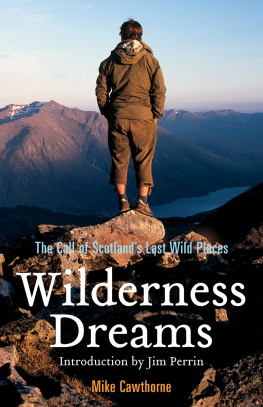

Praise for Wilderness Dreams

Mike Cawthornes Wilderness Dreams takes us romping through some of Scotlands wildest places: a canoe trip down the River Dee, a blizzard in the Monadhliath, the dangers facing the Flow Country in Sutherland. The heart of the book, though, is the story of an expedition across the Munros in 1986, accomplished on no money and with falling-apart boots, and despite an occasional over-excitement in the landscape description, this is exciting stuff, and its written with humanity, passion and a touch of anger. For anyone who loves the Scottish hills, this is a book to read.

From the speech announcing the winner by Lord (Chris) Smith

Boardman Tasker Awards, Kendal, 16th November 2007

This is descriptive writing of a very high order. It could have been written by Stevenson, Buchan or Neil Gunn.

Alan Taylor, Sunday Herald

Mike Cawthorne shows both his talent for writing and his deep affinity with the wilderness areas of Scotland in this book. I read his collection of essays in a very short time, finding each one hard to put down. As well as being a fascinating account of Mike's own experiences of hillwalking in Scotland, his essays are an enlightening education on the commercial greed that has damaged, and continues to damage, Scotland's natural landscapes. Read this book and you'll be absorbed, entertained, outraged, educated, humbled and, ultimately, inspired to experience the beauty of Scotland's wild places for yourself.

Review by K Jackson on Amazon

Praise for Hell of a Journey

He is a marvellously evocative writer ... this is work born of a deep sense of connection and love. Kathleen Jamie, Boardman Tasker Prize for Mountain Literature

Cawthorne is a great embracer of life ... his remarkable journey is not simply another travel tale pitting man against the elements; it has a political hue. Scottish Review of Books

Mike Cawthorne can truly write. To some extent, the author was trying to find himself and the elusive secret of the appeal of the hills. He succeeds in describing that without appearing precious, no easy matter The Scots Magazine

... a man with mountains coursing through his blood High

Written with wry humour and illustrated with stunning photographs this compelling book is testimony to his indomitable spirit. The Scotsman

The style is refreshingly honest and extraordinary open in terms of the authors emotions. We are privy to the inner and outer tortures brought about by spindrifts and steep climbs as every detail of his surroundings is captured in this fascinating diary Scotland on Sunday

A crazy idea but it makes for great reading. Big Issue in Scotland.

Mike writes evocatively of the winter hills his prose radiates a sense of serene contentment, whether he is battling to the tops or lying patiently in his tent waiting for the weather to improve. This is an engaging and heart-warming narrative, well-deserving of attention from hill-goers. Far from being a hell of a journey, this is a wonderful journey. TGO.

Mike writes compellingly about the thinking behind such an apparently insane journey and youre pulled through this book with a mixture of morbid curiosity and anticipation for when it all comes good. Trail.

For Anne

Contents

Acknowledgements

In writing this book I am indebted to a number of people. From the other side of the world, my good friend Dave Hughes responded to my flurry of letters with typical generosity and openness. The story at the core of this book is as much Daves as mine. To all those I burdened with enquiries or requests, and who responded so helpfully, I am very grateful, namely Mike Dales, Andrew Duke, Peter Duncan, Dr James Fenton, Ian Hewines, Angus Mcfadyen, Cathel Morrison, Edward Morrison, Robbie and Anne Northway, Jock Sutherland, Will Boyd-Wallis and Andy Wightman. For help in compiling the fascinating place-name glossary I have to thank Roddy Maclean and Peter Drummond, both acknowledged experts in their field. I take full responsibility for any errors. For friendship on the hill and river and who, willingly or otherwise, appear in these pages, I thank Geraldine Cawthorne, Clive Dennier, Nick Crutchley, Claire Higgins and Paul Winter.

My thanks to Neil Wilson, my publisher, for his shrewd guidance and sharp eye, and to Jim Perrin, a writer Ive long admired, for his excellent Introduction.

Preface

I have always been drawn to wilderness. Growing up in a city I was lucky to live close to a large area of common land, about two square miles of wood and scrubby plain which, thanks to a community-minded politician and an arcane law, had somehow managed to escape the bulldozers and developers. An untidy oasis in a desert of suburbia, it was only accessible through a network of mysterious, semi-hidden pathways. As soon as I could ride a bike, with two or three friends we began to nibble at the edge of this jungle, in time growing more confident, broadening our range, until there was a day when we went to find the legendary Caesars Well. Lost in murky woods, having a tooth and nail battle with bushes and wiry brambles, crossing an oily stream to a strange savannah with yellow grass, following our noses and the sun, knowing only that we were a long way from home and that our mothers would be hopping mad. When we found the well it was choked full of black sludge and did not seem particularly Roman. But it didnt matter; wed had the best day of our lives.

While these early forays would later develop into a more specific love of mountains, they were never less than adventurous, fulfilling a childhood craving for space, freedom and discovery. Our common supplied all of that and more, a young explorers paradise with its chaotic vegetation, its apparent lack of human features and the dark rumour of a gypsy man living rough somewhere within it. A parentfree zone, it was unfenced, overgrown and, unlike the local park, you werent kicked out at dusk. It was free and it was freedom.

At the time I was probably no different from any other child in filling my head with the mythic worlds of fantasy writers and screen animators. I remember watching my first Disney flick in a smoky cinema, and sitting rapt in a crowded classroom as my primary schoolteacher read aloud CS Lewiss Tales of Narnia. But I always found real places more alluring than imaginary ones. Thanks to free-spirited parents, even before I could walk, I was taken to distant parts of the country on wild camping trips (my father had an anathema for campsites) and saw at first hand the stone-covered mountains of the north, the windswept moors and dizzy coastlines. Under the cloak of parental tutelage I didnt have the run of these places but I did climb my first mountain, Ben Nevis, and from that day my world changed.

Remembering where a love for the outdoors first began is a useful exercise, for somehow on that long journey from childish adventures to adult enjoyment something is lost perhaps the very thing that drew us there in the first place. What we did instinctively and naturally as soon as we were able to walk has, by the time we reach our teens, become just another sport or pastime, burdened with all the baggage of justification. Activity has taken precedence over place. Something extraordinary happened to me on my first Scottish mountain, and I need an adult vocabulary to articulate it the ethereal mist, the lunar rock, the sight and feel of snow in August, the terrible, sheer abyss of the north-face cliffs, a combination of all these or a recognition, however dimly, that I was being touched by something as loose and indefinable as beauty. It was nothing to do with numerical lists, with heights metric or imperial, with equipment or navigational aids or miles walked or feet climbed, nothing to do with sport, not about schedules or technical competence or graded ability.