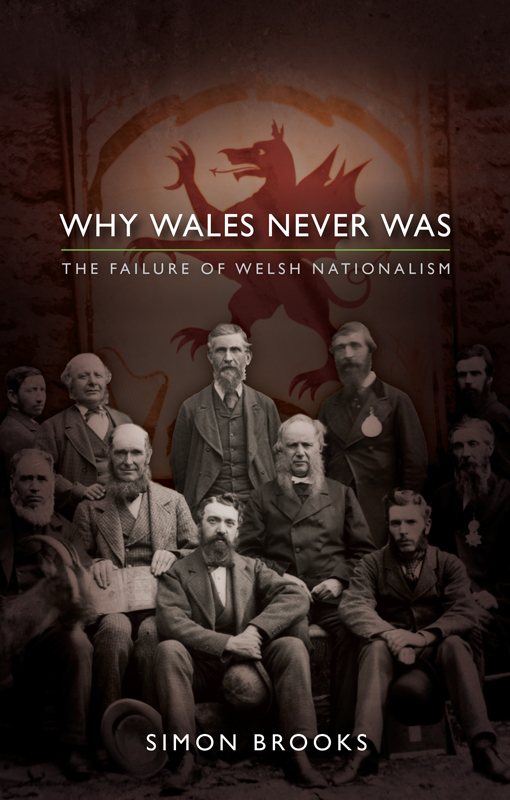

WHY WALES NEVER WAS

Why Wales Never Was

The failure of Welsh Nationalism

Simon Brooks

Simon Brooks, 2017

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing it in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the copyright owner except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Applications for the copyright owners written permission to reproduce any part of this publication should be addressed to the University of Wales Press, 10 Columbus Walk, Brigantine Place, Cardiff CF10 4UP.

www.uwp.co.uk

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-1-7868-3012-8

eISBN 978-1-78683-014-2

The right of Simon Brooks to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with sections 77, 78 and 79 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This book was first published in Welsh in 2015 by the University of Wales Press as Pam na fu Cymru: Methiant Cenedlaetholdeb Cymreig (ISBN 978-1-78316-233-8; e-ISBN 978-1-78316-234-5), in the series Safbwyntiau: Gwleidyddiaeth Diwylliant Cymdeithas.

The University of Wales Press acknowledges the financial support of Swansea University and the Welsh Books Council.

The publisher has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for any external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Cover design: Olwen Fowler

Cover image: John Thomas, Beirdd Llanrwst (The Poets of Llanrwst), c.1875. From the John Thomas Collection at the National Library of Wales, reproduced by permission.

I Richard Glyn Roberts a Daniel G. Williams

Dirmygaf finau Ryddfrydiaeth pob dyn sydd yn credu mewn goresgyniad.

(I truly despise the Liberalism of every man who believes in subjugation.)

Michael D. Jones

Acknowledgements are noted, and thanks given, in Pam na fu Cymru, and readers of this English edition who read Welsh are referred to the original text of which Why Wales Never Was is an adaptation. I am grateful nevertheless to Marion Lffler, Richard Glyn Roberts, Daniel G. Williams, Shintaro Kono, Takashi Onuki, Huw Williams, Dylan Foster Evans and Syd Morgan for their help at various times with the development of the English edition. Broadly speaking, it follows the Welsh original, although some sections have been expanded.

As ever, I am grateful to the staff of the University of Wales Press for their professionalism and enthusiasm.

I am grateful too to Shintaro Kono and Takashi Onuki for their willingness to translate a synopsis of Pam na fu Cymru into Japanese, due to be published in 2018. I am also thankful to the Wales Literature Exchange for sponsoring a discussion tour around Pam na fu Cymru in Slovenia in April 2016, and for arranging the translation of a text into Slovene. The visit followed on from a Welsh tour, entitled Pryd bydd Cymru?/When will Wales be?, undertaken with Daniel G. Williams in the summer of 2016, visiting Caernarfon, Aberystwyth, Swansea, Montgomeryshire, the Rhondda and Cardiff.

Research was carried out in a number of academic and public libraries in Wales, Germany, Austria, the Czech Republic and Slovenia. I lived in Germany, on and off, for the best part of a year. But by the time I came to write the book I was unemployed.

Pam na fu Cymru was written on the dole in Porthmadog. I wrote it in cafes, I wrote it in pubs and I wrote it in the street.

In his autobiography, Bob Owen, from Croesor, a village near Porthmadog, writes of going down to Porthmadog to sign on every week in view of all who went by the circumstances were nearly enough to make me a Bolshevik. The experience of two years unemployment was a revelation for me too, and I am hugely thankful to the people of Porthmadog for their support at this time. Rural Welsh-speaking Gwynedd has been left behind by both London and Cardiff; it is a disgrace.

As I wrote Pam na fu Cymru, the political winds changed in Wales. Scotland seemed likely to claim independence, and Britain toyed with the idea of leaving Europe. The book became a book about crisis; the crisis of Britain, the crisis of Europe, and in the midst of all this the absolute irrelevance of Wales.

Swansea University agreed to finance the publication of Pam na fu Cymru, and have done so again with Why Wales Never Was. Without their financial support, neither book would have seen the light of day. I thank them too.

I write these words on a warm, wet July day in Porthmadog, Gwynedd. It has been a glorious June, the dazzling run of the Welsh football team to the semi-finals of the Euro 2016 football competition our first appearance at a finals since 1958 having redefined Welsh popular culture for the better. Sitting with my son in the Parc Olympique Lyonnais during the semi-final was to be in the Wales in which I wish to live. Welsh culture defined as Welsh, embracing the Welsh language, open to ethnic diversity too; an independent nation on the global stage, at one with our European neighbours. Independence in Europe indeed.

Along the horizon, dark clouds: the absolute disaster of the Brexit vote. Are we to be trapped on a wet archipelago reliving in the twenty-first century our nineteenth-century servitude? Save us indeed from incorporation into an England and Wales nation state, and the fight within between an English nationalism of the right, led by Ukip and Brexiters, and an English nationalism of the left, led by Billy Bragg and Owen Smith to the chorus of Jerusalem.

Here in Gwynedd, where some still believe in Welsh cultural nationalism, we voted to remain in Europe. But Wales voted to leave. The vote for Brexit was heaviest in those parts of English-speaking Wales where the Welsh-born population forms the greatest part of the population, and where cultural nationalism is at its weakest.

The success of Ukip in securing seven seats at the 2016 assembly elections, and in persuading the Welsh to vote to leave Europe, confirms with horrible accuracy predictions made in Pam na fu Cymru in 2015. In retreating from the nation, from culture and from language, Welsh civic nationalism has not abolished ethnicity, culture and language. All it has done is allow Ukip to define these on its own terms. In the 1960s and 1970s, the National Front and other racist organisations could never gain a foothold in Wales. The discursive space of ethnicity, identity and culture had been filled by the anti-racist and anti-colonial politics of an assertive Welsh language and Welsh national movement.

Since devolution, however, campaigning for the language, and creating narratives of Welsh nationhood, have been eschewed by Welsh nationalists in favour of raising buildings in Cardiff Bay. Much of Wales has been abandoned as back country. The conditions for the Brexit vote in Wales were created in part by the eclipse of Welsh cultural nationalism. Civic nationalism in rejecting Welsh identity led as one always knew it would to the unchallenged arrivals of new British identities, besmirched with the most horrendous xenophobia and racism.