To Sandrine

CONTENTS

Guide

This book explores the world I grew up in, and the first round of thanks goes a long way back: To Pete Seeger and Bob Dylan, both of whom profoundly influenced me, though Ive never met Dylan and had only a few visits with Seeger. To Dave Van Ronk, who taught me so much about music, writing, and life, and Eric Von Schmidt, the only person ever to hire me as a harmonica player. And to my parents, George Wald and Ruth Hubbard, who bought me records, took me to concerts, and immersed me in the political struggles of the 1960sthough, alas, they never took me to the Newport festivals.

I tried whenever possible to go back to primary sourcesrecordings, film, and writing from the periods I was coveringand was fortunate to have fuller access to some key sources than the myriad previous researchers who have covered much of this ground. In particular, I was able to hear clean copies of virtually all the Newport Folk Festival tapes, with guidance as to who appeared on every concert and workshop and what they sang, allowing me to correct and expand on previous descriptions not only of Dylans set but of performances by Seeger, Joan Baez, the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, the Chambers Brothers, Richard and Mimi Faria, and many others. The greatest pleasure of this project was being able to immerse myself for days on end in the incredible music at those festivals, and when I quote or describe a Newport performance without a citation in the endnotes, I am working directly from audio or film of the events, supplemented by background material from the deliberations and correspondence of the festival board. Most of the tapes were preserved by Bruce Jackson and are now available at the Library of Congress, where I owe special thanks to Todd Harvey, who also provided Alan Lomaxs files of Newport board meetings and correspondence; to Ann Hoog; and to Rob Cristarella, who digitized the tapes and explained sonic subtleties I would have missed. I was able to fill remaining gaps thanks to Fred Jasper at Vanguard/Welk Music, and I owe a special debt to Murray Lerner, whose films Festival! and The Other Side of the Mirror are matchless resources on Newport and Dylan, and who provided added context and access to footage of moments that were not caught on the audio tapes. Particular thanks (and a dinner in New Orleans) to Mary Katherine Aldin for her unique concordance to the Newport tapes and her infinite patience. Further thanks to Jeff Place, Stephanie Smith, Greg Adams, and everyone at Smithsonian Folklife, who guided me through Ralph Rinzlers files of Newport board minutes and correspondence and Diana Daviess photographs; Mitch Blank, Dylanologist extraordinaire, who welcomed me to his home and showered me with documents and recordings; and to all the people over the years who have preserved Dylans concert and interview tapes. Also to Jasen Emmons at the Experience Music Project for Robert Sheltons reporters notebook from the 1965 festival; Herb Van Dam for the scrapbook he and Judy Landers compiled that year; Ron Cohen, who once again opened his voluminous files on the folk revival; Steven Weiss and Aaron Smithers at the University of North Carolinas Southern Folklife Collection; Dave Samuelson for the Weavers electric session; Jeff Rosen, Todd Kwaite, Nick Spitzer, and Joe Carducci for passing along interviews with key figures; and all the helpful folks at the Tufts University Library, the Medford Public Library, and the Boston Public Library.

I am likewise indebted to all the people I interviewed or who answered my emailed queries, and I apologize to those who are not quoted: I favored period sources, which I often understood only because I had the chance to talk with people who were there, and some of the most helpful conversations did not end up in print. So equal thanks, in alphabetical order, to M. Charles Bakst, Jessie Cahn, Willie Chambers, Len Chandler, John Cohen, Jim Collier, John Byrne Cooke, Barry Goldberg, Bill Hanley, Jill Henderson, Bruce Jackson, Robert Jones, Norman Kennedy, John Koerner, Al Kooper, Barry Kornfeld, Jim Kweskin, Jack Landrn, Julius Lester, Raun MacKinnon Burnham, Janie Meyer, Geoff Muldaur, Maria Muldaur, Mark Naftalin, Tom Paley, Jon Pankake, Tom Paxton, Arnie Riesman, Jim Rooney, Mika Seeger, Betsy Siggins, Peter Stampfel, Jeffrey Summit, Jonathan Taplin, Dick Waterman, George Wein, David Wilson, and Peter Yarrow. Plus the many other people who were at Newport and added useful tidbits and insights, including Peter Bartis, Christopher Brooks, Dick Levine, Ann OConnell, Ruth Perry, and Leda Schubert.

Further thanks to everyone who provided hints, encouragement, and words of advice, including David Dann, Greg Pennell, Clinton Heylin, Ben Schafer, and all who responded to my attempts at Facebook crowdsourcing. I could not possibly name all of you, so please forgive my omissions. Among the unomitted, thanks to Peter Keane for many long and fruitful conversations and to Matthew Barton for reading through the manuscript and saving me from some grievous errors.

At the production end, I must first thank my wife, Sandrine Sheon (a.k.a. Hyppolite Calamar), who interrupted her clarinet studies to lend a hand with transcriptions of quotations, put up with six months of deadline panic, and employed her design skills to craft the photo insert. My redoubtable agent, Sarah Lazin, worked overtime to find this book a good home and confronted me with a difficult choice between several (thanks to Suzanne Ryan and Ben Schafer for understanding and continued friendship). Denise Oswald at Dey Street Books has been a consistently helpful, encouraging, and appropriately challenging editor. Heather Pankl quickly and reliably transcribed many of the interviews. Ben Sadocks copyediting saved me embarrassment and sent me on some interesting fact-finding missions, and his expansive knowledge of music and languages turned up some unexpected tidbits. Marilyn Bliss once again provided her admirable indexing skills. To all of you, and to everyone else who was supportive and helpful in this process, many, many thanks.

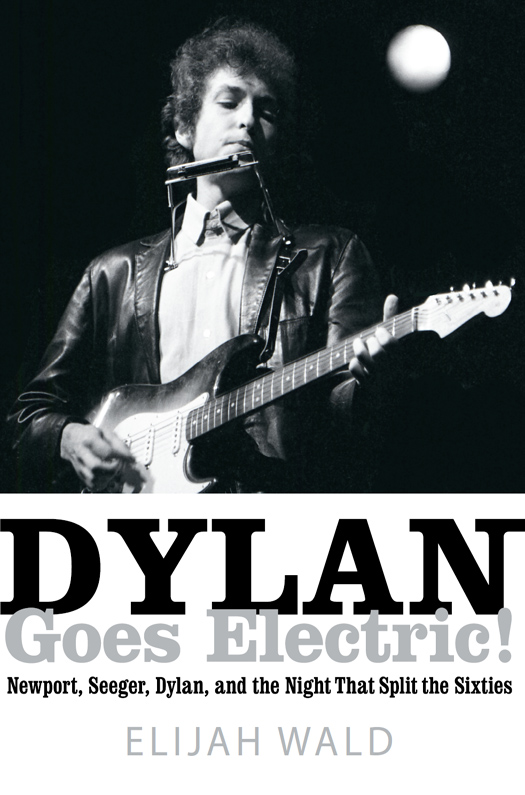

On the evening of July 25, 1965, Bob Dylan took the stage at the Newport Folk Festival in black jeans, black boots, and a black leather jacket, carrying a Fender Stratocaster in place of his familiar acoustic guitar. The crowd shifted restlessly as he tested his tuning and was joined by a quintet of backing musicians. Then the band crashed into a raw Chicago boogie and, straining to be heard over the loudest music ever to hit Newport, he snarled his opening line: I aint gonna work on Maggies farm no more!

What happened next is obscured by a maelstrom of conflicting impressions: The New York Times reported that Dylan was roundly booed by folk-song purists, who considered this innovation the worst sort of heresy. In some stories Pete Seeger, the gentle giant of the folk scene, tried to cut the sound cables with an axe. Some people were dancing, some were crying, many were dismayed and angry, many were cheering, many were overwhelmed by the ferocious shock of the music or astounded by the negative reactions.

As if challenging the doubters, Dylan roared into Like a Rolling Stone, his new radio hit, each chorus confronting them with the question: How does it feel? The audience roared back its mixed feelings, and after only three songs he left the stage. The crowd was screaming louder than eversome with anger at Dylans betrayal, thousands more because they had come to see their idol and he had barely performed. Peter Yarrow, of Peter, Paul, and Mary, tried to quiet them, but it was impossible. Finally, Dylan reappeared with a borrowed acoustic guitar and bid Newport a stark farewell: Its All Over Now, Baby Blue.