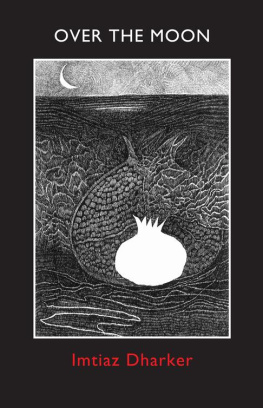

IMTIAZ DHARKER

OVER THE MOON

Imtiaz Dharker was born in Pakistan, grew up a Muslim Calvinist in a Lahori household in Glasgow, was adopted by India and married into Wales. Her main themes are drawn from a life of transitions: childhood, exile, journeying, home, displacement, religious strife and terror, and latterly, grief. She is also an accomplished artist, and all her collections are illustrated with her drawings, which form an integral part of her books.

Over the Moon is her fifth book from Bloodaxe. These are poems of joy and sadness, of mourning and celebration: poems about music and feet, church bells, beds, caf tables, bad language and sudden silence. In contrast with her previous work written amidst the hubbub of India, these new poems are mostly set in London, where she has built a new life with and since the death of her husband Simon Powell.

This is a passionate, uplifting collection of poems about language, love and loss, grief and joy, elegy and celebration. The loss of a great love makes poems of piercing beauty. In her finest book to date, Imtiaz Dharker finds resolution in language itself, and in a world the more loved for the sharpness of loss Gillian Clarke. Imtiaz Dharkers new collection is the crown to a celebratory, humane, wholly utterable, subtly crafted poetry. Its dark jewels are the magnificent poems of bereavement, which will surely endure. Reading her, one feels that were there to be a World Laureate, Imtiaz Dharker would be the only candidate Carol Ann Duffy.

Cover drawing by Imtiaz Dharker for Simon Powell,not because you diedbut for how you livethe telegraMcAme.i Read it.death we expeCtbut all wE getis Life JOHN CAGE for Marcel Duchamp

At the sign of the black flip-flop crossed off in red, by the door of the Ganesh temple, you are obliged to take off your shoes, and this you do. In the face of all the silent watchers on the steps, you bend, struggle to undo the laces and come up pink, not, as a stranger might think, out of embarrassment. No, you point at your foot in its black sock, and there, escaping it, the pale slug of your naked toe. You laugh because you know, as all the watchers do, that this is the way of things. A sock inside a shoe is deemed immaculate. A sock exposed to public view, especially on its way to god, will grow a hole.

Even the master of symmetry knew this to be true. When Gabriel and the dove fly in, the fabric of the day wears thin and frays around the virgins face. Light folds itself over a boys head and he is shirtless, shivering, but believes the Baptist will turn from the main event before too long to tend to him. You make a kind of offering of frailty, an opening for the world to show its grace and as you point, the watchers, children, street-dogs, bottom-scratchers become your family. You are a foreigner nowhere.

This music will not sit in straight lines.

This music will not sit in straight lines.

The notes refuse to perch on wires but move in rhythm with the dancer round the face of the clock, through the dandelion head of time. We feel blown free, but circle back to be in love, to touch and part and meet again, spun past the face of the moon, the precise underpinning of stars. The cycle begins with one and ends with one, dha dhin dhin dha. There must be other feet in step with us, an underbeat, a voice that keeps count, not yours or mine. This music is playing us.

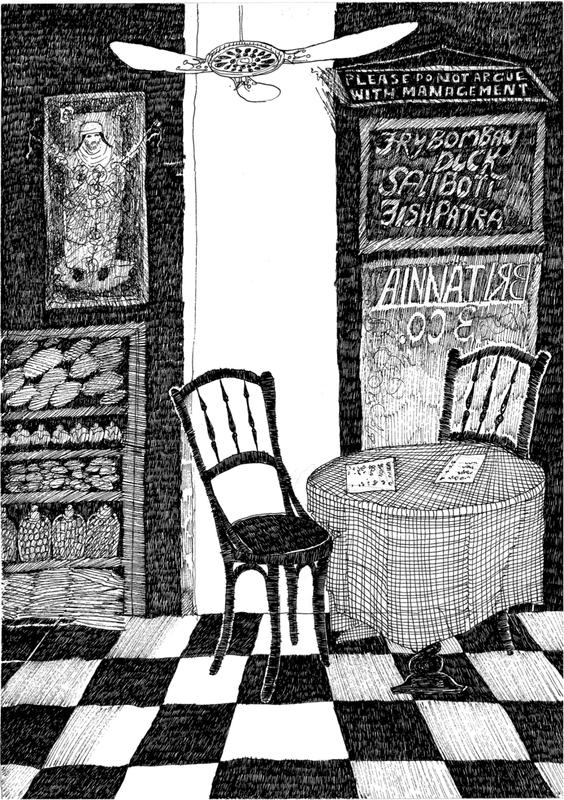

At Britannia Caf on Ballard Estate late one afternoon, the poet was discovered buying Bombay Duck to take away, waiting to have it wrapped up in a brown paper bag before he carried it home fresh-fried and hot.

At Britannia Caf on Ballard Estate late one afternoon, the poet was discovered buying Bombay Duck to take away, waiting to have it wrapped up in a brown paper bag before he carried it home fresh-fried and hot.

This was where, by chance, you met. Simon Rhys Powell and Arun Kolatkar sat on bentwood chairs and talked about the art of frying and eating Bombay Duck, how the bones were soft and melted down the throat, how it could be swallowed whole, with limba-cha-ras, just like that. The poet smacked his lips, you ate his words as if they were Welsh, both of you savoured the name itself, the taste on your tongues of Bombil, Bummalo, Bombay Duck. Two strange fish swimming in the mirrors of the caf like long-lost friends, bosom-buddies brought together by a stroke of luck. Two lives too big to be packed away in a brown paper bag like a take-away, you will stay, you will still be there on Ballard Estate when the boxwallahs have come and the boxwallahs have gone.

Waking to Jurassic sounds of crows above the banyan trees, the distant hawking, spitting, radios switched on, a hundred stereo TVs, our bodies afloat in underwater light and the night a foreign country, this is how we learn each other, half-asleep, in a language that invents itself again at dawn, sometimes remembers itself, sometimes forgets, and surprises us, calling out at windows we have left wide open.

We are waving to you from up here, from the fourth floor to say dont worry about us, we are fine.

We are waving to you from up here, from the fourth floor to say dont worry about us, we are fine.

We may be strung out, trousers vest blouse sari skirt on this washing line but the sun is being kind to us. Better here than down there where you are passing on the Number 106, crammed into a hot window frame with your loud loneliness. We are floating here, our hearts filled with soft evening air and the sound of conversations in the rooms behind us, in love with the shape of each other and the dance we make together, waving to you, sending a sign that you would see if you were looking but you are not.

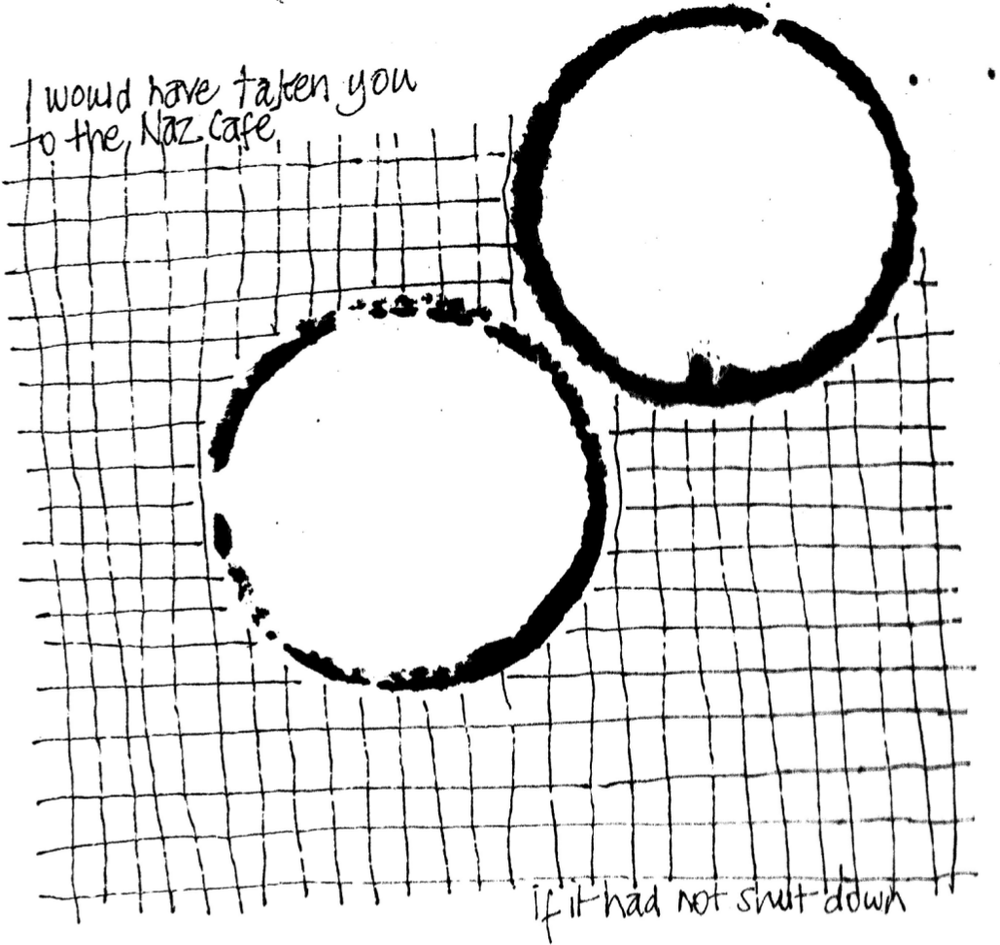

I would have taken you to the Naz Caf if it had not shut down. I would have taken you to the Naz Caf for the best view and the worst food in town. We would have drunk flat beer and cream soda and sweated on plastic chairs at the Naz Caf.

We would have looked down over the dusty trees at cars creeping along Marine Drive, round the bay to Eros Cinema and the Talk of the Town. We would have held hands in the Naz Caf over sticky rings on the table-top, knee locked on knee at the Naz Caf, while we admired the distant Stock Exchange, Taj Mahal Hotel, Sassoon Dock, Gateway. We would have nursed a drink at the Naz Caf and you would have stolen a kiss from me. We would have lingered in the Naz Cafe till the day slid off the map into the Arabian sea. I would have taken you to Bombay if its name had not slid into the sea.