Contents

The

History

of Wales in

Twelve Poems

Im teulu am ffrindiau oll, sy ac a fu.

And in memory of Neil Reeve (19532018).

The

History of Wales

in Twelve Poems

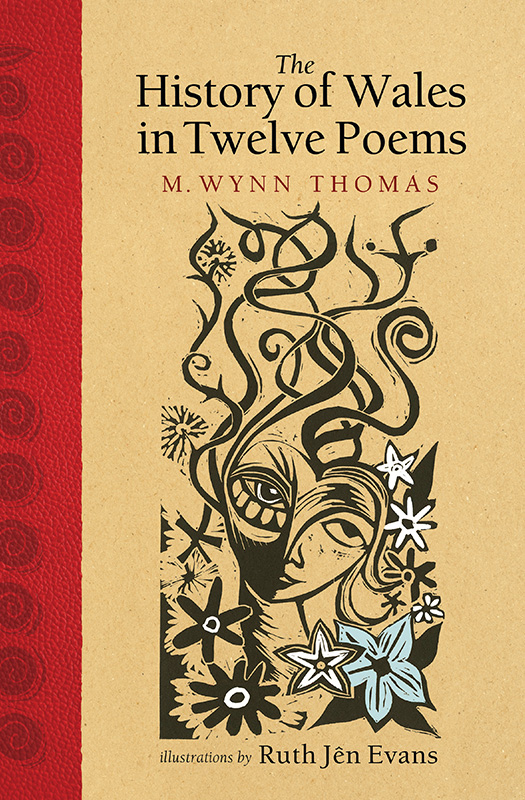

M. WYNN THOMAS

Illustrations by Ruth Jn Evans

Text M. Wynn Thomas, 2021

Illustrations Ruth Jn Evans, 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing it in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the copyright owner. Applications for the copyright owners written permission to reproduce any part of this publication should be addressed to the University of Wales Press, University Registry, King Edward VII Avenue, Cardiff CF10 3NS.

www.uwp.co.uk

British Library CIP Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-1-78683-766-0

eISBN 978-1-78683-768-4

The right of M. Wynn Thomas to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 79 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Cover design: Olwen Fowler

Powerful nations have great poets;

small nations have tragic poets.

They do our dying for us, whisper the

powerful nations, sensing the insecurity

of their power. In this way we produce

great poets, whisper the small nations.

George Szirtes

Aneirin, Y Gododdin, Thomas Parry (ed.), Oxford Book ofWelsh Verse (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), pp. 12; trans. M. Wynn Thomas.

Anon., Pais Dinogad, Thomas Parry (ed.), Oxford Book ofWelsh Verse (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), pp. 78; trans. Tony Conran, Welsh Verse (Bridgend: Seren Books, 2003), p. 117.

Anon., Stafell Gynddylan, Thomas Parry (ed.), Oxford Book of Welsh Verse (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), p. 12; Cynddylans Hall, trans. Tony Conran, Welsh Verse (Bridgend: Seren Books, 2003), p. 12.

Gruffydd ab yr Ynad Coch, Marwnad Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, Thomas Parry (ed.), Oxford Book of Welsh Verse (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), pp. 478; Elegy for Llywelyn ap Gruffydd, trans. Tony Conran, Welsh Verse (Bridgend: Seren Books, 2003), p. 163.

Dafydd ap Gwilym, Trafferth mewn Tafarn, dafyddapgwilym.net; trans. M. Wynn Thomas.

Henry Vaughan, The World, L. C. Martin (ed.), Henry Vaughan,Poetry and Prose (London: Oxford University Press, 1963), pp. 299301.

Anon., Hen Benillion, T. H. Parry-Williams (ed.), Hen Benillion (Llandysul: Gwasg Gomer, 2010), pp. 289; Harp stanzas, trans. Glyn Jones, A Peoples Poetry: Hen Benillion (Bridgend: Seren Books, 1997), pp. 1601.

Ann Griffiths, Welen sefyll rhwng y myrtwydd; See there stands, trans. Joseph P. Clancy, Other Words: Essays, Poetry and Translation (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1999), p. 27.

Gwenallt, Y Meirwon, Christine James (ed.), Cerddi Gwenallt:Y Casgliad Cyflawn (Llandysul: Gwasg Gomer, 2001), pp. 13940; The Dead, trans. Tony Conran, Welsh Verse (Bridgend: Seren Books, 2003), p. 163.

Dylan Thomas, Fern Hill, Walford Davies and Ralph Maud (eds), Dylan Thomas: Collected Poems, 19341953 (London: Dent, 1988), pp. 1345. 1945 by the Trustees for the Copyrights of Dylan Thomas. Reprinted by permission of New Directions Publishing Corp. and David Higham Associates.

Gillian Clarke, Blodeuwedd, Collected Poems (Manchester: Carcanet, 1992), pp. 6970.

Menna Elfyn, Siapau o Gymru/The Shapes She Makes (trans. Elin ap Hywel), Eucalyptus (Llandysul: Gomer, 1995), pp. 98101.

H aving, like their cousins the Irish, a long, ancient taproot in a Celtic culture, the Welsh have always revered the number three. From the ancient Tribannau and Trioedd Ynys Prydain, to the three feathers in the badge of the medieval Prince of Wales, to the persistence to this day of the popular saying Tri chynnig i Gymro (Three tries for a Welshman), the three has been accorded mystic status. And in modern times, even the phrase three tries has taken on a different meaning, as the Welsh rugby team have a distinguished record of winning the premier home nations title of the Triple Crown. With all of this in mind, let me conform to established cultural practice and offer three reasons for writing this book.

First, there is the plight of the Invisible Nation. When, half a century ago, I read Ralph Ellisons classic novel Invisible Man (before discovering it had been begun when he was a GI in Swansea), what struck me even beyond its unforgettable account of the complex fate of being an African-American was that the narrative had unexpectedly offered me a fascinating glimpse of myself. I was of course fully aware that there was not the slightest comparison between my own sorry plight and the immense tragedy of Ellison and his people, but I still couldnt help reflecting that I too knew what it was to be invisible. From an early age, I had intuited that the Welsh were not only invisible to the world at large, but that they were also, tragically, mostly invisible even to themselves. That invisibility deriving as it obviously does from long centuries of subordination, marginalisation, and assimilation has continued to haunt and to frustrate me. This brief history is therefore an attempt to make my Wales just a little easier to see.

As for the second reason for writing, it can best be expressed through the story of Tinker Bell. She, it will be remembered, is the fey fairy in J. M. Barries Peter Pan. Yes, she can be mischievous, wilful, even spiteful, but in the end she is a deeply poignant creation. Her very existence, signified by the frail glow of light she emits, is entirely dependent on there being children enough who stubbornly continue, even in the face all the scoffing scepticism of the modern world of adult experience, to believe in fairies. And as the narrative proceeds to its conclusion, so does Tinker Bells fragile gleam grow ever fainter, extinguished at last in the darkness of her total extinction.

The Welsh, I have long felt, are not only an invisible people, they are a Tinker Bell of a people. For almost as long as the history of Wales itself, theirs has had to be a survivor cultures precarious, conditional, identity. Devoid of the robust supporting mechanism of an established state, and lacking the complex infrastructure necessary to ensure the safe transmission of a national culture, the Welsh have had no choice but to exist by effortfully choosing to do so and by constantly improvising strategies of self-renewal. In no other instance than theirs has Renans famous description of nationhood as a daily plebiscite seemed more apt. This mini-history is therefore an attempt to ensure that the light of this Tinkerbell people continues to burn for a short while longer, at least.

And thirdly? Well, it concerns the poets. Wales is often recognised as the home of significant singers, from stars of popular culture such as Shirley Bassey, Tom Jones and Katherine Jenkins to giants of the operatic stage, such as Bryn Terfel, Gwyneth Jones, Geraint Evans and Rebecca Evans. Welsh actors likewise enjoy a good reputation for their acting, if not always for their lifestyles witness Richard Burton, Anthony Hopkins, Sin Phillips, Michael Sheen and Catherine Zeta Jones.