Table of Contents

David Douglass Travels in North America, 1824-34

PROLOGUE

NATURES HAND

On the last day of April, 1827, eight men worked their way up a snowy slope called the Grand Cot or Big Hill, the fi nal approach from the Columbia River to Athabasca Pass. Seven of the group plodded steadily up the steep pitch toward the Continental Divide, but one of their number, a sturdy young man wearing spectacles and leggings fashioned from the sleeves of an old capot, struggled mightily with a set of unfamiliar footgear.

Ascending two steps and sometimes sliding back three, the snowshoes kept twisting and throwing the weary traveler down (and I speak as I feel) so feeble that lie I must among the snow, like a broken-down wagon-horse entangled in his harnessing, weltering to rescue myself.

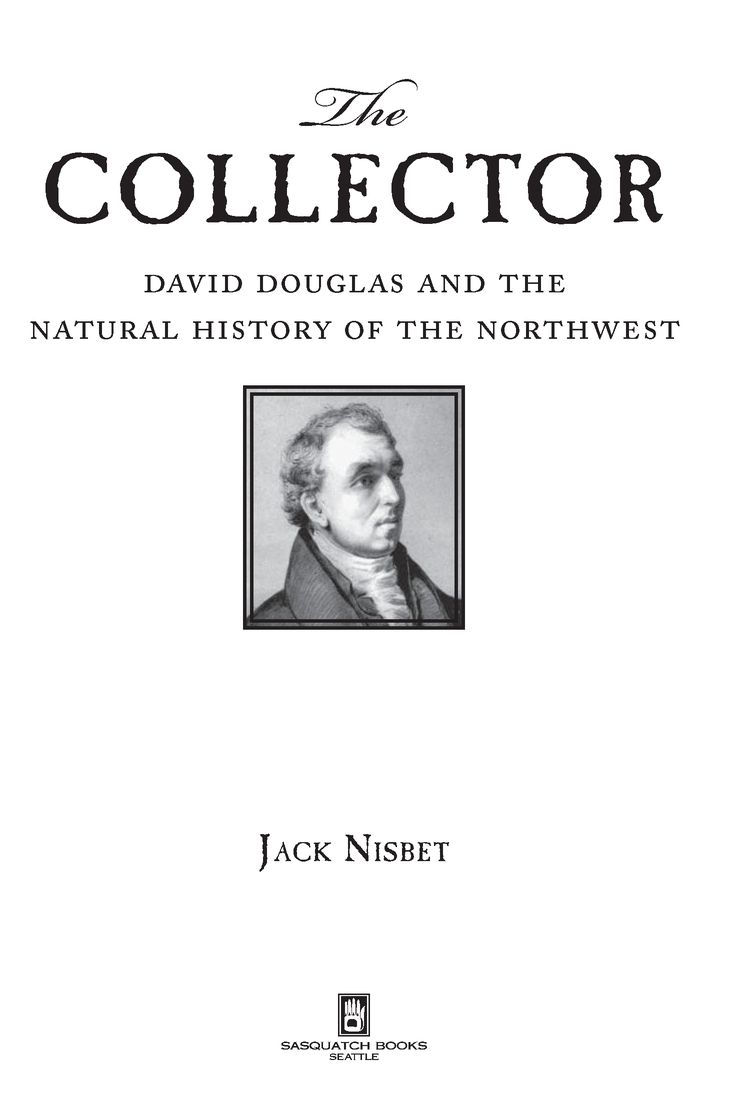

An oblong tin cylinder with rounded edges hung from a leather strap and bounced against his chest. This collecting box, or vasculum, identified the straggler as the Scottish plant collector and naturalist, David Douglas. The only member of the party not on the pay list of the Hudsons Bay Company, Douglas was on his way back to England after two years in the Northwest. During that time he had lost neither his self-effacing sense of humor nor his consuming interest in the world around him.

After making camp that evening and gathering dry twigs to start a fire, Douglas melted snow for tea and watched his companions perform their appointed taskstwo or three bringing in firewood, the rest flooring the house by piling soft fir branches on the snow. That night, sleeping atop the fragrant cushion with his balding head ensconced in a nightcap woven from the fleece of a mountain goat, he dreamed of being in Regent Street, London! Yet far distant. Regent Street housed the headquarters of his employers, the London Horticultural Society, who had sent him to this distant place to collect plants. Tucked inside his knapsack, carefully wrapped in oil-skin, a tin box held hundreds of small paper packets filled with the seeds of wildflowers and shrubs and trees that would transform the faces of gardens across Great Britain.

Awaking to find himself not in Regent Street but on a snow-covered slope of the Rocky Mountains, Douglas began the days routine: rise, shake the blanket, tie it to the top, and then try to see who is to be at the next stage first. When the small party crested the Divide and halted for their midday meal, agent Edward Ermatinger shot a male spruce grouse, the first of this curious species that Douglas had seen. He pored over its plumage and crown feathers, resembling a small well-crested domesticated fowl, then dissected its crop, which was stuffed with black conifer needles. He carefully preserved the birds skin to take home with him while Ermatinger roasted its flesh. Savoring the succulent meat for lunch, Douglas surveyed his surroundings. Unable to hide his excitement at finding himself upon the great spine of the continent, I became desirous of ascending one of the peaks, and accordingly I set out alone on snowshoes to that on the left hand or west side, being to all appearance the highest.

The saddle of Athabasca Pass was densely wooded, and Douglas often sank to his waist as he floundered through the corny spring snow. But the toil did not prevent him from plucking samples of a strange club moss to tuck inside the hinged lid of his vasculum. He bent to examine desiccated gentian flowers, and burrowed into drifts to taste frozen crowberries. When he reached timberline, the crustier snow of the open slope allowed him to make much better progress, until the surface abruptly changed to a mount of pure ice, sealed far over by Natures hand as a momentous work of Natures God.

Standing on a shoulder of the peak he later named Mount Brown, Douglas gazed at mountains as far as his eye could see, many of them higher and more rugged than the one on which he stood. Bright sunlight accented the colors of a large ice field below: the aerial tints of the snow, the heavenly azure of the solid glaciers, the rainbow-like hues of their thin broken fragments. An avalanche tore loose from a south slope to roar away with incredible velocity, producing a crash and grumbling like the shock of an earthquake, the echo of which resounded in the valley for several minutes. Although he began to wish that he had brought along his flint and steel to start a fire on the chilly heights, his emotions ran closer to ecstasy than to urgency. The sensation I felt is beyond what I can give utterance to, he later wrote.

He estimated that his ascent had taken five full hours, and the waning afternoon encouraged him to return with all possible speed. Back on the icy crust, he used his stiff snowshoes to great advantage: Places where the descent was gradual, I tied my shoes together, making them carry me in turn as a sledge... sometimes I came down at one spell 500 to 700 feet in the space of one minute and a half. Squeezing every ounce of awe from his toboggan ride down from the top of the world, he found himself back in camp after only an hour and a quarter. He did pay a price for his fun, however, and his journal entry the next morning was distinctly lacking in elevated prose. May 2. My ankles and knees pained me so much from exertion that my sleep was short and interrupted.

Yet the adventure had surely been worth it. As he lingered on the Continental Divide, Douglas would have been able to look west into the Columbia River drainage, his bailiwick for the past two years. He was well aware of the unique position he had held as he moved through the regions mosaic of communities. To the Hudsons Bay Company, this was the Columbia District, a place to carry on the business of trading for animal pelts. After the expedition of Lewis and Clark two decades earlier, David Douglas was the first visitor with the freedom to focus squarely on the regions natural history, and the first to range beyond the standard travel paths frequented by the fur traders.

He used this opportunity to gather plants at a furious rate, identifying new species with a particular eye for those that showed promise as garden ornamentals. But his interests extended far beyond foliage, and the journals stowed inside his knapsack bulged with descriptions of mammals, birds, fish, rocks, insects, fungi, and anything else that caught his attention. He recorded the activities of humans as well, weaving a portrait of life along the Columbia during the heyday of the fur trade.

When modern naturalists set out to study the flora and fauna of the Northwest, many of the names that roll off their lips and out of their field guides first flowed from the pen of David Douglas. From the mouth of the Columbia River to the crest of Athabasca Pass, he tied many of the first bright ribbons to mark the approach of Western science. Such names only hint at the depth of his accomplishments, however. Douglass story hurtles through landscapes that only he saw as new, but his finely textured accounts of the Northwest still shimmer against a place that, two centuries later, seems both familiar and drastically changed.