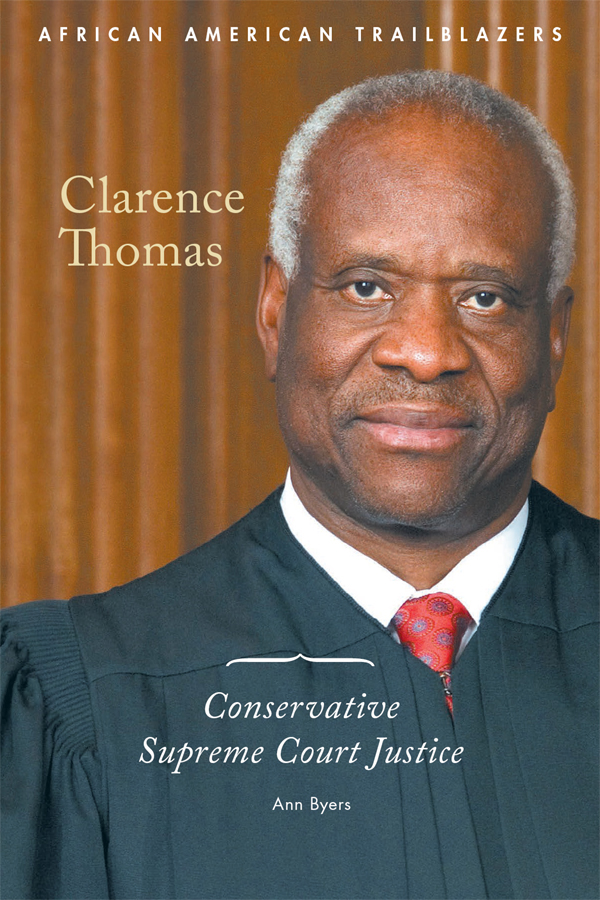

Names: Byers, Ann, author.

Title: Clarence Thomas : conservative Supreme Court justice / Ann Byers.

Description: New York : Cavendish Square, 2019. | Series: African American trailblazers | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018047207 (print) | LCCN 2018047965 (ebook) | ISBN 9781502645562 (ebook) | ISBN 9781502645555 (library bound) | ISBN 9781502645548 (pbk.)

Subjects: LCSH: Thomas, Clarence, 1948---Juvenile literature. | United States. Supreme Court--Officials and employees--Biography--Juvenile literature. | African American judges--Biography--Juvenile literature. | Judges--United States--Biography--Juvenile literature. | Political questions and judicial power--United States--Juvenile literature. Classification: LCC KF8745.T48 (ebook) | LCC KF8745.T48 B94 2019 (print) | DDC 347.73/2634 [B] --dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018047207

Editorial Director: David McNamara

Editor: Kristen Susienka

Copy Editor: Rebecca Rohan

Associate Art Director: Alan Sliwinski

Designer: Joseph Parenteau

Production Coordinator: Karol Szymczuk

Photo Research: J8 Media

The photographs in this book are used by permission and through the courtesy of: Cover The Collection of the Supreme Court of the United States/MCT/Getty Images; p. Joshua Roberts/Bloomberg/Getty Images.

Printed in the United States of America

CONTENTS

Associate Justice Byron White (far right) gives the constitutional oath to Clarence Thomas (left) at the White House in October 1991. George Bush (center rear), Barbara Bush (left of Thomas), and wife Virginia (right of Thomas) look on.

INTRODUCTION

Different

Times

O n October 15, 1991, the long, grueling hearings were finally over. The grilling, the cameras, the constant barrage of conflicting testimonyit all had come to an end. More than three months had passed since Clarence Thomas had been nominated to serve on the highest court in the United States, and they had been a blur of excitement, confusion, and profound discouragement. However, the ordeal was over. The Senate had voted to confirm him. Clarence Thomas was the newest associate justice of the United States Supreme Court.

Two Oaths

Within a few days of his confirmation, Thomas was sworn in twice. All federal judgesjudges for cases involving the United States government and its laws as well as disputes between statestake two oaths. The first is the Constitutional oath, the promise to uphold, protect, and defend the US Constitution. Thomas took this oath three days after his confirmation, standing next to President and Mrs. George H. W. Bush, with television cameras rolling. The second oath is the judicial oath. The judge vows to administer justice without respect to persons and to be fair and impartial to the poor and to the rich. Thomas recited this oath in a private ceremony five days later.1

In the week before the justices were to meet and his official duties would begin, Thomas paid a visit to the man he was replacing on the Supreme Court, Thurgood Marshall. It was simply a courtesy, a handoff of responsibilities from one man to his successor, a passing of the baton from one generation to the next.

Leaning on a Legacy

Thurgood Marshall and Thomas were alike in a number of respects. Marshall was the first African American to be appointed to the Supreme Court. Thomas, his successor, was only the second. Both were descendants of slaves, and both bore the scars of racial discrimination. They had both grown up in segregated neighborhoods, been educated in segregated schools, and been treated with derision because of their race. Both had risen above the prejudice to places of honor on the nations highest court.

However, the two men were dissimilar in even more ways. Marshall was an icon of the civil rights movement, personally responsible for many of its gains. In his four-year tenure as a judge on the US Court of Appeals, he handed down 112 rulings. He was appointed to the highest court by a Democratic president and confirmed by an impressive 60 to 11 vote of the Senate. Throughout his nearly sixty-year career as a lawyer and a judge, Marshall had gained a reputation as a very liberal champion of racial equality.

After the judicial oath, Thomas takes the traditional walk down the steps of the Supreme Court with Chief Justice William Rehnquist (left). He went directly to his first conference as associate justice.

By contrast, Thomas had been a judge for barely a year when nominated to the Supreme Court. He was appointed by a Republican president, edging through a contentious confirmation 52 to 48. As a steadfast conservative, he drew the criticism of many who feared his rulings might reverse some of the achievements of the civil rights movement.

Thomass courtesy visit to the outgoing justice grew into two and a half hours of lively conversation. When the subject of their differences came up, Marshall put them into perspective: I did in my time what I had to do. You have to do in your time what you have to do.2 In the years that followed, as Thomas wrestled with difficult cases, he would often take comfort in Marshalls words.

African American workers are photographed on the way to their jobs on a Mississippi cotton farm in 1937. The 6:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m. job paid a dollar a day.

CHAPTER ONE

The Legacy

of Slavery

T homass time was a century removed from the experience of slavery in the United States. Still, that experience cast a heavy shadow over his life and the lives of countless other African Americans. The system that was part of American life for nearly two hundred fifty years left deep scars on attitudes, actions, institutions, relationships, and laws. When Clarence Thomas was born in 1948, black people were barred from many public places. Blacks and whites lived in different neighborhoods, learned in separate schools, and sat apart from each other on trains and buses. The prejudices deeply rooted in slavery were evident everywhere, especially in the South.