Also by Jim Downs:

Sick from Freedom: African-American Illness and Suffering During the Civil War and Reconstruction

Why We Write: The Politics and Practice of Writing for Social Change

Taking Back the Academy: History of Activism, History as Activism

Copyright 2016 by Jim Downs

Published by Basic Books,

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, contact Basic Books, 250 West 57th Street, 15th Floor, New York, NY 10107.

Books published by Basic Books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail .

Designed by Jack Lenzo

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Downs, Jim, 1973 author.

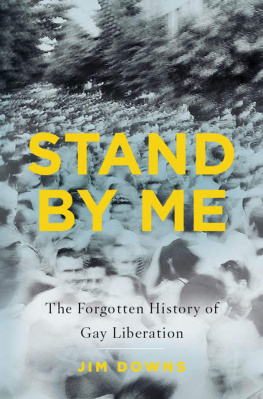

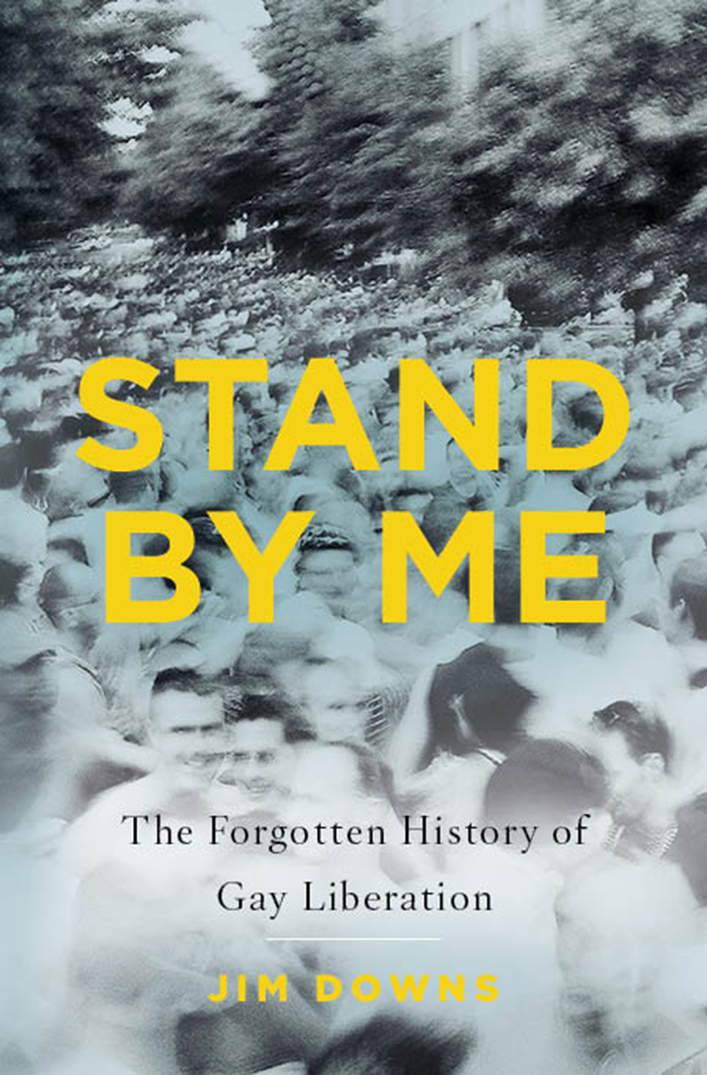

Title: Stand by me: the forgotten history of gay liberation / Jim Downs.

Description: New York: Basic Books, [2016] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015040030 | ISBN 9780465098552 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Gay liberation movementUnited StatesHistory. | GaysUnited StatesHistory20th century. | GaysPolitical activityUnited StatesHistory20th century. | Gay rightsUnited StatesHistory20th century.

Classification: LCC HQ76.8.U5 D69 2016 | DDC 306.76/6dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015040030

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For all those who stood by me

IN PROVINCETOWN, 1995

Bill Coyman

Jaimie Fauth

Jennifer Gannon

Jen Manion

Scott Paro

IN REHOBOTH BEACH, 19962001

John Bantivoglio

Dave Bornmann

Ross Buntrock

Joe Figini

Bobby Jasak

David McFadden

Rob OConnor

Douglas Warren Schantz

Jared Silverman

Ryan Walker

IN NEW YORK CITY, 20072014

Christi Helsel Botello

Shay Gipson

Geoff Lewis

Mike Montone

Christopher Stadler

Table of Contents

Guide

CONTENTS

This is what I remember.

There were boxes from floor to ceiling, overflowing with magazines, playbills, and photographs. Newspapers and books were stacked everywhere. I made my way to the back of the room, where I found a shelf made of egg crates and plastic bags containing more mysterious papers. I had been told that Tommi Avicolli, a gay activist from Philadelphia, donated a portion of the materials before he moved to San Francisco. My assignment was to go through his boxes and identify the contents.

I found that I became easily distracted. I would open a box and quickly find myself raptly reading a dusty newspaper, staring at the photos of men from the 1970s, some shirtless and muscular, others with long hair and pensive affects. I studied their faces and became mesmerized by their bodies. I dont remember what intrigued me more: that I was uncovering an unknown past, or that I was finding part of myself in the dust.

This was in the 1990s. I was in college, an English major. My best friend, who was a history major, encouraged me to come with her to the William Way Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Community Center in Philadelphia, located on a narrow cobblestone side street that resembled a back alley. She studied the past and understood the connections between the boxes in the centers archive and the lives that we ourselves were making twenty blocks away at the University of Pennsylvania. Unlike our university library, which remained open until midnight, seven days a week, the gay library and archive at the William Way Community Center could afford to stay open for only a few hours a week.

My friend took careful notes on yellow legal pads about the contents of the boxes she unpacked. I remember her standing amid the debris of the past, in command of the history that rose up to her waist. I remember hoping, as I sat on egg crates, that she would not see me reading instead of writing, memorizing the images instead of making sense of them.

This was part of the politics of gay history, my friend told me as we walked back to campus that day, past the gay bars and coffee shops. She explained that gay people had to collect their own history and tell their own stories because they couldnt rely on straight people to record their past. She reminded me that gay people were barely mentioned in the courses that we were taking.

She was politically fierce and intellectually formidable, but even while listening to her most compelling arguments, my mind would return to the photosto the images of the shirtless guys who appeared in ads in the old newspapers. She would sense me drifting. Thats why we are volunteering, she would remind me. So that gay history will not be forgotten.

Eventually I not only absorbed that message but became inspired by it. She and I and other friends of ours and gay people across the country had a responsibility to document the past and to tell our own history.

A newly minted history PhD, I was in line at the Tribeca Film Festival in New York City for the opening screening of a documentary, Gay Sex in the 70s. It was 2005, and gay liberation was over thirty years old, but in the city where it began gay culture was still surprisingly limited. There were the occasional gay documentaries and films that played at the independent movie houses. There were a handful of cable television series that portrayed gay characters and had gay-themed story lines. Most of the representations of gay life appeared in the gay neighborhoodson the covers of magazines in the coffee shops, on calendars showcased in card and gift storefronts, and on weekly events newsletters stacked at the entrances of gay bars.

That night the theater was packed, and some people even had to be turned away. Gay Sex in the 70s charted the rise of gay liberation. Men who had lived through the era were interviewed and recounted having had sex all the time. One man told how he worked from home but spent most of his day at a nearby cruising spot having sex with anonymous men. Another explained how easy and available sex was: All you had to do was walk down the street. Others told stories about sex in abandoned trucks along the Hudson River piers in the middle of the night, in the shrubs near the beach, at parties in vacation homes. Interspersed with the interviews were clips of crowded bathhouses, of discos that catered to well-endowed men, of semi-naked men groping each other. Life was a pornographic film, one of the interviewees explained. In the films narrative, gay liberation was the liberation of gay mens sexual urges.

Toward the end of the film, the tone began to darken and the disco music stopped. The talking heads on-screen now wore worried expressions. No one uttered the phrase free love. And then someone said it: AIDS. The outbreak of HIV, a virus that seemed to only infect gay men, would put an end to the rampant sexual activity that defined the 1970s. As depicted in the film, unrestrained sex had led, more or less inevitably, to the illness and death that accompanied the spread of HIV.

![Downs - How to make a simple pot still : [a step by step guide]](/uploads/posts/book/92548/thumbs/downs-how-to-make-a-simple-pot-still-a-step-by.jpg)