Copyright 2012 by Jack Nisbet

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form, or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published by Sasquatch Books

19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

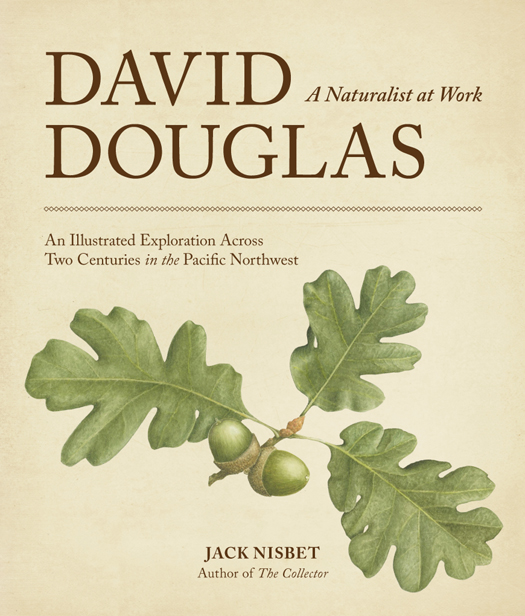

Cover illustration: Jeanne Debons

Cover design: Anna Goldstein

Interior design: Sarah Plein and Anna Goldstein

Interior design composition: Sarah Plein

Maps by Emily Nisbet

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

eISBN: 978-1-57061-830-7

Sasquatch Books

1904 Third Avenue, Suite 710

Seattle, WA 98101

(206) 467-4300

www.sasquatchbooks.com

Some portions of this book appeared, in different form, in Columbia magazine, We Proceeded On, American Surveyor, and in particular the North Columbia Monthly.

v3.1

This book is dedicated to people who work with plants of all persuasions.

Thanks to Steve and Karla Rumsey for their long-term dedication to a cause, and special thanks to Claire, Emily, and James.

This could not work without you.

CONTENTS

Prologue:

Work in Progress

I. Waters of the World:

Crossing the Columbia Bar

II. Going Their Own Way:

The People of the Northwest Coast

III. Awakening:

The Roots of Plateau Culture

IV. Science and the Company:

Outsiders in the Hudsons Bay Company Empire

V. Invisible Kin:

Mixed-Blood Families of the Fur Trade

VI. Comrades and Miscreants:

Bringing the Northwest to London

VII. The Forest and the Trees:

After the Fire

VIII. The Wise Economy of Nature:

Adapting to the Landscape

IX. The Iron Sphere:

Earths Magnetic Pulse

X. Travelers:

Riding the Wind

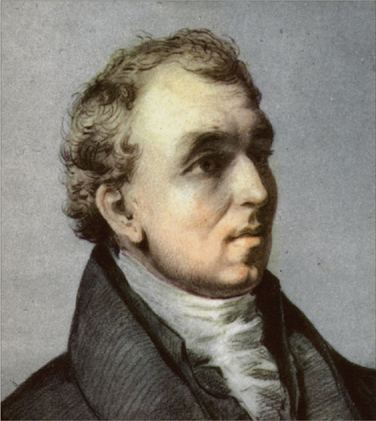

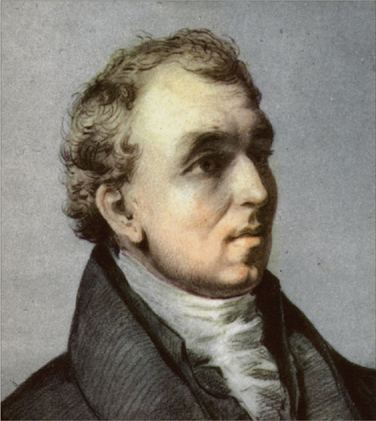

Portrait of David Douglas

Have you seen Douglas? I was greatly impressed by his intelligence and modesty.

Dr. Thomas Stewart Traill ()

LIST OF MAPS

Mouth of the Columbia River

Pacific Northwest Coast from Cape Disappointment to Grays Harbor

Hudsons Bay Company Interior Trade Houses

Hudsons Bay Company Posts, Pacific Northwest, 18251833

London, 18281829

Douglass Latitudes for California Missions, 18301832

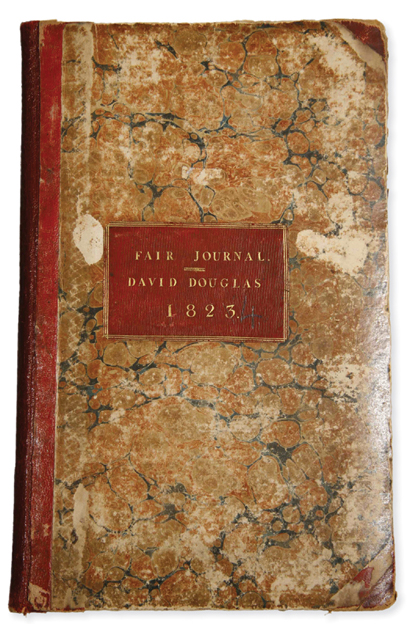

Journal from Douglass 1823 collecting trip to the mid-Atlantic ()

PROLOGUE

Work in Progress

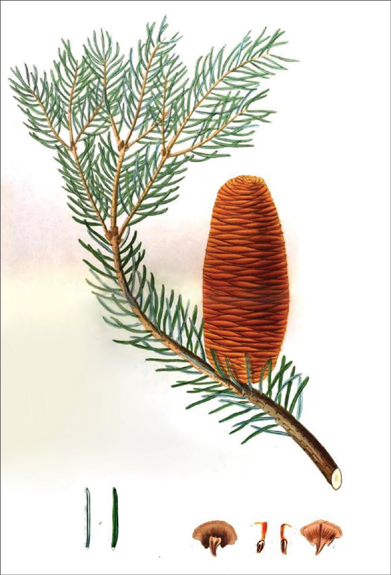

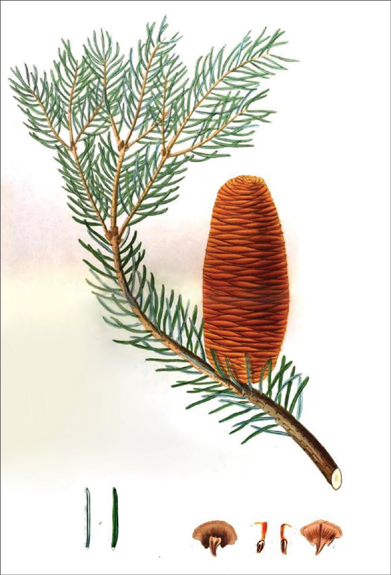

A tall splendid tree; leaves glaucous. The cones being on the top, I was unable to procure any. I went up one, but the top was too weak to bear me.

David Douglas, above Cascades of the Columbia, September 1825

THE CONES OF EVERGREEN TREESthe seeds of most greenery, when you think of ittend to grow at their most vibrant extremities. For members of the tribe of true firs, that usually means right at the crown. And since fir cones disperse their seeds by falling apart upon maturity, the only way to collect them at their moment of viability is to reach their exclusive domain. Thats why I am ascending a grand fir, Abies grandis, on this breezy afternoon in early fall.

Grand fir

Abies grandis

The bark of the young trees smooth and polished green, with minute round or oval scattered blisters, yielding a limpid aromatic fluid.

David Douglas ()

Grand firs hold the darkest, shiniest green needles in the forests of my home in the Inland Northwest. Double-ranked on gracefully downswept branches, their whorls make ready stairs, and each of my scraping attempts to find a good foothold pours waves of sweet balsam through the air. After the first few steps, however, the limbs of my chosen tree bounce unnervingly, and I move close against the smooth-barked trunk for security. Blisters of clear pitch pop against my stomach as I corkscrew around the trunk, grasping for holds that become shorter and more constricted as the foliage closes in.

By the time I can swing my head back and spot the crown, the trees leader is small enough to wrap a trembling hand around, and the top sways back and forth with each puff of breeze. On the uppermost star of foliage, a few small clusters of finger-length cones point to the sky. Each cone glistens with droplets of pitch that refract the late afternoon sun into shades of citrus green. Shoving through a last tangle of bristling new growth, I can almost touch them. Almost.

The leader seems entirely too thin to hold human weight, so I hug the tree for several minutes to consider the situation. My breath slows until it matches the easy metronome of the crown, until all my force flows downward through the trunk. That feels better. I wait, and slow my breath some more. On one forward swing I step up two whorls and stretch my arm to its limit, which is exactly enough to finger one gluey cone. I twist it delicately, as if it were a hot light bulb. When the cone resists, I unscrew it a fraction more.

Douglas squirrel

I procured some curious kinds of rodents which had been hitherto undescribed.

David Douglas ()

That brings a sound I have heard before, when stepping on a beetle barefooted at night. The cone disintegratesno, explodesin my hand. Brittle green sheaves, each one carrying a small fir seed, rain over my forearm. The pitch glues some of them to my sleeve. My forefinger and thumb close on a stringy central coreall that is left of my prize.

A second cone shatters the moment touch it. Unnerved, I retreat to my secure position and try to calm myself.

It is pleasant to be up here, rocking in the wind. As I stare at the glistening gems above me, I ponder how Scottish naturalist David Douglas reacted to this same situation on a similar fall day in 1825. After returning to the ground, he tried to shoot some cones down with a musket, but the tree was too tall. He thought of chopping it down, but his hatchet was too small. He concluded a journal entry about his futile attempts with a note on the elusive seed: Make a point of obtaining it by some means or other. And since Douglas was a persistent soul, within two years a London nursery was displaying grand fir seedlings sprouted from cones he had sent back to England.