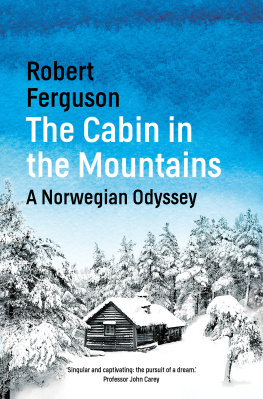

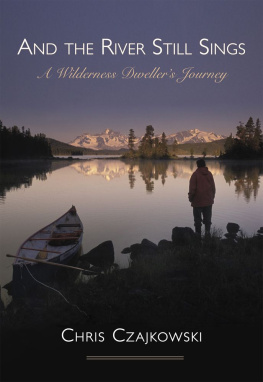

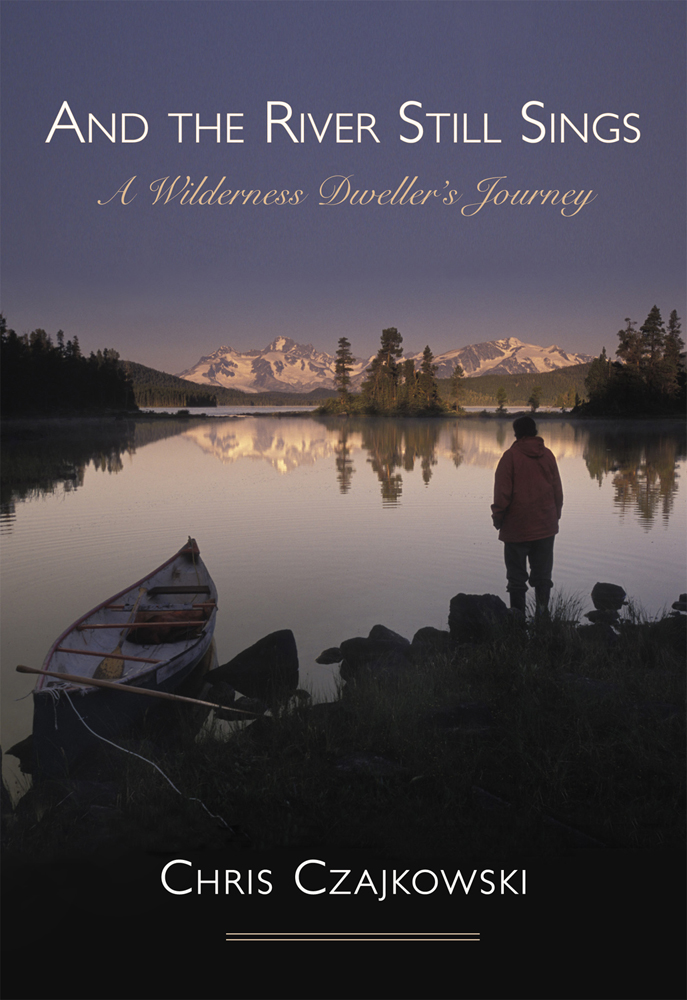

And the River Still Sings

A Wilderness Dweller's Journey

Chris Czajkowski

Copyright 2014 by Chris Czajkowski.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without prior permission of the publisher or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from Access Copyright, the Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency, .

Caitlin Press Inc.

8100 Alderwood Road,

Halfmoon Bay, BC V0N 1Y1

caitlin-press.com

Text design and EPUB by Kathleen Fraser.

Cover design by Vici Johnstone.

Cover image copyright Patrice Halley Photography.

Caitlin Press Inc. acknowledges financial support from the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund and the Canada Council for the Arts, and from the Province of British Columbia through the British Columbia Arts Council and the Book Publishers Tax Credit.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Czajkowski, Chris, author

And the river still sings : a wilderness dwellers journey / Chris

Czajkowski.

ISBN 978-1-927575-62-8 (EPUB)

1. Czajkowski, Chris. 2. Outdoor lifeBritish ColumbiaChilcotin

Ranges. 3. Wilderness survivalBritish ColumbiaChilcotin Ranges.

4. SolitudeBritish ColumbiaChilcotin Ranges. 5. Women travelers

Great BritainBiography. I. Title.

GV191.52.C93A3 2014 796.5092 C2014-904079-2

Once upon a time there was a queen living in the land of the morning sun and the crooked woods. It was a big and beautiful queendom and there were a lot of contented subjects living in it. First there were the flowers. They had a big gathering every year in the meadows below the treeline and the queen walked all the way to the meadows to join the gathering. The flowers know that she will be coming and so they put [on] their most beautiful colours to impress the queen

One day a musician travelled through the queendom and stayed for a few days. The queen showed him the way through the mountains behind the palace and he had some of the most beautiful days in his life He promised to come back and see her again.

Janis Bikos, written in the guest book at Nuk Tessli

All experience is an arch wherethrough

Gleams that untravelled world whose margin fades

Forever and forever when I move

Tennyson, Ulysses

Contents

Introduction

I sit by my window and wait for a plane. This is something I have done many times during the last thirty years. The plane might already be threading the air between the mountains from the float plane base forty-five kilometres north, but I have no means of finding out for sure. I am not by nature a patient person, but indeterminate waits for light aircraft have been an integral part of my life for more than half of it, and I am by no means young. Most people prefer to fly in this country. There are no roads: the only other way to get here is to carry a camp on your back, and walk.

It is a beautiful, late June morning. The ice went out about three weeks ago; the lake is blue and sparkling, and the low mountains that lift beyond the far shore are still thickly brushed with snow. Behind me, out of sight from where I sit, much bigger peaks sprawl across the horizon. They are bound with the chains of winter, and they will stay wrinkled with glaciers even at the end of a hot, dry summer; now, the winter snow lies heavily upon them. It is from these mountains that the wind comes: the west wind that is called nuk tessli in the Carrier language. It can scream like a banshee and pound like a demon, forcing me to fit my life around it. When the winter blizzards boom and roar I shrink within the cabin walls and wait for them to end. I called the small resort I have created here in honour of it: Nuk Tessli. I can never forget the winds power. But when blackflies hover in a swarm around my head, or a float plane needs to take off with a maximum load on a hot day, nuk tessli is a friend. The breeze that comes from the mountains this morning is perfect for flying; it does no more than fracture the sunlight on the lake into sparkling shards.

Nuk Tessli, the resort, comprises three cabins: two I built alone, and the last one with some help. They cluster loosely on a squarish point of land jutting into a lake only three hundred metres below the treeline. There are no other buildings for many kilometres in any direction and certainly nothing else on the lake; the nearest man-made structure is a days walk away, an outlying cabin belonging to a resort near the float plane base. It is occupied only during the height of the short tourist season, and has never been used as a home.

The scrubby upper montane forest that surrounds Nuk Tessli is much battered by the elements and distorted by mistletoe and other diseases. Some of the trees are lodgepole pines, a species that is universal to most of western Canada, but about half are whitebark pines (a very different tree to the eastern white pine). Whitebarks grow only at high altitudes. When I first came here, I did not know this tree existed, but was puzzled by artifacts that I occasionally found on the aromatic duff between the boulders on the forest floor: cones that looked like a corn cob stripped of its grain, and shells of what appeared to be a small nut. Few people had travelled this country on foot, and even fewer could distinguish this tree, but I eventually learned that this pine had a cone resembling a resin-encrusted hand-grenade. It enclosed wingless pine nuts. The nuts never fall out of their container and cannot be spread by wind, but the tiny capsules are rich in oil and much sought after by squirrels, birds and even grizzly bears. The Clarks nutcracker, a small black, grey and white crow that is common in the area, has a symbiotic relationship with this tree. It caches seeds in open spaces and never eats them all, thus repopulating forests after a burn. The whitebarks timber has a pretty pinkish cast to it, but it makes a soft, weak lumber that splits easily, so I used lodgepole for the main structures of the cabins and whitebark for wall fillers and floorboards.

When I first stood on this point a quarter of a century ago, I had eyes only for the spectacular view. It was August and the weather was brilliant. I thought nothing of the problems that might arise trying to establish myself in such a remote and difficult spot. I had already built one cabin in the wilderness and I expected challenges, but failure did not enter my mind. Two years later on a dull day in early July, when I came to start building and really looked at the place, the awful logistics of manoeuvring logs single-handedly over the tumbled pile of boulders made me wonder if I was crazy. I almost gave up right then. But I made the first chainsaw cut, felled the first tree, and Nuk Tessli was born.

The de Havilland Beaver I am expecting today will come from Nimpo Lake. The forty-five-kilometre flight will take twenty minutes, a far cry from the overland journey, which may require as much as four days in winter. I have occasionally managed it in a fourteen-hour summer hike made in a single day, but conditions could never be guaranteed and I always carried a camp.