Published by

Whittles Publishing,

Dunbeath

Caithness, KW6 6EG,

Scotland, UK

www.whittlespublishing.com

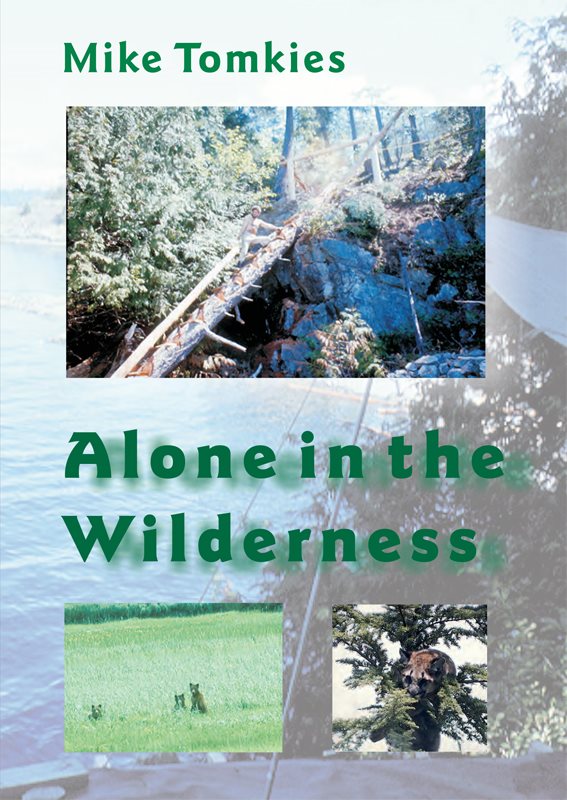

Text and photographs 2001; Mike Tomkies

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted,

in any form or by any means, electronic,

mechanical, recording or otherwise

without prior permission of the publishers.

ISBN 10 1-870325-14-1

ISBN 13 978-1-84995-255-2

For those who love the last of the wild

Also by Mike Tomkies

Books

My Wicked First

Life Between Earth and Paradise

A Last Wild Place

My Wilderness Wildcats

Liane A Cat from the Wild

Wildcat Haven

Out of the Wild

Golden Eagle Years

On Wing and Wild Water

Moobli

Last Wild Years

In Spains Secret Wilderness

Wildcats

Videos

Eagle Mountain Year

At Home with Eagles

Forest Phantoms

My Barn Owl Family

River Dancing Year

Wildest Spain

P ausing from my four-mile row, I lay back in the leaky boat and looked over the Pacific Ocean at a wilderness world I could hardly believe was now mine. From the shores of Telnarko Island, the sun bridled a liquid track of gold across the sea like a dazzling path to the heavens. In the distance flowering arbutus trees fringed the lone firs on grey granite islands, while below me in the green waters a school of salmon lazed by. Mesmerized, I watched a rainbow form from a sea mist and touch the nearest island, like a finger from the sky. Drifting gently on the sea, I turned to look at the rocky two acres of my homestead claim in British Columbia. Was it possible this small bay and beach, these trees, this incredible view the good place for which Id searched so long was really now my own?

A few months earlier my whole life had hung in tatters. At nearly forty, a thoroughly urbanized man and former journalist whose life in the big cities of Europe had become stale and pointless, I had fled from London and all we loosely call civilization to emigrate to Canada to write in the ancient silence of the wilderness what I hoped would be a successful novel, and start a more meaningful life.

Before my move from Britain, I had found myself becoming bored and depressed. The reasons perhaps reached back to my youth. During early years as a cub reporter in country villages, I had dreamed only of making it to London. The British capital then seemed to me in my painful navety a magic journalistic mecca where Id be accepted into an exciting world of earls, politicians, glamorous women, movie stars, and athletes.

After more than a decade in London, I indeed dallied with the illustrious, the beautiful, and the swift. I was flying between Paris, Rome, Athens, Madrid, Vienna, New York, and Hollywood, mixing drinks, talk, life, love and copy with vaunted famous names whose images Id once worshipped as a village youth. Meeting whom I chose, writing about whom I liked, my name at the head of columns in widely read magazines, money simply flooding in, I became the complete hedonist. I went through sports cars like a frustrated racing driver and reacted against my shy and awkward country-bred youth by squiring some of the worlds most beautiful women.

It was around my thirty-fourth birthday that this fast life and material success began to go sour. Quite suddenly, nothing seemed to lie ahead but boring repetition. A self contempt grew, fuelled by the advice of two of my close women friends, Ava Gardner and Eva Bartok, both of whom told me I ought to be doing something more intelligent with my life.

Society, too, was changing. The new pop culture where foppishly dressed youth gyrated like battery-reared chickens to the hellish din in discotheques did not attract me. Neither did the hippie drop-out rebellion, the new anarchists from comfortable homes whod never seen their democracy threatened, nor the students demanding freedom when theyd never known anything else. Britain herself seemed to be degenerating into a land of bingo, brain drain, and backbiting, living on international credit, overworking and underpaying her most essential workforce doctors, nurses, police, farmworkers and allowing the unions to hold the rest of society to ransom. It was a disenchantment I shared with many, and most of us failed to appreciate that similar problems were affecting the rest of the developed world as well.

Even my once-beloved London seemed to have become a noisy trap. In the last four years I had changed apartments three times to find a quiet place in which to work. But within a week the workmen would arrive and out would come the noisy drills and up would come the road the water, gas, and electricity authorities often digging up the same stretch within days of each other.

After a severe illness, my first since childhood, I asked myself, When were the good times? Ironically my thoughts returned to the peace and tranquil silences of the wild woods and dappled fields of my childhood. The memories came flooding back my first holiday in the country as a town-reared boy of twelve: I had walked through forests of waving bluebells and nodding wild narcissus, heard the strident call of the green woodpecker, and from the marshes the plaintive love call of the lapwing. Alone, I was transported into a creation more miraculous than I had ever known could exist. Beautiful jays flashed their rainbow wings and white rumps as they weaved screeching through the still shadows of the pines, purple emperor butterflies sunned the glossy sheen of their wings on old oak stumps, grasshoppers leaped and fiddled in the summer hay, and in the twilight bats flew on skinny wings around the caves of our isolated cottage. I had never been happier in my life. Now I hankered to dwell once again among the scenes of my youth. For a few months I rented a thatched cottage near those old haunts, but I soon found my dream of pastoral bliss there had passed away. The woods were smaller, the rivers muddier, and the fishing lake where the bronze carp had whirled the limpid waters, where coots had bobbed their white pates and the great blue dragonflies had hawked above the reeds like darting wands of fire, was now only a large silted pond surrounded by marsh. The thick hedges that had teemed with wildlife had mostly been dug up. The song of the nightingale came seldom from the thickets, for most of the thickets had gone. I had forgotten my country memories were those of a child, that I had retained only the tiny focus of boyhood. A man can never go back. Yet still I longed to return to more basic values, to live close to nature again.

By now my parents had emigrated to Spain and the only person left of my immediate family was my grandmother. When I drove up to see her in Nottingham, where she lived near her sister and friends, she told me an incredible story; before she had married my fathers father, David Tomkies, he had wanted to go to Canada but she had refused to go with him. One night he arrived outside her house and threw gravel at her window. Im off to Canada, he told her. After working as a waiter on the Trans-Canadian Express, he had settled down in Calgary, Alberta, as a cowpoke. One day, returning from a beer parlour with friends, he had been ambushed by a group of stone-throwing Indians, his right eye knocked out so that it rested on his cheek. Patched up by local doctors, he was sent to a specialist in Vancouver who told him the best eye surgeon was a Dr. Watts, who lived in Nottingham! Back he had come, had his eye treated, and visited my grandmother again, who this time accepted him. She told me he had been full of stories of how great a land Canada was, of its vast, untouched wild places. As she spoke I remembered with a slight shock that as a child it was a book called