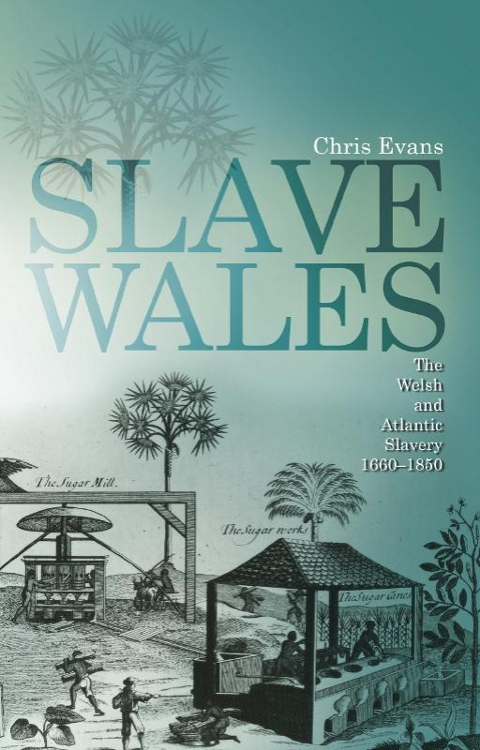

SLAVE WALES

Chris Evans, 2010

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing it in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the copyright owner except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Applications for the copyright owners written permission to reproduce any part of this publication should be addressed to the University of Wales Press, 10 Columbus Walk, Brigantine Place, Cardiff, CF10 4UP.

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-0-7083-2303-8

e-ISBN 978-1-78316-120-1

The right of Chris Evans to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77, 78 and 79 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Historians do not work alone. We rely upon the encouragement, bibliographical generosity and candour of others. Andy Croll, Neil Evans, E. Wyn James, Bill Jones and Gran Rydn have all helped here some going so far as to read the whole manuscript.

The sections of this book that deal with Welsh-made Negro Cloth have been improved by comments from Robert Protheroe Jones of the National Waterfront Museum and Ann Whitall of the National Wool Museum. Seth Brown shared his knowledge of US textile manufacturers who catered for slave markets without hesitation. Others have been equally quick to help with their knowledge of Cuba and Welsh-inspired copper mining there: Roger Burt, Mara Elena Daz, Jonathan Curry-Machado, Lucy McCann at Rhodes House, Ins Roldn de Montaud, Robert Protheroe Jones (once again) and Sharron Schwartz.

Needless to say, those who have assisted me bear no responsibility for the arguments that Ive made. Indeed, some are deeply sceptical.

Thanks also go to Bettina Harden and her co-workers at the Gateway Gardens Trust, the charity whose educational project on the links between Wales and slavery has been an inspiration. Grateful mention also goes to Nick Skinner of BBC Wales, whose invitation to participate in a programme on the 2007 bicentenary of the abolition of the British slave trade was the starting point for this book.

My research has only been possible because of the financial support offered by a number of bodies. Ive been lucky enough to enjoy research fellowships at the Institute for Southern Studies at the University of South Carolina and the Virginia Historical Society, both of which contributed to this book. Ive also been the beneficiary of research funding from the Historical Metallurgy Society and the Pasold Research Foundation. Above all, Ive enjoyed the consistent support of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences at the University of Glamorgan.

P. G. Wodehouse dedicated Heart of a Goof, his short story collection of 1926, to his adored step-daughter Leonora, without whose never-failing sympathy and encouragement this book would have been finished in half the time. This book is dedicated to Ellis and Dan with the same wry affection.

The Atlantic slave system was so vast and endured over such a long period of time that it has no one history. It is a tangle of histories. There are few points on the oceans circumference that did not feel the gravitational drag of slavery, but no two places felt it in the same way. Some locations participated very directly. They were the ports through which slaves passed or from which slave ships sailed. Some of these had a very prolonged involvement with the traffic in human beings. The export of slaves through Luanda on the Angolan coast, first documented in 1582, only ended in 1850. During those 268 years over 1.3 million men, women and children were embarked for the New World. Luandas history as a slave port was an epic of suffering that few other places could match.

Other places had a far more distant or tangential connection to the world of slavery. Some connections are completely unexpected. Gammelbo, a tiny land-locked community in central Sweden, may seem as far removed from Atlantic slavery as it is possible to be in Europe, yet every summer in the 1730s and 1740s workmen at its four forges set aside their normal work and turned to making iron bars of very precise dimensions. Precision was important because these bars were exported via Stockholm to Bristol, sold there to slave merchants and then shipped on to West Africa where this so-called voyage iron was used as a form of currency in slave markets. Just as some remote locations supplied commodities that could be exchanged for slaves, so others, even more distant, were recipients of slave labour. Black slaves first came to Peru in the 1530s with the Spanish conquistadors. By the end of the sixteenth century large numbers of Africans were being landed on the Caribbean coast of modern-day Colombia, trans-shipped across the Isthmus of Panama and then consigned to a second middle passage, over a thousand miles in length, down the west coast of South America. The ocean best known to the 20,000 Afro-Peruvian slaves living in Lima in 1640 was the Pacific, not the Atlantic.

Everywhere has a different tale to tell about the slave trade. Because the churning, slave-centred Atlantic economy was so immense it was also varied. It brought together regions that made highly specialised contributions. South-west Ireland, for example, became a major exporter of beef, butter and other salted provisions in the eighteenth century. The stimulus for Corks rise as a meat-packing centre was quite specific: it was the escalating demand for barrelled beef to feed slaves in the Caribbean. A similar story can be told of many places in the Atlantics hinterland (and some way beyond) that produced the things needed to buy slaves, or to feed them and clothe them. The fiercely salted beef of Munster joined linens from Silesia, muskets made in Lige, cottons from Gujerat, Clyde herrings, cachaa (the sugar-cane liquor of Bahia in Brazil) and much, much else besides in a huge swirl of commodities. The trade in Africans required them all.

So what of Wales? Direct involvement in the slave system in the sense of fitting out slave voyages was very limited. Wales was flanked by two of the largest slave ports in Europe Bristol and Liverpool but it is doubtful that a single slaving expedition left a Welsh harbour. (Not one of them had a merchant class of sufficient weight to raise the capital.) Nor did Wales contribute much in the way of maritime hardware to the slave Atlantic. A few Welsh-built ships did engage in the Guinea trade, but they were not many: just fourteen between the 1730s and the close of the legal trade in 1807. Of these, some made one-off contributions, like the Nancy, a 70-ton brig launched at Conway in 1755, which made a solitary venture into the trade. Departing Liverpool in July 1763, she was to land 131 Africans at St Kitts later that year. But what did this amount to? A good many individual ports did more. The fourteen ships that are known to have been launched in Welsh yards (there may be others, of course, among the many whose place of construction is never specified in the official record) are outnumbered even by those of Newport, Rhode Island. Indeed, the colony of Rhode Island, a patch of New England coastline only one-fifth of the size of Wales, built over sixty slave ships in the course of the eighteenth century.