For Mike Seeger

I would not have been able to write this book if it had not been for Mike Seegers example and encouragement for so many years.

I would like to record my gratitude to everyone at Bob Dylan Music Company for their generous support and kind assistance in enabling me to quote from Dylans songs.

Thanks to my agent, Neil Olson, and my former editor at Harper-Collins, Elisabeth Dyssegaard, for their faith in this project from its inception, and to Jennifer Barth, my present editor, for her advice and support as the manuscript has made its way into print.

Special thanks go to all of my interview subjects, most of whom are named in the text; others were interviewed off the record.

I owe a debt of gratitude to all the previous biographers of Bob Dylan, and especially to the late Robert Shelton, and to Anthony Scaduto, and Larry Sloman. Michael Grays The Bob Dylan Encyclopedia is an extraordinarily rich resource, as are Clinton Heylins chronology A Life in Stolen Moments and his Behind the Shades Revisited. No living subject has as vast a historiography as this one, and as it increases in the decades to come scholars will be deeply indebted to these first generation biographies.

Some friends here in Baltimore and abroad have provided moral and material support. Above all I want to thank Jack Heyrman, a producer who provided books, tapes, and endless resources and helped with so many connections; Wall Matthews, a collector of Dylan materials and a musician who answered questions; Mac Nachlas, who provided records and discs just when they were needed; Olaf Bjorner and David Beaudouin, who did the same; Terry Kelly, of The Bridge, who was so supportive from the beginning, as were John Waters, John Paul Hammond, and Carrie Howland; Happy Traum, who welcomed me to Woodstock; Linda and Bob Hocking, who showed me Hibbing; Greg French, who led me through Dylans childhood home; and Nancy Riesgraf, curator of the Dylan collection in the Hibbing Library; Murray Horwitz and Ivan Mogull, who helped arrange interviews; Rosemary Knower, who read the manuscript and helped to shape it; and Jason Sack for editorial support.

I want to thank Jennifer Bishop, who kept the home fires burning during the hardest winter.

And then, of course, thank you again, Mr. Dylan, for rescuing my sister, Linda, when she was lost on a winter night in 1963, when all of us were very young.

Contents

PART I:

CHAPTER 1

CHAPTER 2

CHAPTER 3

CHAPTER 4

CHAPTER 5

PART II:

CHAPTER 6

CHAPTER 7

CHAPTER 8

CHAPTER 9

CHAPTER 10

PART III:

CHAPTER 11

CHAPTER 12

CHAPTER 13

CHAPTER 14

PART IV:

CHAPTER 15

CHAPTER 16

CHAPTER 17

PART I

CHAPTER 1

The frail-looking young man with tousled brown hair entered the auditorium from stage left, strumming his guitar while people were still getting settled in their seats.

A triple row of folding chairs had been hastily arranged in a semi-circle upstage behind the performers spot to handle the last-minute overflow. Now these latecomers were sitting down, applauding as he passed them. He wore a pale blue work shirt, blue jeans, and boots. It was as if he had come from some distance and had been singing all the while to himself and whatever group he could gather on street corners and in storefronts, his entrance was so casual and unheralded.

He moved toward his spot center stage next to the waist-high wooden stool. On the round seat was a clutter of shiny Marine Band harmonicas. Scarcely acknowledging the applause, mildly embarrassed by it, he lurched toward his place onstage wearing a steel harmonica holder around his neck that made him look like a wild creature in harness, blinking at the floodlights, hunching his shoulders to adjust the guitar strap that held the Gibson Special acoustic high on his slender body.

He was in our midst before we knew it and already performing. He stood and strummed. The houselights dimmed but remained on. The applause that began from the spectators behind him was warm but brief because we did not wish to interrupt the singer or miss any of his words. He sounded the simple melody on the mouth harp. The song he chose to sing first was unfamiliar but it was an invitation promising familiarity, like so many old ballads where the bard invites folks to gather round so he can tell them a tale: Come all ye fair and tender maidens, or Come all ye bold highway men.

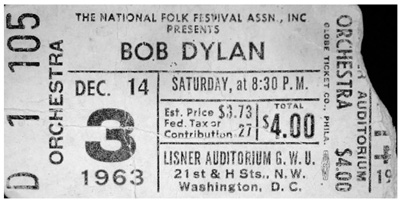

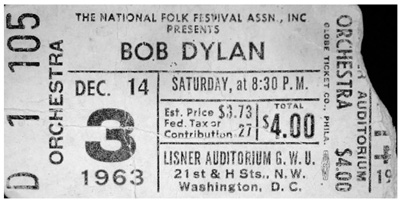

There were fifteen hundred seats in the sold-out Lisner Auditorium of George Washington University that night in December, and fewer than half of those were taken by college students. The steeply banked rows were filled with the faithful members of the Washington folk music community. The concert in fact had not been sponsored by the university but by the National Folk Festival, founded in the 1930s with the support of Eleanor Roosevelt and the novelist Zora Neale Hurston. Men in goatees or full beards, wearing plaid lumberjack shirts, dungarees, and horn-rimmed glasses, sat shoulder to shoulder with long-haired women in peasant blouses with ban-the-bomb buttons; scholarly types in tweed or corduroy jackets with leather elbow patches; a few middle-aged beatniks in black turtle-necks. There was more philosophy than conscious style, in boots and sandals, a rejection of button-down fashion and shoelaces that cut across generations during the Cold War.

My sister, Linda Ellen, age thirteen, was probably the youngest person in the building. My best friend, Jimmy Smith, and I had just turned fifteen and could not legally drive so my mother, thirty-seven, had driven us from the Hyattsville, Maryland, suburbs down Connecticut Avenue to the edge of campus, Twenty-first and H streets, N.W., to hear Bob Dylan in concert. She had purchased our seats in advance at the box officeshe always got the bestand so now we sat in the center of the fifth row, close to the lip of the stage apron, a few feet above and not ten yards away from Bob Dylan. When he finally stopped blinking and opened his eyes to the audience we could see how blue they were.

We heard the guitar first, a powerful sound that was percussive, modal, and clarion. He was strumming a full G chord with a flat pick in moderate tempo, 3/4 time. What made it distinctive and commanding was the force of the first stroke of the measure, and that the guitarist had added a high D on the second string to make a perfect fourth with the G next to it. That was the trick, the special magic that transformed the chord from a simple major triad to a mystical, ancient strain, Celtic perhaps, medieval or Native American, a mood transcending time.

Come gather round people, wherever you roam

And admit that the waters around you have grown

And accept it that soon youll be drenched to the bone.

This was a call to the barricades if not to arms. It was a reveille, a wake-up to the living and dead and the half dead that

Next page