Contents

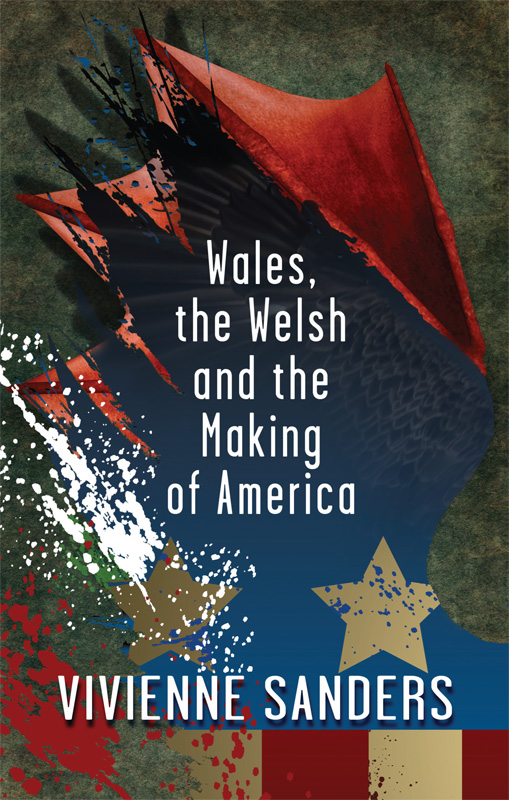

WALES, THE WELSH AND THE MAKING OF AMERICA

WALES, THE WELSH AND THE MAKING OF AMERICA

Vivienne Sanders

Vivienne Sanders, 2021

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing it in any medium by electronic means and whether or not transiently or incidentally to some other use of this publication) without the written permission of the copyright owner except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Applications for the copyright owners written permission to reproduce any part of this publication should be addressed to The University of Wales Press, University Registry, King Edward VII Avenue, Cardiff CF10 3NS

www.uwp.co.uk

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN: 9781786837905

eISBN: 9781786837929

The right of Vivienne Sanders to be identified as author of this work has been asserted in accordance with sections 77 and 79 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

The publisher has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for any external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, anddoes not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Cover design:Olwen Fowler / iStock

The Merion Friends: .

For my parents and Great Aunt Kitty,

who loved both Wales and America.

I CAN STILL remember my surprise during a tour of Shirley plantation in Virginia in 1970, when our guide said someone in colonial America hailed from a place in England called Wales. Although the early 1970s saw an outburst of white ethnic assertiveness and pride amongst groups such as Italian-Americans and Polish-Americans, Californian congressman Thomas M. Rees told the US House of Representatives in 1971 that very little has been written of what the Welsh have contributed in all walks of life in the shaping of American history. That statement remains true half a century later.

Why have Welsh and Welsh American contributions to American history been frequently underestimated or ignored? First, Wales is a small country, sparsely populated and long dominated by England and the English. Many Americans have been unaware of Wales or have thought it simply a place in England. Second, although a considerable proportion of colonial Americans were Welsh or of Welsh ancestry, they would soon be greatly outnumbered by immigrants from other nations. Dr Arturo Roberts, founder of a North American Welsh newspaper, pointed out: There are 20 people of Irish descent for every one with Welsh descent that makes a big difference. Third, the Welsh assimilated relatively easily. They bought into the American dream, said Professor John Roper of the American Studies department at Swansea University. As George Washington supposedly said, Good Welshmen make good Americans. Edward Hartmann, the son of a Welsh immigrant mother and writer of Americans from Wales (1967), argued that Welsh immigrants and their descendants were not chauvinistic over past wrongs or vengeance-minded over former ill-treatment, they came over quietly, modestly, willing to accept what opportunities the new environment might have to offer. A possible fourth reason might be the lack of any long-lasting and frequently replenished concentration of Welsh Americans in big cities there has been no Welsh equivalent of the Boston Irish. Much Welsh emigration took place before the United States became increasingly industrialised and urbanised during the nineteenth century, and those early immigrants tended to settle in small townships in rural areas.

There have been a few studies of the Welsh and America, notably the respected Welsh historian David Williamss pamphlet Wales and America (1945). Edward G. Hartmanns Americans from Wales was reprinted in 1978 and 1983, and then by the National Welsh-American Foundation (NWAF) in 2001. There have also been more specialised studies of the Welsh in areas such as the Pennsylvania coalfields, Iowa, Tennessee and Wisconsin. Overall, though, as Arturo Roberts noted, The Welsh have low visibility. Ronald L. Lewis, author of Welsh Americans: A History of Assimilation in the Coalfields (2008), used a similar vocabulary when he described the Welsh as nearly invisible to most Americans. Perhaps it is time to try to make the invisible visible, especially if doing so helps illuminate the nature and development of the United States of America.

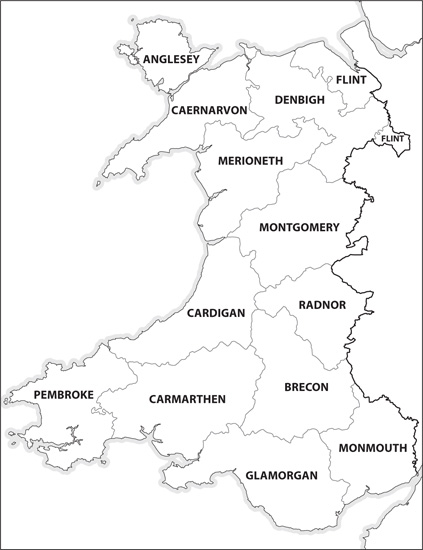

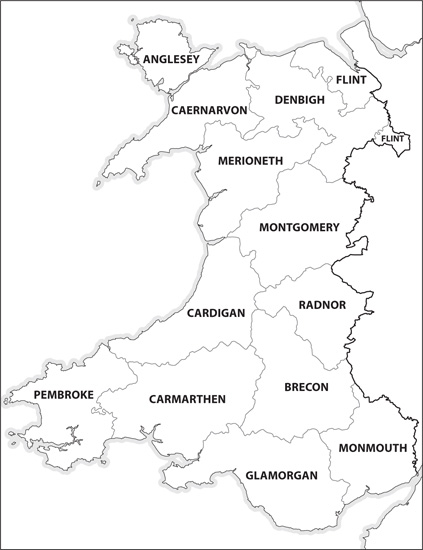

The old counties of Wales, as they were during the emigration of the Welsh to America during the seventeenth, eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. These county names were changed in the later twentieth century, but this book uses the names familiar to the Welsh emigrants discussed here.

THE NUMBER OF AMERICANS OF WELSH DESCENT

While 2.5 million Americans said they had Welsh ancestry in a recent US census, most of the 20 million who said they were simply Americans came from the South, to which many Welsh people had emigrated in the colonial period. As a result, the number with Welsh descent may well be greater.

I N 1979, I attended Professor Gwyn Alf Williamss inaugural lecture at Cardiff University. He was an unforgettable speaker with a distinctive appearance a white mane, piercing periwinkle blue eyes, the shortest of short Welshmen. His stutter guaranteed attentive and supportive listeners willing him to get the next word out, and his enthusiasm was contagious. Gwyn Alf was particularly inspired by his return home to Wales after years of exile in England, and he lectured on another Welsh wanderer, Prince Madoc. Legend had it that Madoc established a colony in North America in the twelfth century. A cynic warned me that my euphoria would wear off outside the lecture theatre, but it never did, and so I start with Madoc in attempting to argue Welsh importance in the making of America.

There is no physical proof that Prince Madoc ever existed, but legend has him as an illegitimate son of Owain, a ruler of Gwynedd in north Wales. A thirteenth-century Flemish work mentioned a seafaring Welsh Madoc, but it was in Elizabethan England that the Madoc legend gained great prominence. The first printed mention was in Sir George Peckhams A True Reporte (1583), which advocated colonisation and discussed who had lawful title to North America. The account of Madoc in David Powels The Historie of Cambria now called Wales (1584) was speedily taken up by other writers, notably such widely read promoters of English exploration and colonisation as Richard Hakluyt and Walter Raleigh.

The Elizabethan dissemination of the Madoc story arose primarily from the English desire to refute Spains claims to exclusive possession of the New World by right of Spanish-sponsored exploration and papal gift. Interestingly, one sixteenth-century Spaniard labelled what is now the Gulf of Mexico as Tierra de los Gales Land of the Welsh.