Copyright 2021 by Jacqueline Calmes

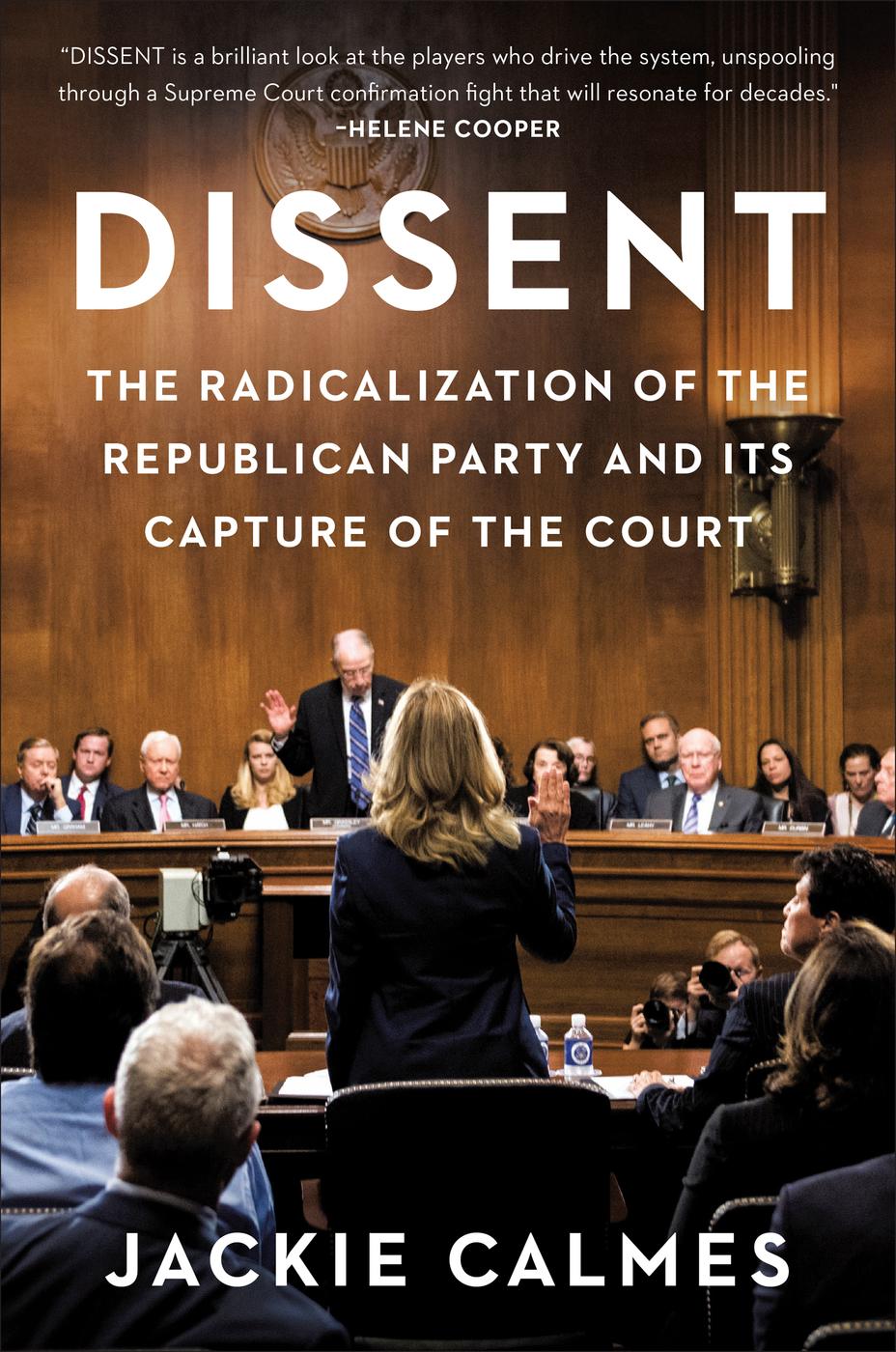

Cover design by Jarrod Taylor.

Cover photograph Tom Williams / Contributor / Getty Images.

Cover copyright 2021 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Twelve

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

twelvebooks.com

twitter.com/twelvebooks

First Edition: June 2021

Twelve is an imprint of Grand Central Publishing. The Twelve name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020948685

ISBNs: 978-1-5387-0079-2 (hardcover), 978-1-5387-0081-5 (ebook)

E3-20210505-DA-ORI

To my mother,

Jean Feehan Calmes Morgenstern (19332019),

and my youngest sibling,

Connie Calmes Szakovits (19662020).

Their memories are our blessing.

Explore book giveaways, sneak peeks, deals, and more.

Tap here to learn more.

A s my fortieth anniversary in journalism approached, Donald Trump had just been elected president. While his victory was a surprise, including to himself, he was no political aberration. Trumps rise in the Republican Party was the logical result of the partys ever-rightward, populist, and antigovernment evolution, a shift that coincided with my career in political journalism and was its single biggest story. Id been witness to that transformation from the midterm election year of 1978, when I arrived in West Texas for my first job at the Abilene Reporter-News, to Trumps election, by which time I was a Washington correspondent for the New York Times. Parallel to the Republican Partys gradual radicalization was the conservative movements long game to capture the Supreme Court.

At both the Times and, before that, the Wall Street Journal, one of the most frequent questions I had gotten from voters since the 1990s was some variation of Whats happened to the Republican Party? It was typically asked with disdain by Democrats and independents, and pain from current or former Republicans. All sides agreed that the party had moved so far to the right that it was on the wrong side of history on many issueswomens and LGBTQ rights, climate change, race, immigration, and moreand too uncompromising to govern effectively. I began thinking about a book addressing the voters question. By 2018, Id taken a job as White House editor for the Los Angeles Times, and as Brett Kavanaugh was poised for confirmation in October, my agent, Gail Ross, and editor, Sean Desmond, came back to me: What about telling the story of the Republican Partys modern transformation as the frame for Kavanaughs rise to become the justice who gave conservatives their long-sought lock on the highest court?

Their idea made sense, given Kavanaughs life experiences: coming of age in Reagans America, inside Washingtons Beltway; joining the infant Federalist Society at its founding campus, Yale; prosecuting Bill and Hillary Clinton; representing the Republican side in the partisan legal fights that bookended the 2000 election, first over custody of motherless Cuban refugee Elin Gonzlez and then in Bush v. Gore; advising George W. Bush through the polarizing years after 9/11; being rewarded with a federal judgeship, but only after a prolonged Senate confirmation fight emblematic of the eras partisan court battles.

I agreed to trace his path, through the years and political changes wed each seen from our respective vantages. It proved to be a challenging period in which to write the story, however. From Antonin Scalias death in 2016 through the aftermath of Ruth Bader Ginsburgs in 2020, Kavanaugh was just one of three arch-conservatives that Republicans forced onto the Supreme Court. In the process, it was roiled by the hyper-partisanship plaguing the U.S. government more broadly. The dynamic on the court shifted after Kavanaughs arrival and then again after Amy Coney Barretts. Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. first emerged as the controlling power at the center, and then, by late 2020, at key times found himself alone with the three liberals in dissent against the five right-wing justices. This upheaval created a headache for someone trying to write a book on the court. What was clear was that the court more than ever was showing the political divisions Roberts had been trying to avoid, and was poised to issue rulings outside the American mainstream.

In 1978, a year before Kavanaugh would enter Georgetown Preparatory high school in suburban Washington, I arrived for work in Abilene (home, incidentally, to his future wife, Ashley Estes, then just three years old; I took up jogging on the track at the high school shed attend). Texas had for more than a century been a near-solid Democratic state, except in presidential elections. That wild midterm year of Jimmy Carters presidency would mark the beginning of the national Republican Partys post-Watergate reemergence, heralding its ascendance in the Reagan years and the shift of its historic base from the North to the South. I was from two Democratic strongholds in the MidwestToledo, Ohio, where I grew up, and Cook County, Illinois, where I finished college. Texas back then was a Democratic bastion of a different sort. Many Democrats I met were more conservative than Republicans Id known. They often opposed the national party, yet remained yellow dog Democrats in state and local electionsso loyal, the saying went, that theyd vote for a yellow dog over a Republican. Texas was a two-party state, my translators joked: conservative Democrats and liberal Democrats, just like elsewhere in the South.

That November, my election-night story included the report of young George W. Bushs defeat for a House seat representing a district west of Abilene, including Midland and Odessa. His loss was expected, yet he did surprisingly well. So did other Republicans across the South, foretelling the wave Reagan would ride two years later. Texans in 1978 elected the first Republican governor since Reconstruction: Bill Clements, a rich and bombastic oilman, a sort of precursor of Trump. Among the Democrats who won, taking congressional seats finally vacated by aged New Deal Democrats, was Phil Gramm. The East Texas professor would become a leader among conservative House Democrats known as Boll Weevilssouthern pests to Congresss Democratic leaders, but allies to Reagan. Like some other Boll Weevils, Gramm soon would jump to the Republican Party, speeding its rightward, southern-based makeover.

By 1980, when Texas turned on Carter and embraced Reagan, I was in Austin covering politics for a chain of fourteen state newspapers. On election night, Id barely made it to the states Republican Party headquarters to cover the vote watch there before the networks, shortly after polls closed in the East, projected Reagan would be the winner. Not only that, but the Senate would have a Republican majority for the first time since Dwight Eisenhowers first term.