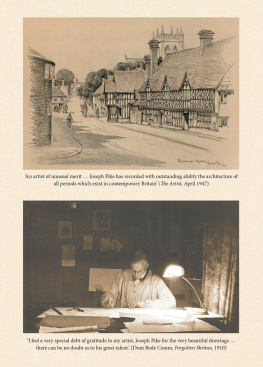

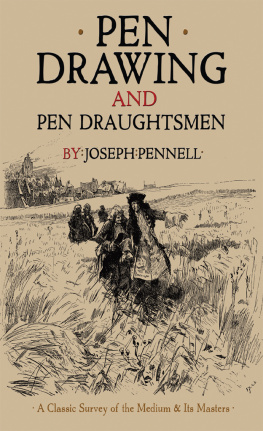

Joseph Pike has been described as an artist of unusual merit, who recorded with outstanding ability the architecture of all periods which exists in contemporary Britain. A master of the art of pencil drawing, he produced evocative sketches of old churches, and colleges, monasteries and modern offices, picturesque street scenes in historic towns such as Rugby and Chester, as well as a great number of London landmarks. His illustrations were commissioned by authors architects and publishers, reproduced in books and on postcards, sold as prints and exhibited on the walls of the Royal Academy.

When he died in 1956, the Catholic Herald referred to him as a distinguished artist, though not personally well known, and until the publication of this biography little has been written about his life and work. Joseph Pike: The Happy Catholic Artist reveals the man behind the art, beginning with his roots in Bristol and his education by the monks of Ampleforth Abbey, marking the beginning of a lifelong association with the Benedictines. Early attempts to launch a professional career as an artist were interrupted by military service in the First World War, and it was only through dogged determination and hard work that he managed to establish himself in the 1920s.

Although there is little explicit religious content in his work, Joseph Pike was a devout Catholic who worked with many of the leading figures in the literary and artistic revival that transformed Catholic culture in interwar Britain. This biography explores his friendships with the likes of Ronald Knox and Bede Camm, his work for the Benedictine monks of Caldey Island and the Dominican Friars in London and Oxford, and demonstrates how his artwork helped preserve the memory of the Catholic martyrs and forgotten shrines of historic England.

This is the story of a remarkable artist and quiet, modest man, hugely admired by his contemporaries, whose contribution to 20th century British art deserves greater recognition.

Joseph Pike

Joseph Pike

The Happy Catholic Artist

James Downs

Copyright 2018 James Downs

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers.

Matador

9 Priory Business Park,

Wistow Road, Kibworth Beauchamp,

Leicestershire. LE8 0RX

Tel: 0116 279 2299

Email:

Web: www.troubador.co.uk/matador

Twitter: @matadorbooks

ISBN 978 1788034 746

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Matador is an imprint of Troubador Publishing Ltd

The descendants of Joseph and Constance Pike

would like to remember

Barbara Mary Codrington (ne Pike)

Anthony Joseph Cyprian Pike

and

Margaret Anne Salmon (ne Pike)

We would also like to thank James Downs.

Words are not enough.

Contents

Illustrations

Introduction

In 1591 a young carpenter from Moordown in Dorset was hanged, drawn and quartered in Dorchester. William Pike had been converted to Catholicism by Father Thomas Pilchard, a native of Battle, Sussex, chaplain to the Catholic family of Arundell at nearby Chideock Castle. Although Pilchard had been executed in 1587 probably not long after Pike was received into the Catholic Church the priest had clearly made a strong impression. When the carpenter was asked to recant and save his life and family, he boldly replied that it did not become a son of Mr. Pilchard to do so.

This biography concerns the life of another Pike, also a Catholic from the West Country, whose illustrations for Bede Camms book Forgotten Shrines (1910) helped perpetuate the memory of the recusants and martyrs who adhered to the Catholic faith during the centuries of persecution. Places of religious significance were a natural choice for someone who had been educated in a Benedictine monastery and had two brothers serving as Dominican friars, yet such scenes represent only a part of the artists output. Joseph Pike known as Joe to family and friends produced a large body of work over four decades as a professional artist, including lively sketches of historic towns and cities such as Rugby, Chester and Stratford-upon-Avon, evocative views of lost corners of London and Bristol, atmospheric drawings of ruined abbeys and country churches, along with a rich variety of commercial illustrations for hotel brochures, company histories and sales catalogues. The fine detail and crisp lines of much of this work give Joes drawings a sense of precision akin to architectural drawing, which perhaps reveals the debt he owed to time spent working in an architects office. His sensitivity for the form and substance of stonework was perhaps best expressed in the monochrome tones of pencil drawings but he was equally effective when deploying colour: in addition to the attractive postcards produced to accompany his most popular commissions, he painted landscape scenes in oils, pastels and watercolours, as well as experimenting with lithography. Many of the media and processes used by Joseph Pike have fallen out of favour in our digital age, and an examination of his work provides a fascinating insight into the strategies employed commercial artists in the early 20th century to improve print quality, boost sales and enhance professional reputation. What is particularly interesting about his life and career is the way that he succeeded in connecting disparate cultural and religious strands; studying Joseph Pikes work in detail reveals a sense of unity in diversity, opening up new ways of understanding how the often-fraught relationship between artistic talent, commercial necessity and religious principles can flourish.

This was an artist who learned to draw in a monastery and whose lifes work was rooted in the piety and principles of Benedictine monasticism, and yet at the same time was highly-respected The Catholicism of Joseph Pikes art should not be sought in explicitly religious imagery or publications, because the popular artistic appeal of his illustrative style transcended narrow sectarian concerns, whatever the subject. It is found rather in the quiet industrious piety that permeated his work, dissolving the distinction between religious and secular, and refuting any lingering suspicion that Roman Catholicism was somehow un-English. It was a principle that would have resonated strongly with the martyrs and recusants of old, and one that was captured perfectly in an obituary printed under the heading The Happy Catholic Artist:

All his life Joseph Pike shunned publicity and hated advertisement. He was a very happy person happy in his work, happy in his home, happiest in his Church It would be in the tradition of other artists if, now that he is dead, collectors should seek eagerly for his work.

(The Catholic Herald, 10 August 1956)

Chapter 1

The Catholic Revival

In order to fully understand the relationship between Joseph Pikes faith, life and art, it is necessary to remember that the Catholic community in England was only just emerging from a dark period over which the Reformation still cast a long shadow. By the Act of Supremacy in 1535, King Henry VIII appointed himself Head of the Church of England and assumed all powers of jurisdiction over church doctrine, clergy appointments, rituals, revenues and lands that had previously belonged to the Pope. Over the next seven years his vice-regent Thomas Cromwell oversaw the dissolution of the monasteries by which all religious houses were disbanded. The Anglican Church took on a more Protestant character under Henrys son Edward VI (1547-53) before suffering a violent reversal under the rule of his Catholic half-sister Mary I (1553-58.) It was only under the long reign of Marys half-sister Elizabeth I (1558-1603) that a more moderate form of Anglicanism was established, retaining some external forms of Catholicism such as the episcopate while rejecting papal authority, and at the same time avoiding the extreme Protestantism practiced in Calvins Geneva. The Elizabethan Settlement was a strategic compromise, intended to accommodate diverse religious views and thus bring an end to the conflict and bloodshed of recent decades. The degree of religious tolerance this implied did not, however, extend to Roman Catholic beliefs and practices which would remain forbidden by law for over 230 years, apart from a brief respite under James II.

Next page