Contents

Part I

Part II

Part III

Part IV

Introduction

Elliott Merrick: A Reminiscence

M y friend and northern mentor Elliott Merrick passed away on April 22, 1997, although as a sworn enemy of contemporary jargon, he would have asked me not to use a phrase like passed away to describe his demise. So let me just say that he died three weeks before his ninety-second birthday. Toward the end of his life, he would joke that he was so old that hed become historical. In fact, he was one of the last surviving links with pioneer Labrador, a place that makes the present-day Labrador of jet overflights, nickel mines, and Native slums seem like another country.

Raised in Montclair, New Jersey, Budas he was known to his friendswas educated at Phillips Exeter Academy and Yale University. His first job was as a reporter for the Passaic Daily News; he drove to work in a model-T roadster that hed bought from his brother-in-law for $2.50. In 1928 he became assistant advertising manager for the National Lead Company, his fathers firm. But how could a young man for whom Thoreaus Walden was almost a sacred text devote his heart and soul to producing copy for Dutch Boy paints?

Merricks escape from the much-despised business world came in 1929, when he signed on as a summer WOP (Worker without Pay) with Labradors Grenfell Mission. He fell in love with Labrador (that pristine, beautiful land, he called it) and stayed on as a schoolteacher in North West River. He also fell in love with the missions resident nurse, Australian-born Kate (Kay) Austen. They were married in 1930 and for a time lived in a small cabin near where Goose Bay Airport now stands.

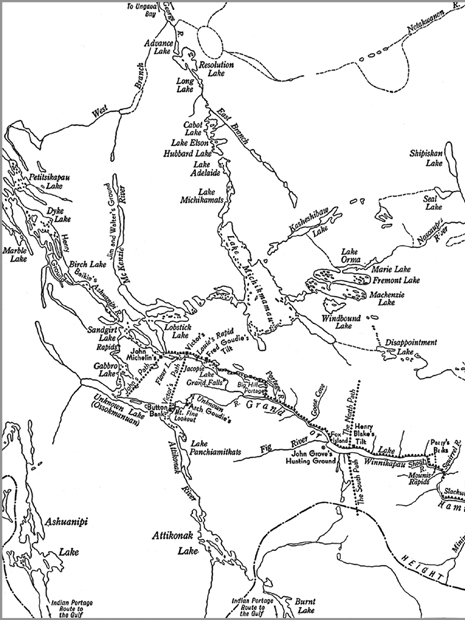

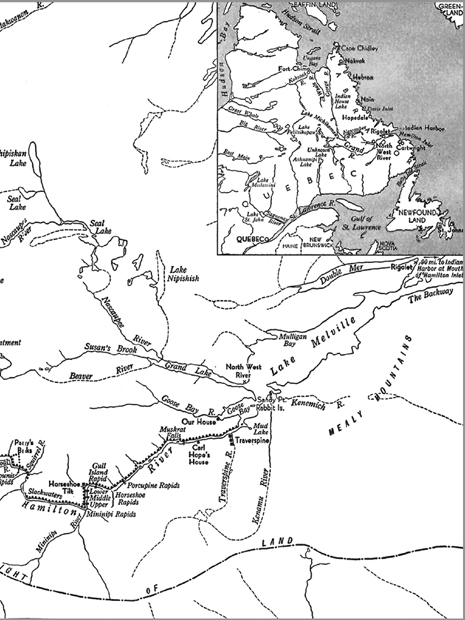

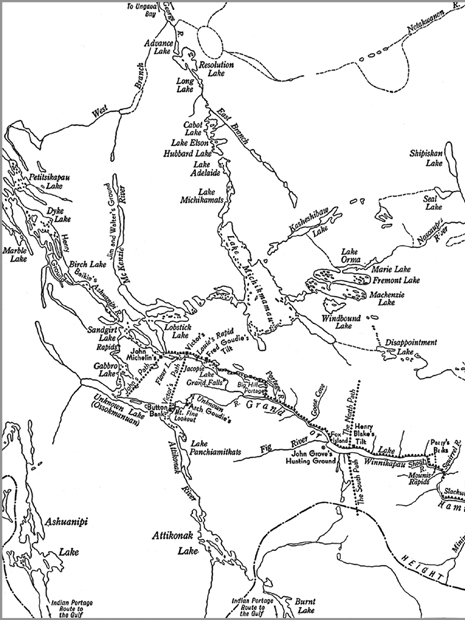

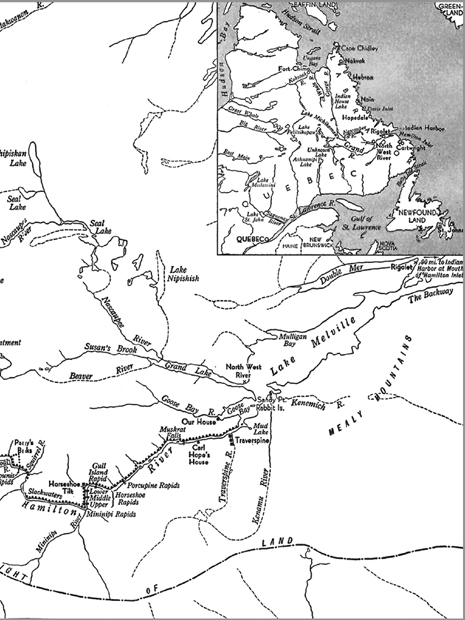

Probably the high point of his Labrador years was a trip he and Kay made with trapper John Michelin. They journeyed by canoe and portage up the Grand (now the Churchill) River and then continued by snowshoe and toboggan deep into the bush. All together, they covered more than three hundred miles. Their encounter with a virtually unexplored wilderness more than made up for the trips frequent hardships. In his journal Bud wrote, We have traveled to the earths core and found meaning.

The Merricks returned to the United States in the early 1930s. The day I left Labrador was the saddest of my life, Bud wrote me, adding: A major in English literature from Yale did not prepare me for a trappers life. Eventually, they bought a hardscrabble farm in Vermonts Northeast Kingdom, one of the few parts of the United States that could ever be mistaken for Labrador. Indeed, the similarity of northern Vermont to Labrador probably gave Bud the distance he needed to write about the latter.

True North, his account of his time in Labrador and the trip with John Michelin, was first published in 1933. The book so enthralled its Scribners editor, the legendary Maxwell Perkins, that he reputedly asked Bud if there was any work he could do in Labrador. True North has had the same effect on later readers, many of whom now include it as an essential part of their outfit on northern trips. The book is a Walden of the North, its voice now celebrating the boreal wilderness, now inveighing against the urban wilderness. I dare say its antiurban, antitechnological message is more relevant today than when the book was originally published. Looking back on True North sixty years later, Bud often said that its most significant feature was its portrait of trappers and settlers. He wrote me, They were remarkable men and women whose way of life disappeared not long after the book was published disappeared with WWII and the coming of planes that began to crisscross the formerly mysterious North. I was so lucky to have spent time with them. And yet its not these people themselves but Merricks experience of them and his ability to convey that experience in such sharp detail that make True North a classic of northern literature. What also makes it a classic is a lyrical style that would turn most poets green with envy.

Merrick continued writing about Labrador in his slightly fictionalized autobiography, Ever the Winds Blow (1936), a novel titled Frost and Fire (1939), and various magazine pieces. Then, drawing on his wifes experiences as a nurse with the Grenfell Mission, he wrote Northern Nurse (1942). This last book is arguably the finest ever written about the North from a womans perspective. It was reprinted in 1994 (that it should have been out of print for over fifty years says a good deal about the odd priorities of publishers), thus giving a whole new generation of readers a window on a way of life that is now historical itself.

The exigencies of raising a family forced Bud to give up writing, at least full-time writing, for work that was somewhat less haphazard. He spent twenty-two years as a science editor and publications officer for the U.S. Forest Service in Asheville, North Carolina. After he retired, he built a small boat and sailed it to Maine, a trip described in his posthumous book Cruising at Last (2003). Meanwhile, devotees of his books would journey to his farm outside Asheville as if on a pilgrimagea pilgrimage not so much to a saint (Bud hated everything sanctimonious) as to an elder whose wisdom we could always rely on. But he was an elder so remarkably young in spirit that I often felt like telling him, Pack up your bags, my friend. Were hopping the next dogsled for points north. Bud was a man who always nailed his colors to the mast.

He once told me about an author on Arctic themes whose work he disapproved of: Her new book burned quite well in my woodstove. It was obvious that he disapproved of my neoprene and aluminum snowshoes as well. I wrote him about their efficacy during a winter trip I made to Hudson Bay. He wrote back, I have invented a snowshoe far superior to your aluminum ones. Its frame is composed of old garden hoses, which bend readily, taking either the bear-paw shape or that of the Alaska tundra runner. Crossbars are of Victorian corset stays bound together with baling wire, and the mesh is of state-of-the-art chicken wire layered in an intricate pattern. I am depending on you as a qualified expert to see that my creation is installed in the Smithsonians Hall of Artifacts. At the same time he remained a dedicated, albeit curmudgeonly advocate of the Thoreauvian belief that most human inventions are eminently expendable. Writing to me after a severe winter storm struck the Asheville area, he said, The roads are so icy that almost everyones been marooned. We havent lost our power yet, but even if we do lose it, Uncle Bud just happens to have lived in a part of the world that did not have running water or electricity. I weep, of course, for those whove lost their e-mail, their online, their Internet, and their electronic revolution. So sad!