M y aim has been to tell Dylans story through his voice and in the words of those closest to him. Books by the following authors have therefore been vital resources: John Malcolm Brinnin, Dylan Thomas in America; Daniel Jones, My Friend Dylan Thomas; Caitlin Thomas with George Tremlett, Caitlin: A Warring Absence; Aeronwy Thomas, My Fathers Places; Gwen Watkins, Portrait of a Friend and Cracking the Luftwaffe Codes.

In addition to these, I have found Andrew Lycetts Dylan Thomas: A New Life to be the most scholarly biography on which to rely for factual information and to fill in the gaps. Also valuable have been Heather Holts Dylan Thomas the Actor; David N. Thomass two volumes of edited transcripts of interviews by Colin Edwards and Constantine Fitzgibbon, Dylan Remembered Volumes 1 and 2; The Life of Dylan Thomas by Constantine Fitzgibbon; Dylan Thomas, the Collected Letters, edited by Paul Ferris, and his biography Caitlin; and archive material from the Dylan Thomas Society (thedylanthomassocietyofgb.co.uk). Dylans agents, David Higham Associates, have been very kind in allowing me to reproduce so much of his writing. I have used the following editions: Collected Poems 1934-1953, 2000; Collected Stories, 2003; Under Milk Wood, Definitive Edition, 2000, all by Orion Books; and Miscellany, 1963, Dent & Sons for the BBC broadcasts Return Journey and Reminiscences of Childhood.

I am very grateful to all the people closely associated with Dylan and his friends who granted me interviews and/or provided me with source material, especially Hannah Ellis, his granddaughter, and Trefor Ellis, his son-in-law; also Glenys Cour, Valerie Dawson, Mel and Rhiannon Gooding, Andrew Gordon of David Higham Associates, Fiona Green, Bruce Hunter, Ceri Levy, Desmond Morris, Cathy and Rob Roberts, Michael Rush of the Dylan Thomas Trust, Jeff Towns and Gwen Watkins and her family who kindly also gave permission to reproduce work by Vernon Watkins.

I am also grateful for access to interviews with my late father by Professor Tony Curtis in Planet magazine and Welsh Artists Talking, and by Dr Ceri Thomas in Cambria magazine.

Other sources include the BBC, the Daily Telegraph, The Guardian, The Independent, poemhunter.com, The Poetry Foundation, South Wales Evening Post, Swansea City Archive (and Dr David Morris in particular), Texas Quarterly, The Times and yorku.ca/caitlin/kardomah/ (for Charles Fisher).

My thanks are due to Graham Matthews for use of his excellent photographs of my fathers work, and also to the staff of the Glynn Vivian Art Gallery, National Museum and Art Gallery of Wales, National Library of Wales, the Dylan Thomas Centre Archive, Bernard Mitchell, Gabriel and Leonie Summers for their co-operation in sourcing images. Kirstin Sinclair took the photograph of me on the jacket.

No modern biographer can go without thanking all the creators and users of digital platforms and social media, often strangers, but who lead to new information, resources and news. Andrew Dally of @DylanThomasNews is essential reading in this respect (how wonderful Dylan Thomas would have been on Twitter). And finally, for their encouragement, patience and professionalism, heartfelt thanks to everyone at the Robson Press and especially Jeremy Robson; and to my family and friends Andrew, Alex and Suzi Pozniak, Ross Janes, Cat Brown, Professor Anne Murcott.

Hilly Janes

London, March 2014

CONTENTS

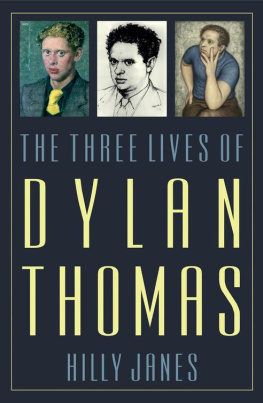

D ylan Thomas had many faces, but few people knew them as well as the artist Alfred Janes, my late father Fred as he was known to family and friends. Over the course of the poets short 39-year life, Fred painted his portrait three times hence the title of this book. The first was made in 1934 when Dylans first book of poems was about to be published, the second nearly twenty years later in 1953, the year that he died in a New York hospital. Ten years later Fred made a posthumous drawing of his friend to coincide with the first full-length biography of the poet, whose reputation was by then legendary, and not always for the right reasons.

With these three portraits as its anchor, The Three Lives of Dylan Thomas tells the story of three very different stages of Dylans life and afterlife, from the 1930s, when he was a highly promising teenage poet, to his rock star-like status as a performer in the 1950s. Finally, and unlike most other accounts of his life, it reveals what he left behind not just his tremendous literary output and its financial rewards, but the impact of his early death on his family and friends. Sixty years after Dylan Thomas died, his ghost is still a powerful presence in the lives of many people.

He was a drunken, hell-raising, womanising sponger. The description has been repeated so many times by countless associates and acquaintances that he has become a mythical creature. Readers who are looking to put flesh on the bones of that Dylan Thomas may be disappointed by this book. It aims, in the centenary of his birth, to put forward a different point of view through the words and images of the people who were closest to him the writers, artists and musicians that he grew up with in his hometown, Swansea, and his close relatives. And of course of Dylan himself, not only in his poetry, but his short stories, plays, broadcasts and letters. No one would deny that Dylan drank too much and that he could be a troublesome drunk, or that he slept with a lot of women and was a charming flirt. But Dylan was rarely the seducer, as even his wife Caitlin pointed out. He relied heavily on the generosity of these close friends, but they understood the difficulties of making a living from the arts, especially in an industrial town in south Wales ruined first by the Great Depression and then by Hitlers bombs. Dylan rarely, if ever, took advantage of people who were as badly or worse off than he was.

Fred recognised the ugly side of Dylan Thomas of course; they were close friends for more than twenty years. But he also saw many other faces of the poet at close quarters. There was the sixteen-year-old dropout with a masterly knowledge of English literature thanks to his father, an English teacher who taught both boys and whose study at home was lined with books that Dylan devoured. At the house of a mutual school friend, Daniel Jones, a brilliant student of English and music, Fred discovered Dylans gift for wordplay, sense of rhythm and appetite for making mischief, as well as a flair for acting and mimicry the qualities that made him such sought-after company in the pubs and clubs of Londons Fitzrovia. When Fred went to study portraiture at the Royal Academy Schools in London and Dylan later moved in with him, they shared digs with Mervyn Levy, another artist from Swansea who first met Dylan at junior school. Fred witnessed their shared love of creating hilarious fantasy characters and surreal stories that could go on for days. He also appreciated Dylans compassion for down-and-outs and the victims of the burgeoning fascist movement in 1930s London. And he saw what many people missed how tremendously hard Dylan worked, writing and rewriting with enormous dedication and craftsmanship.

At Dylans home in Cwmdonkin Drive in Swanseas genteel suburbs, Fred discovered the power the young poet could wield over an audience when he read his work aloud, and he listened, spellbound. Sometimes they would be in the company of another young Swansea poet whom Dylan had got to know, Vernon Watkins. These friends and their wider circle in Swansea discussed their ideas, stimulating and nurturing each other in a town that was more interested in chapel and commerce than paintings and poems. They were all successful on their own terms, producing poetry, stories, plays, radio and TV broadcasts, orchestral music, paintings and books on art that were underpinned by technical mastery and a fiercely independent mindset. Their achievements were recognised far beyond provincial Wales, and while none of them became as famous as Dylan Thomas, they became painfully aware of how his rackety celebrity lifestyle ruined his health, wrecked his family life and contributed to his early death.