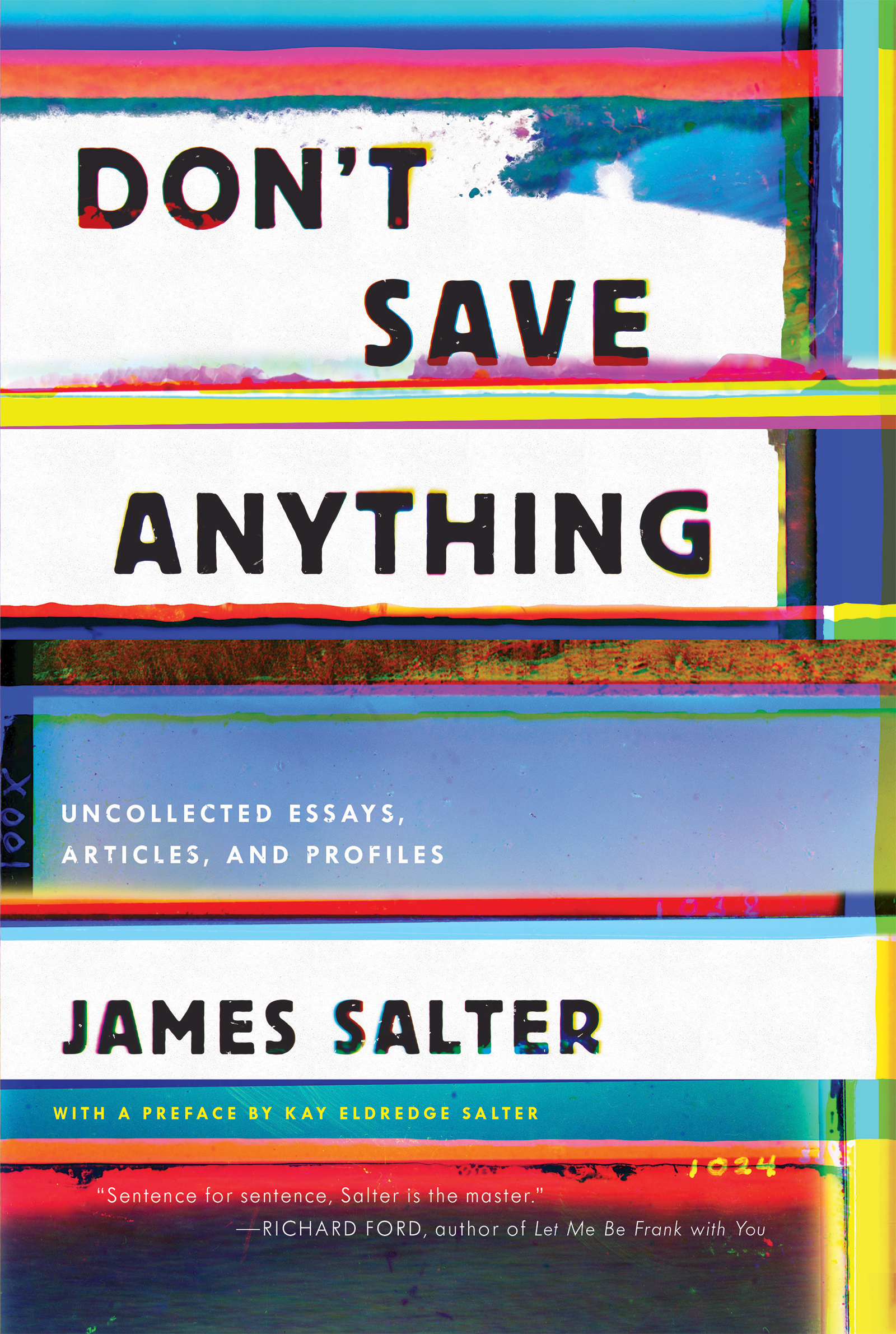

The Works of James Salter

The Hunters

The Arm of Flesh

A Sport and a Pastime

Light Years

Solo Faces

Dusk and Other Stories

Still Such

Burning the Days

Cassada

Gods of Tin

Last Night

There and Then: The Travel Writing of James Salter

Life Is Meals: A Food Lovers Book of Days (with Kay Eldredge)

Memorable Days: The Selected Letters of

James Salter and Robert Phelps

All That Is

Collected Stories

The Art of Fiction (with an introduction by John Casey)

Dont Save Anything

Copyright 2017 by The Estate of James Salter

Preface copyright 2017 by Kay Eldredge Salter

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Salter, James, author.

Title: Dont save anything : uncollected essays, articles, and profiles / James Salter.

Other titles: Do not save anything

Description: First Counterpoint hardcover edition. | Berkeley, CA : Counterpoint Press, 2017.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017017393 | ISBN 9781619029361

Classification: LCC PS3569.A4622 A6 2017 | DDC 818/.5409dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017017393

Jacket designed by Zoe Norvell

Book designed by Mark McGarry

COUNTERPOINT

2560 Ninth Street, Suite 318

Berkeley, CA 94710

www.counterpointpress.com

Printed in the United States of America

Distributed by Publishers Group West

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Preface

Boxes kept surfacing. Id forgotten there was so much. It was after Jims death at ninety, in June 2015, that I began to go through the many boxes of papers, most in obvious places. I gradually found others tucked away and then discovered still more boxes stored in places I could only get to with a ladder.

He used to advise, Dont save anything. He was talking about phrases or names or incidents a writer might be reluctant to use, holding them instead for a possible later work. But in a practical sense, he had clearly saved everything, not only finished copies of all hed published but also all his notes and drafts.

Much of Jims work appeared in collected volumes while he was aliveexcerpts from both his fiction and nonfictionabout life as a pilot in Gods of Tin , his travels in There and Then , the correspondence in Memorable Days with a man he came to know first through letters, and the short stories in the PEN/Faulkner winner Dusk and Other Stories and, later, Last Night . And of course, theres his memoir Burning the Days . In it he wrote about only ten of the many people or experiences or eras he might have chosen, taking as his guide the filmmaker Jean Renoirs quote: The only things that are important in life are the things you remember. That had been the structure, too, of his novel Light Years .

Years before that had been his decision to commit his life to writing. He said it was the hardest hed ever maderesigning from a promising career in the Air Force where hed spent over a dozen years, first at West Point and then as a fighter pilot in the Korean War. Only thirty-one and a lieutenant colonel, he turned his back on it to focus his hopes and energy on writing. He did it encouraged by his first published novel, The Hunters , based on his experiences in Korea, and on the sale of the book to the movies for a film starring Kirk Douglas.

Jim was married, with two very young daughters. He had an Air Force pension. He joined the reserves out of nostalgia, to get out of the house, and for the pay. He tried selling swimming pools. He and a friend made documentary films, even one that won a prize at Venice, called Team, Team, Team .

In the meantime, he was writing, trying to convince himself that he could really do it. His second novel was a derivative homage to William Faulkner. Decades after it was published, he rewrote it, unwilling to let it stand in its original form, and renamed it Cassada.

In 1961, when the Berlin Wall was built overnight to divide the city, Jim was recalled and sent to Europe. Out of that, he wrote a third novel, A Sport and a Pastime . It was the first book that was what hed imagined it might be and that finally allowed him to believe in himself as a writer.

At the beginning of the 1970s, Robert Ginna, the first editor-in-chief of People magazine, invited Jim to write for it. The subjects included serious writers, and Ginna sent Jim to Switzerland, France, and England to interview Vladimir Nabokov, Graham Greene, and Antonia Fraser. It would be Jims first journalism.

As I reread the published pieces, I remembered the stories that Jim told over dinner of all that had happened. The interviews had been arranged before his arrival in Europe, but suddenly everything fell apart. Greene had seen a spoof of People called PeepHole and avoided their meeting until a note from Jim, slipped under the door of Greenes Paris apartment, brought him around. Their talk produced not only the article for People but a bonus: Greene arranged for Jims novel Light Years to finally be published in Britain.

Then on to Montreux and the hotel where Nabokov and his wife Vera lived. But when Jim telephoned to confirm his appointment with her husband, Vera Nabokov told him he had to submit his questions in writing. Jim explained hed done that and had received no answer. Her husband wasnt well, she said. Still, shed ask him about doing the interview. Jim expected her to merely pretend to ask, then return to the phone to say Nabokov couldnt do it. Instead, she specified the next day and a time they could meet, warning Jim that he could take no notes or record any of the conversation. The two men hit it off, and Nabokov even proposed a second julep, as he called their drinks. But Jim regretfully rushed to the station to catch his train back to Paris. He missed the train and instead sat down with a notebook to feverishly scribble down everything Nabokov had said, telling himself that if Capote could claim to have remembered every word of a night with Marlon Brando, surely he could recall an hour with Nabokov.

Every story Jim wrote had a backstory. When he researched the development of the artificial heart, he went to dinner at the home of its inventor, Robert Jarvik, who decided to cook naked and insisted that Jim also jettison his clothes. Jim wrote about Robert Redford when Redford was still relatively unknown, the two men traveling together in search of material for Jims screenplay for Downhill Racer . Jim had imagined a character like Billy Kidd at the heart of the film, but Redford had a different idea and singled out a young skier who looked a lot like himself: Spider Sabich. The film still plays on late-night television, generating residuals that can almost buy lunch, as Jim liked to say. Redford became a star with Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid and remained a friend. When Jim received the lifetime achievement award at The Paris Review annual gala in 2011, Redford gave the keynote speech.

Jim also wrote about the lure of the movies. Dazzled by the European filmmakers of the 60s, he was asked to write films himself and even directed one called Three that starred the young Charlotte Rampling and the equally young and then unknown Sam Waterston. The experience convinced Jim he never wanted to direct again, but he wrote other screenplays until, with hopes of leaving writing more lasting, he eventually gave up all involvement in film to concentrate on what mattered most to himnovels and storieswhile still writing occasional journalism and essays.

Next page