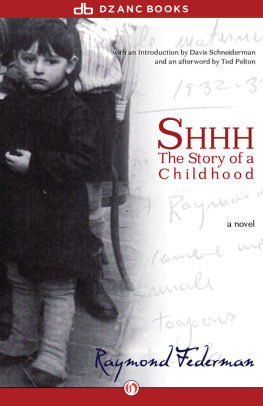

S HHH

S HHH

THE STORY OF A CHILDHOOD

R AYMOND F EDERMAN

All rights reserved, including without limitation the right to reproduce this ebook or any portion thereof in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of the publisher.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, events, and incidents either are the product of the authors imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, businesses, companies, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Excerpts from this book were previously published in American Book Review and Vice. Starcherone Books thanks the editors of these publications, as well as Joshua Cohen for his editorial assistance, and Steve Ansell for technical assistance.

As Federman Used to Say by Ted Pelton previously appeared in The Brooklyn Rail and was excerpted in American Book Review.

This publication is made possible with help from taxpayers of the state of New York, through the New York State Council for the Arts.

Copyright 2010 by Raymond Federman

Cover design by Rebecca Maslen

Cover photo of Raymond Federman, circa 1932-33. In photo on page 249 of members of Federman family, Raymonds mother Marguerite is standing on right. Both courtesy of the authors family.

978-1-4804-5799-7

Dzanc Books

1334 Woodbourne Street

Westland, MI 48186

www.dzancbooks.org

Distributed by Open Road Integrated Media, Inc.

345 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10014

www.openroadmedia.com

For Simone

The last Federman

Introduction

After the death of Raymond Federman, we always have SHHH

Davis Schneiderman

SHHH is a still point.

SHHH is a silence.

SHHH: The Story of a Childhood, Raymond Federmans last new novel, is a silence bequeathed by his mentor Samuel Becketteven before the creator of Molloy and Malone of Hamm and Clov changed tense in 1989. The works of the two writers, Beckett expatriated to France, and Federman, a generation later, expatriated to America, share the same absurd existential laugh, but also, in SHHH, the same emptiness. Whereas Becketts insularity, his cruelty, his end-of-times-in-a-jar inkblot joie de vivre (yes joy!) kept itself hidden within the entropic cylinder of Raymonds favorite Beckett work, The Lost Ones (1971), Federmans laughter-ature, his Joycean joco-seriousness, manifests in an alternate vision of literary stillness.

SHHH, in this regard, is anti-manifest destiny: its not a movement toward the frontier, but a movement toward the story that can never be told, but now, at the end of Raymonds career, must be attempted. From his first novel, Double or Nothing (1971) through the sequel of sorts, Take if or Leave It (1976), through his science fiction, his poetry, his criticism, and his later works which dwell again explicitly on the story of his life told again and againmost recently Aunt Rachels Fur (2001), and Return to Manure (2006)the multi-volume story of the writer Federman as the character Federman (and later Moinous and Namredef and the rest) suggests never the promise of continuity but rather the shock of recognition in the untellable. Federman, a character, introduces himself to us in Double or Nothing as the avant-garde writer, decades after the events of SHHH, involved in absurd typographical gambits.

Since then, Federmans work has largely abandoned the typographical pyrotechnics, yet has continued to reject the strain of melodramatic realism that SHHHs questioning meta-narrative voice repeatedly worries might be attributed to SHHH by the casual reader. Rather, this is a book built on equally evasive anti-qualitiesabsences and omissionsan incomplete series of vignettes blown apart by the events of a history that can never be told in a straight line. Even the subtitle, the story of a childhood, escapes the specificity of the first article. This may be the storybut it is only the single story of a childhoodone of many possible childhoods that the reader familiar with Federmans work knows he delights in articulating. It is (the character of) Federmans childhood yes, but only one version:

When they said Raymond, I heard my mother say quickly, Hes not hereFederman writes in SHHHand I know nothing of what happened to Simon, Marguerite, Sarah, and Jacqueline Federman, after the police truck leftFederman writes in SHHHand I know that they died in the gas chambers of Auschwitz. Auschwitz that fucking wordFederman writes in SHHHand Federman Yes? What? NothingFederman also writes in SHHH.

SHHH is not then the story of what happened to this character called Federman before his mother pushed him into the closet on July 16, 1942, the day the Gestapo took his parents and his two sisters away and they went to the camps never to returnas it is the story of the word SHHH and what this word on the page might mean when kept like a secret stillness for a lifetime lived after these events. Perhaps it took Federman so long to write this book, a book that moves backwards in time from the story that begins with Double or Nothing with the protagonist(s) in America after the war, because unlike the physical and textual manipulations of the page in that wild novel, SHHHthe word itselfis not an obviously funny word.

Federman is not writing his way out of the story of his life or finally giving voice to the important events of his boyhood. Rather, in SHHH, Federman is stopping, quieting, creating a final swirl of mad meta-textuality just as Alice upsets the banquet table at the close of her Looking Glass adventure. The power of those two famous Lewis Carroll tales two rests not in their symbolic significance, their literary arabesques, but in their literal and visceral moments. Federman, without stopping, takes us down a rabbit hole and into a looking glass world.

Stuffing himself on noodles in Double of Nothing, that older Federmanian narrator is like Prousteverything moves out from the tiny closet of his childhood. The world explodes from his typewriter turned at untoward angles. Every syllable speaks in an erotic openness. The Federman of SHHH, younger by decades, moving back to the moment of the closet and the unrelatable swirling cacophony of his early years, professes vignettes that cannot tell us of life before La Grande Rafle in July 1942, but rather, only how emptying a chamber pot, spending a year in Argetan, or being asked to suck his cousins cock become defamiliarized in reference to everything that may or may not have happened later.

Accordingly, the typed manuscript of SHHH is punctuated by odd spaces between paragraphswide gulfs in meaningsometimes even between the start and the close of sentences that seem impossible to finish. Ted Pelton, Raymonds publisher for this book and his other Starcherone titles (The Voice in the Closet [new edition], My Body in Nine Parts, and The Twilight of the Bums), attributes this to technical glitches caused by Raymonds word processing program; yet rather than fully correct these gulfs, rather than close the spaces between sentences and paragraphs and so reunite the text, we have observed these spaces in large part when they speak to this version of Federmans story; we have respected the silences the pauses the nothing-points that mean as much in a story such as this one, as their absences, the absences of these absences, might mean in another.

Next page