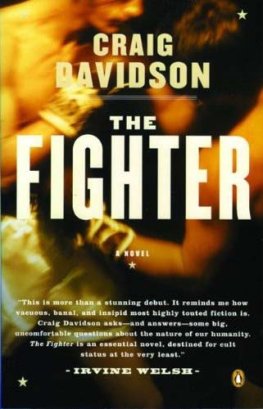

The Fighter

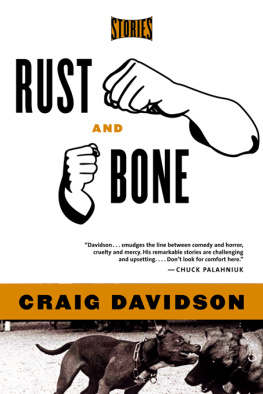

Craig Davidson

Firstpublished 2006 as a Viking Canada Book by Penguin Group, Canada

Firstpublished in Great Britain 2007 by Picador

animprint of Pan Macmillan Ltd

PanMacmillan, 20 New Wharf Road, London N1 9RR

Basingstokeand Oxford

Associatedcompanies throughout the world

www.panmacmillan.com

Copyright Craig Davidson 2006

A great fighter is a man alone ona path.

He must feel that he is themaker, not made.

He must feel that he fatheredhimself.

Gary Smith

'Cause all I ever wanted was justa little thing

just to be a man.

Chester Himes

Table of Contents

Prologue

Theysay a man can change his personalitythe basic essence of who or what he isbyfive percent. Five percent: the total change any one of us is capable of.

Atfirst it sounds trivial. Five percent, what's that? A fingernail paring. Butconsider the vastness of the human psyche and that number acquires real weight.Think five percent of the Earth's total landmass, five percent of the knownuniverse. Millions of square acres, billions of light years. Consider how achange of five percent could alter anyone. Imagine dominoes lined in neatstraight rows, the world of possibilities set in motion at a touch.

Fivepercent: everything changes. Five percent: a whole new person.

Consideredin these terms, five percent really means something.

Consideredin these terms, five percent is colossal.

Iwake in a dark space. Blinking, disoriented, a dream-image lingers: a namelessface split down the center, knotted brain glimpsed through a bright halo ofblood.

Atight bathroom. Peeling wallpaper, mildewed tiles. Stripped bare, I wash myselfat a stone basin. My body is utilitarian: bone and muscle and skin. Apurposeful body, I think of it, though from time to time I miss that old spryness.To look at me, you might believe I entered the world this way.

Mylegs: crosshatched with scars from machete wounds I took in the northernplantations harvesting sugarcane before moving south to the cities. Anarrow-shaped divot is gouged from my right shank: on sleepless nights I'll runa finger over the spot, the hardness of shin- bone beneath a quarter-inch ofscar tissue.

Mychest: networked with razor wounds, mottled with chemical burn scars. Lyefightsour fists wrapped in heavy rope smeared with a mixture of honey andpowdered lye. A sand-filled Mekong bottle stands beside the cot; I hammer mystomach for hours, hardening my flesh for combat.

Myhands: shattered. Knuckles split in dumdum Xs humped over in skin that shinesunder the bathroom light. They've been brokenhow many times? I've lost count.So brittle I once cracked my thumb opening a bottle of soda.

Blindin one eye: those damn lye fights. My upper incisors driven through my gums,half embedded in soft palate. Cauliflower ears jug ears, my old trainer would've saidand my hearing cuts in and out like a radio on thefritz; when it goes I'll smack the side of my head, the way you would a finickyTV to get the picture back. A raised line runs from the base of my scalp to apoint between my eyebrows: my skull was split open on the concrete of an emptyoil refinery. An unlicensed medicthere's no other kind around herewrapped aleather belt around my head to keep the split halves together. This woundhealed into a not-quite-smooth seam like blocks of wax heated along their edgesand pressed gently together.

Theysay a man's body is a map of his existence.

I'mshrugging on a pair of floral-print shorts when the telephone rings. It's awarm evening; the air is heavy with the scent of something, though I can'tquite place what.

Thephone falls silent. I know what the caller wants. I know what night this is.

DuringWorld War II the roof of the Boeing aircraft factory outside Seattle wascamouflaged to look like a fake city. There were little buildings, the sameshape as regular buildings, only about five feet high. The streets were made ofburlap; the trees were wire mesh topped with green-painted beach umbrellas.They even had mannequins: mannequin mailmen and milkmen; mannequin housewivespinning laundry on wash lines. A Hollywood set designer oversaw the wholething. The buildings and houses had depth to themglimpsed from overhead by aJapanese bomber pilot, it would look like a quiet residential neighborhood.Under this fake city was the factory, where construction went on around theclock. During wartime, a B-17 Flying Fortress rolled off the line everyseventy-two hours.

I'vecome to realize all societies are much like this. On top you've got the worldmost live in, a safe and sanitary place, airbrushed, a polished veneera worldI now find as fake as those five-foot buildings and mannequins must have seemedfrom ground level.

Underneathlies the factory, which few know of and fewer still venture into.

Theplace where the war machines are built.

Thestreets rage with bicycles and Tuk-Tuks and pickup trucks. An old woman skewersshark fins on a length of piano wire in the greasy light of a deli. Clusters ofshirtless men crouch in fire-gutted alleys passing bottles of Mekong. Oneshouts as I walk pastcatcall or cheer? I've never learned the language.

Youngforeign men all around. Talking too loudly, spending too much, laughing atnonsense. Drunk on Mekong, some will return to their rented rooms withcross-dressing locals they've mistaken for women. There was a time when I couldcount myself one of their number. Their life was my life, their wants my own.But now, recalling the man I once was, it's as though I'm considering someoneelse altogether.

Afigure stands before a metal door set into an alley wall. His face, halfshrouded by the lapels of his duster coat, is netted with old razor scars. Thenickel-plated hammers of a Rizzini shotgun jut through the folds of his coat.

"Youon tonight?"

WhenI nod the man steps aside.

"What'reyou waiting for, assholethe Queen's invite?"

Thedoor is gunmetal gray, set in a brick wall touched black by old fires. I knock.A slot snaps back. A pair of dark considering eyes. The deadbolts disengage.

Thehallway is lit by forty-watt bulbs behind wire screens. Cockroaches feast onmildew. I roll my shoulders and snap my neck, limbering. Quick jabs, shortpuffing breaths. I plant my lead foot the way my trainer instructed years ago: Pretend a nail's pounded through the damn thing, okay? Turnon that point, now, pivot hard. Work that power up through your feet, legs,hips and arms and handsbam!

Anotherdoor leads into a prep room the size of a tiger cage. Wooden benches set at intersectingangles. The smell of resin and sweat and wintergreen liniment. A chicken-wireceiling allows bettors to size us up before placing wagers. They can be realbastards: my scalp is pitted with burns from the Zippo-heated coins they flickthrough the wire.

Theother fighters lounge on benches or pace restlessly. Scars and welts andbruises, missing ears, not a full set of teeth among them. My father once toldme to never trust the word of a man whose body was not a little ruined. Ifthere is any truth to that, these are some of the most trustworthy men onearth.

Icheck out their bodies. That guy's got a slight limphis left side is weak.That guy's wrist is bent at a peculiar angleit's been busted once and couldbust again.

Afighter known as Prophet comes in. A burn scar in the shape of a crucifix markshis chest, self-inflicted with an acetylene torch. Tattooed above the crucifix: cry havoc . And below: let slip the dogs of war.

Next page