Consider: The Agricultural Revolution took thousands of years. The Industrial Revolution took hundreds of years. The Information Revolution is taking only decades. If we use the brains God gave us, we can perhaps now bring about the Non-violent Revolution. If we don't, this could be the last century for the human race.

Who knows, who knows? Technology may save us if it doesn't wipe us out first. In any case, the next few years will be the most exciting years any of us have ever known.

Maybe there's room to retell my parable of the Teaspoon Brigade. Imagine a big seesaw. One end is on the ground, held down by a bushel basket half full of rocks. The other end of the seesaw is up in the air with a bushel basket on it one-quarter full of sand. Some of us have teaspoons and are trying to fill it. Most people are scoffing. It's leaking out as fast as you put it in.

But we say, No. We're watching closely, and it's a little more full than it was. And we're getting more and more people with teaspoons. One of these days that whole seesaw will go zoop! in the opposite direction. People will say, Gee, how did it happen so suddenly?

Us and all our little teaspoons over thousands of years.

Keep in mind that we have to keep using our teaspoons, because the basket does leak. Are you in the Teaspoon Brigade?

Thank you, David, for your years of work. As Robert Burns put it, O wad some Power the giftie gie us to see oursels as ithers see us.

PREFACE

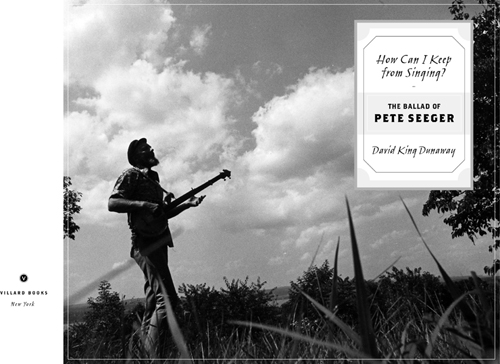

I ' M A LINK IN A CHAIN, PETE SEEGER VOLUNTEERS, IN A LONG American tradition of singing for reform. Abolitionists; union organizers; civil rights, peace, and environmental activistsall turned to song to make their points.

For music captures the soul in ways that few political speeches can; it has encouraged and inspired revolutions. Realizing this, governments have tortured musicians like Victor Jara in Chile and Mikos Theodorakis in Greece, hoping to destroy a song by silencing its composer or performer.

In the United States, investigations of composers take the place of thumbscrews. Pete Seeger and his popular quartet, the Weavers, in the fifties, have the distinction of being the only artists in American history formally investigated by the Senate for sedition and insurrection under Title 18, U.S. Code 2383-85.

No one is investigating Pete Seeger these days. At eighty-nine, he still lives with Toshi, his wife of sixty-five years, in a converted red barn in New York's Hudson River Valley. Though he once set Carnegie Hall vibrating with the sound of a thousand voices, he's beginning to give up singing.

Few recordings capture his way of uniting strangers in song, and few know all that his campaigns have cost him and his family the confiscated passports, the lost jobs, the personal attacks.

Pete Seeger's life resembles his song Abiyoyo, an African folktale he adapted. It's the story of a boy and his musician father, whom the town banishes for playing too loudly or too late at night. Then the Giant comes, and the boy defeats him. He doesn't fight him, exactly. Instead of a stone, he uses a ukulele.

The Giant dances until he's out of breath and falls down. Then the father whisks him away with his magic wand. The boy's music saves the town.

Now the town's elders can't remember why these great patriots shouldn't be at the head of the parade.

Come back, bring your damn ukulele! And the crowds welcome them and sing a song in their honor.

That Pete Seeger's father was run out of Berkeley's music department; that his son would bring his banjo to sing to his inquisitorsone doesn't need to know these things to decipher the parable. That music could help save a community from fascism or McCarthyism; that it's one of the forces uniting humanitythis has been Pete Seeger's belief all along.

IT'S A CHALLENGE to write about a complex man whose motto is Strive for simplicity, and learn to distrust it. The ideal biographer of Pete Seeger would be a musician and an ethnomusicologist, an activist and a sailor, a forest ranger, an archivist, and a political historian.

I'm not all of these things. I am not even sure I'm any of them. But a quarter-century ago I wrote Seeger's biography. When I began, Seeger cautioned me: This biography would not be authorized. He wouldn't read or censor the draft; he would cooperate with interviews and research.

In the past few years, I've consulted dozens of memoirs and histories published since this book came out. Besides the 120 interviews I deposited at the Library of Congress, I've talked with dozens more. Mostly, I've talked with Pete Seeger.

At the beginning of this century, at his request, we went through the book page by page. For three days we woodshedded reactions, corrections, and regrets. From the early morning sun till the last light off the river, we'd sit in the log cabin he'd built, until Toshi came out from the barn and tapped at the window for lunch or dinner. We'd eat awfully healthy meals of lentils and brown rice with miso or homemade garlic butter, and an occasional nod to his sweet tooth.

Pete Seeger's reactions are now laced throughout the book. His most frequent response was a dislike of the word career:

To most people that means making money and getting famous, and I was not concerned about this. I've lived with this terrible contradiction. If I splurge, if I go down and buy some fancy food I don't need, that's food that could keep somebody else alive. It's one reason that I didn't want to go into the music industry and make a lot of money, why I definitely didn't want to have a career with a capital C.

Now it's true, I could have become a violinistmy mother wanted me to. I could have become a businessman my grandfather wanted me to. I could have become a journalist; if I'd had more perseverance, I might have. If I'd had a grant early to be a researcher, I could have been one. But I wasn't willing to take the discipline. To be a real researcher, you have to get that degree and fulfill all the academic obligations.