ELSPETH TURNER grew up in the Scottish Borders. She held a senior lectureship in Economic and Social History at the University of Edinburgh and is returning in retirement to these and other storytelling roots after career shifts to facilitate equal access to higher education for school leavers she was the first Director of Lothians Equal Access Programme for Schools and later a researcher and co-author in the field of Childrens Rights with her husband, the late Stewart Asquith. She latterly worked for the Scottish Funding Council and lives in Edinburgh.

DONALD SMITH is a storyteller, novelist and playwright and founding Director of the Scottish Storytelling Centre. He was also a founder of the National Theatre of Scotland, for which he campaigned over a decade. Smiths non-fiction includes three previous Journeys and Evocations , co-authored with Stuart McHardy, Freedom and Faith on the Independence debate, and Pilgrim Guide to Scotland which recovers the nations sacred geography. Donald Smith has written a series of novels, most recently Flora McIvor . He is currently Director of Traditional Arts and Culture Scotland.

First published 2017

ISBN: 978-1-912147-21-2

The paper used in this book is recyclable. It is made from low chlorine pulps produced in a low energy, low emissions manner from renewable forests.

Maps OpenStreetMap contributors (www.openstreetmap.org), available under the Open Database License (www.opendatacommons.org) and reproduced under the Creative Commons Licence (www.creativecommons.org).

Printed and bound by Bell & Bain Ltd., Glasgow

Typeset in 10.5 point Sabon and Din by 3btype.com

The authors right to be identified as author of this work under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 has been asserted.

Photographs (except where indicated) and text Elspeth Turner and Donald Smith 2017

Dedicated to

The late Nancy and

Hamish Turner and the bairns

of their Border bairns

and

David, Jean, Mary,

Pat and Nancy Smith,

children of Kirkurd Manse

Acknowledgements

The idea for this book was sparked by our involvement in the Seeing Stories project which explored links between landscape features and stories connected with them in four European regions. The choice of the river Tweed catchment was an obvious one not least because the Scottish Borders was so fortunate in their recorders and interpreters, most notably James Hogg, Sir Walter Scott and Robert Chambers. In modern times, John Veitchs History and Poetry of the Scottish Border , W. S. Crocketts The Scott Country , Walter Elliots The New Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border 18052005 , and Alastair Moffats The Scottish Borders have all added to the treasury, and we acknowledge our debt to the insights and materials collected by their authors and to those to whom they were indebted. Amongst the storytellers past and present, John Wilson, Sir George Douglas, Andrew Lang, John Buchan, Winifred M. Petrie, Jean Lang, and, in our own day, James Spence, Walter Elliot and Charlie Robertson have kept the tales of the Tweed Dales flowing.

Our thanks too to the poets who, inspired by the landscape, lore and history of the area, gave us a wealth of evocative words with which to illustrate the journeys. We thank Tim Douglas, Mhairi Owens, Isabella Johnstone, Dorcas Symms and Catriona Porteous for permission to quote their work and Will H Ogilvies trustees for permission to quote his. Among the song makers we thank Eric Bogle for permission to quote from his original composition No Mans Land, and Janette McGinn for permission to quote from her late husband Matt McGinns song The Rolling Hills of the Border. Last but not least, thanks to the many who shared information, memories and stories with us, to Fiona Melrose and, for his assistance with photographs, Gordon Melrose.

Contents

Introduction

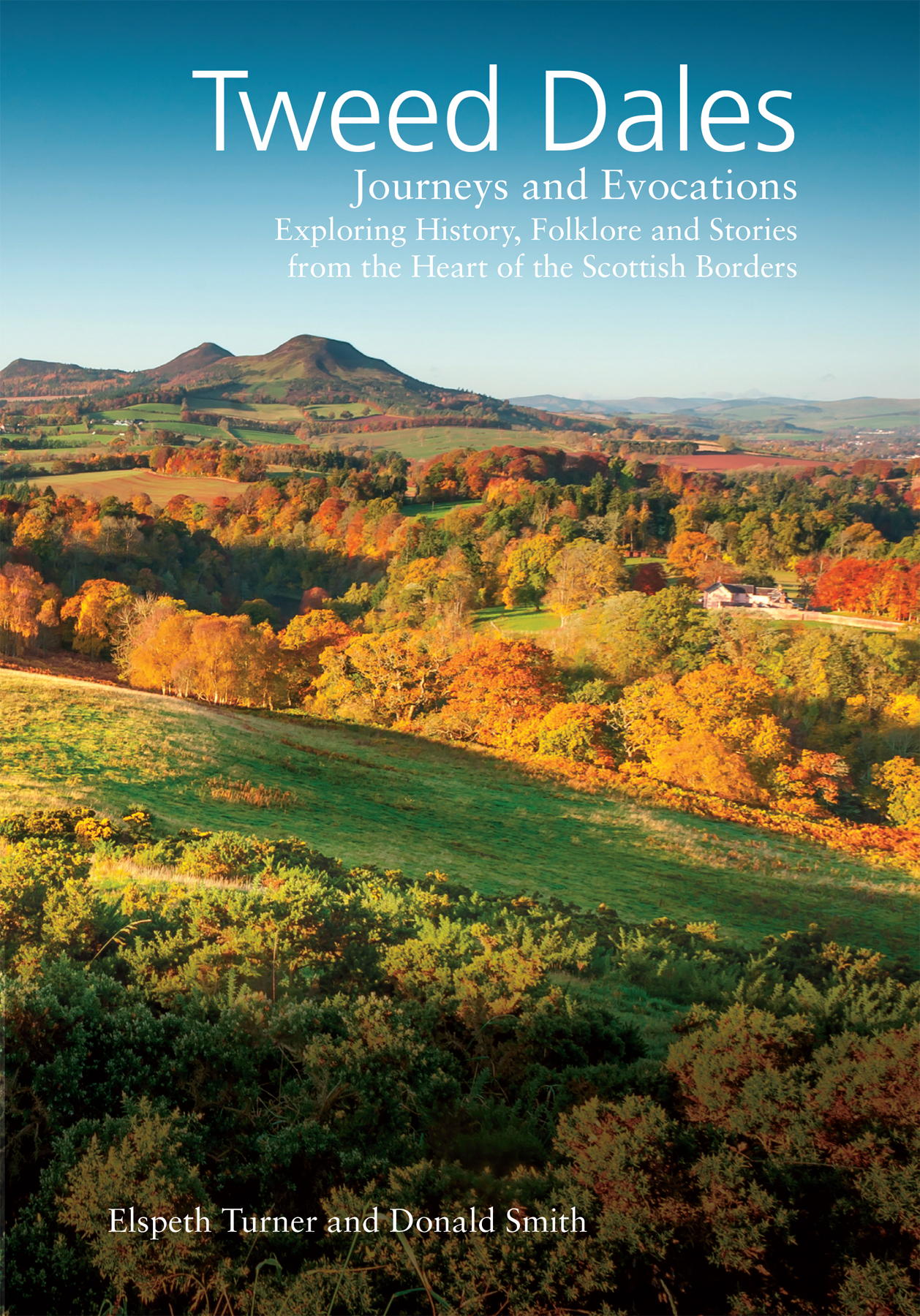

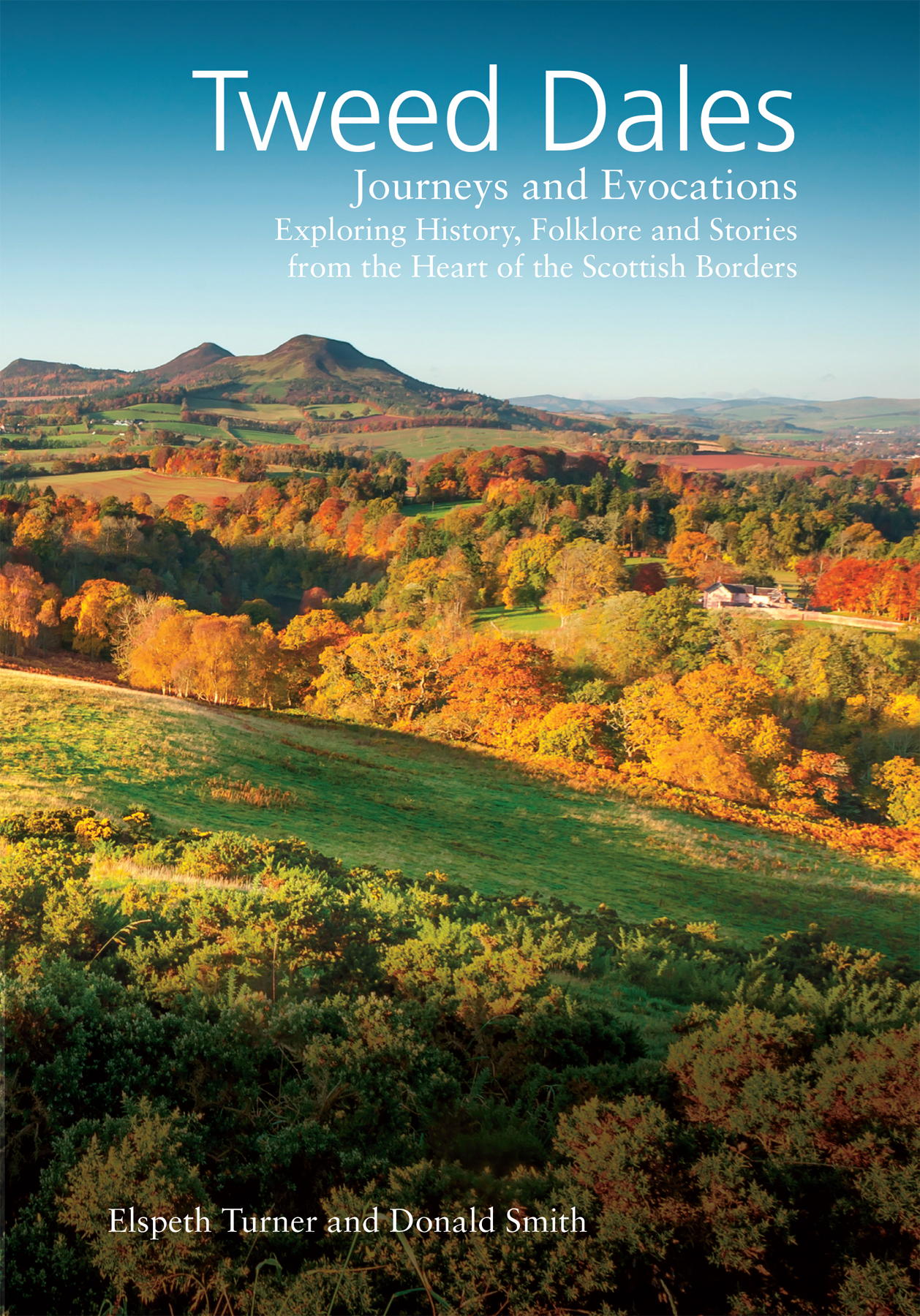

The Scottish Borders lie between the Moorfoot and Lammermuir Hills to the north, and the Cheviot Hills and England to the south. People born and raised in this part of Scotland have a mindset that is neither Scottish nor English. They are Borderers. Their outlook and experience is as distinctive as the landscape and its geographical position within mainland Britain. These have their origins in geological events and are the context for the ebb and flow of people bringing new ways of seeing and doing things.

The landscape and the tussles for political, economic and spiritual control influenced how Borderers understood their world, and also their cultural and spiritual experience. Indeed, the landscape and its topographic features had a profound influence on the minds of the many visionaries, mystics, writers, thinkers, innovators and artists who came from or were inspired by this area.

There was a particular fascination with hills and rivers. Hilltops, especially those with wide vistas or panoramic views, are important to invaders and defenders of any land, and also have an influence on how travellers experience it. Hills look different depending on the angle of approach and the means by which you approach them: on foot, by horse, by train, car or plane. All the hills of volcanic origin in the Borders look small seen first from high ground north, west or south of them. But they grow and change colour when you travel, as the early settlers did, down into the river valleys to reach them. The hill that looks like one hill can become two or three as your angle of approach changes and even, as the Eildon Hills do, four.

This shape-shifting quality, and the fact that people raised animals and took them to high summer pastures, might explain why hills feature so prominently in Border folk tales and legends. Hills are where fairies live, where sleeping armies rest, where the membrane between this and other worlds is thinnest, and where people disappear. These stories have their origins in the beliefs of the earliest settlers for whom the shape of the landscape was important. They revered nature, the land and trees.

Sometime later, the spiritual focus of the early farmers switched to celestial beings and the changing of the seasons. It took many generations and the development of religious institutions for monotheistic Christian beliefs to first overlap and then overtake primeval belief systems in the Scottish Borders. As late as the 13th century, the learned men of Europe believed not only in the existence of stars and planets but also in the predictive power of astrology. They combined knowledge of the physical world and the healing power of plants with alchemy and the presumed magical properties of substances. It was said that one such individual journeyed overnight on a flying horse to carry out diplomatic missions. Another claimed to have spent seven years with the fairies beneath the Eildon Hills and returned with the gift of prophecy. We meet Michael Scot and Thomas the Rhymer later.

There was magic in the hills but there was also something in the water. The river Tweed brought water and people together as it headed for the North Sea. Rivers loom large in Border history, legend, story and ballad. Until roads and railways snaked across the landscape, the easiest way to travel was along river valleys. As the towns of today bear witness, junctions of rivers were convenient places to trade goods and to meet for ceremonial events. Water has a special and enduring place in rituals and spiritual beliefs, while the junctions of rivers were associated with movement between one world and the next. Rivers and their banks also feature prominently in tales of family honour with their avenged and ill-fated lovers. The Tweed and its tributaries played a big part in shaping the outlook and mindset of Borderers.

Next page