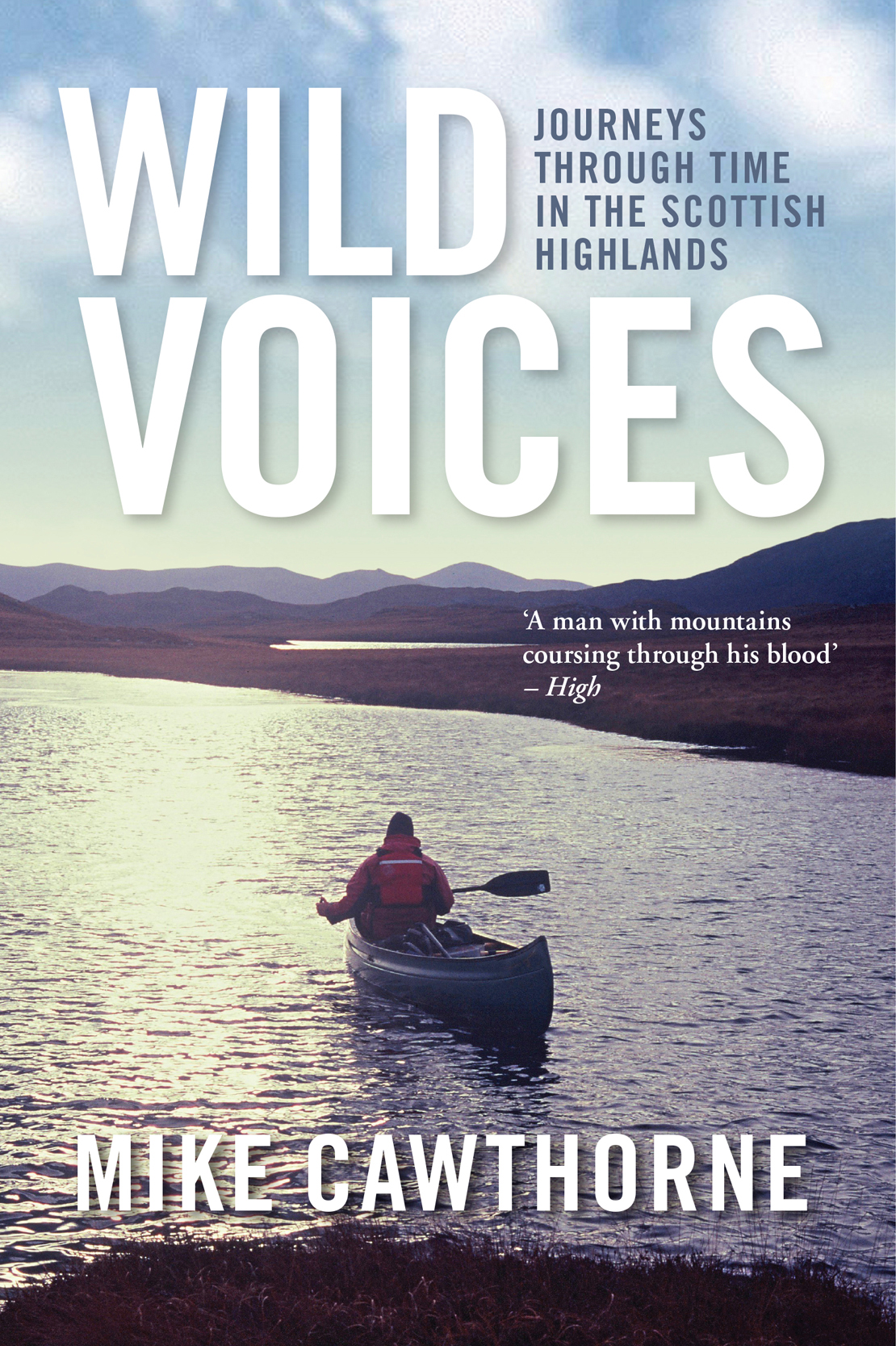

WILD VOICES

Mike Cawthorne began hill-walking on Ben Nevis aged seven, and has been climbing mountains ever since. He has worked as a teacher, professional photographer and freelance journalist. His first book, Hell of a Journey: On Foot through the Scottish Highlands in Winter (2000, new edition 2007) was short-listed for the Boardman Tasker Prize for mountain literature. His second book, Wilderness Dreams, was published in 2007. He lives in Inverness.

This eBook edition published in 2014 by

Birlinn Limited

West Newington House

Newington Road

Edinburgh

EH9 1QS

www.birlinn.co.uk

Text and photographs Mike Cawthorne, 2014

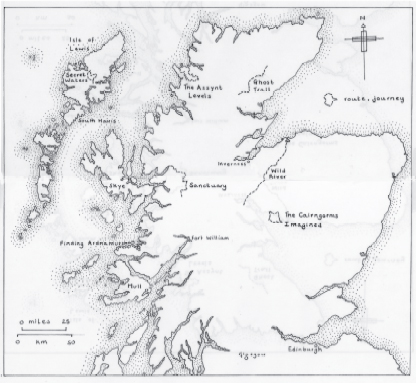

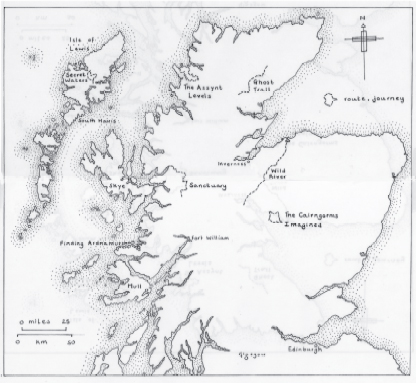

Maps Francis Byrn, 2014

The right of Mike Cawthorne to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Design and Patent Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission of the publishers.

eBook ISBN: 9780857907950

ISBN: 9781780271927

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Contents

Illustrations

Maps

Preface

In the anonymity of a hillslope above Loch Monar in Wester Ross is a water-filled cleft. I stumbled across it one blazing hot day in April. It was cool and shady in there. I sat for a while, then I began to follow it upstream, picking over polished stones and feeling along water-smoothed sides. It went deep into the hill and at the same time opened out. A small waterfall spilled onto a great angular rock that had once belonged to the side of the mountain. The whole world was there. The story of a stream and a hill in its making. Though I have searched I never found it again, but it runs clear in my mind and I know that out there somewhere the stream still goes around rocks and over pebbles and collects in pools and sings in voices and holds in its watery palm the sun and sky.

Which is how I remember it at any rate. Probably the great conundrum of outdoor writing, maybe any writing, is to bridge the gulf between what we see and feel and what we are able to capture on the page and present to the world. In that spirit are undertaken the journeys in this book, tales of adventure on foot and by canoe through some of the last wild places in Scotland. Each journey is haunted by another writer, someone whose passion for a region was for me a large part of its appeal. I wondered how my experience would differ from those of, say, Iain Thomson, or Rowena Farre. In the case of novelist Neil Gunn the experience I am sharing is that of the fictional Kenn. Gunns lyricism chimes with his subject matter a boy seeking the source of a river, and himself. I hoped that by entering into the spirit of a similar journey on this occasion by following the River Findhorn I might have an insight not only into the character of Kenn but discover a truth about the river, and maybe even about life.

The exploration of the lochans of Assynt deepened my belief that, regardless of ownership, here is a place so beautiful and unspoilt it cries out for legislative protection. We cannot any longer rely on benevolent landowners to keep out developers with their wind-farm and hydro proposals. Canoeing the extraordinary loch system there was an adventure partly inspired by the poet Norman MacCaig, who wrote prolifically about this area and often passed his long holidays here. A part of Assynt was one of the first in the Highlands to come under community ownership when it was purchased by local crofters in 1988. But MacCaig in his long poem A Man in Assynt, which predates the community buyout, asks whether something so ancient in provenance and beautiful and open to all can in fact be owned. This raises the question, does ownership matter? It certainly does to cash-strapped crofters.

In Ardnamurchan there is probably no greater dichotomy than that between how locals view a place and the experience of visitors. Or at least there was. It is about as far west as you can reach in mainland Britain, a peninsula of achingly beautiful beaches and a stark rocky coastline. But dont worry it for a living. Alasdair Macleans parents were the last crofters here to try and it nearly broke them. The author needs metaphors when weighing his own and his parents experience, and perhaps to make it palatable for the reader he somehow manages to elevate their story to the level of a fable, though underlying his elegant narrative are sweat and tears and crushed hopes. It informed deeply my own trek around the wild Ardnamurchan coast.

Rowena Farres tale of growing up with her aunt Miriam on a remote croft in the shadow of Ben Armine in Sutherland before the war, along with a menagerie that included a seal, a pair of otters and a pet squirrel, is altogether happier. She and her aunt embraced their isolation and revelled in the solitude, drawing what they needed from the land, and Miriams allowance. The idyll painted by Farre was lapped up by reviewers and thousands of readers, but a few questioned the books authenticity. A copy had lain for years on my parents bookshelf, and later in life I realised I knew the empty moorland of the storys backdrop. Setting out to uncover its truth or otherwise would also give me an opportunity to revisit, perhaps for the last time, a truly wild area before its industrialisation by huge wind turbines.

Like many who love wild places I am torn on the issue of wind farms. To do our bit to moderate the effects of global warming probably requires the expansion of this form of energy, yet I am saddened when our diminishing portions of wildland are used for this purpose.

It is a dilemma that author and environmental campaigner Alastair McIntosh is only too aware of. Focusing largely on his native Hebrides, he catalogues our appalling history of disconnection with the natural world, but he offers hope as well, with tales of opposing the corporate interests behind the Harris superquarry and supporting the Isle of Eigg community buy-out. McIntoshs vision is for humanity to readjust its relationship with nature. Id long wanted to explore the lochs of Lewis, close to where McIntosh had lived as a child. What, I wondered, did his message hold for these quiet, rarely-visited backwaters?

Maybe a deep attachment to any one place can only be nurtured through a prolonged stay in that place. Iain Thomson spent five years in the mountain fastness at the west end of Loch Monar, living with his family in a small croft that was then one of the remotest dwellings on mainland Scotland. Thomsons memoir has an overriding elegiac quality, for reasons that become apparent.

Living remotely and usually self-sufficiently in the Highlands had been the norm for millennia, though it was unusual by the time Thomson took up his posting in the mid-1950s, and virtually unheard of when his book appeared some twenty years later. Readers, including this one, were fascinated. I wondered if books like Thomsons tap into an age-old yearning for the wild and lonely places, whether our present day stravaigings there are just that. And I discovered something else. The land the author so lovingly portrays and was forced to leave is now more developed, more moribund and emptier than at any time since prehistory.