HARVEST HOUSE PUBLISHERS

EUGENE, OREGON

All Scripture quotations, unless otherwise indicated, are taken from The Holy Bible, New International Version, NIV . Copyright 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc. Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

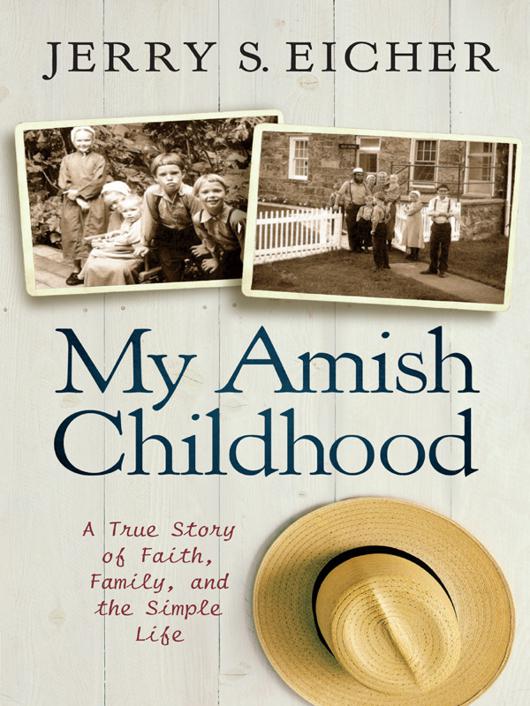

Cover photos Neil Wright

Cover by Garborg Design Works, Savage, Minnesota

MY AMISH CHILDHOOD

Copyright 2013 by Jerry S. Eicher

Published by Harvest House Publishers

Eugene, Oregon 97402

www.harvesthousepublishers.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Eicher, Jerry S.

My Amish childhood / Jerry S. Eicher.p. cm.ISBN 978-0-7369-5006-0 (pbk.)ISBN 978-0-7369-5007-7 (eBook)1. Eicher, Jerry S.Childhood and youth. 2. Eicher, Jerry S.Religion. 3. Eicher, Jerry S.TravelHonduras. 4. AmishOntarioBiography. 5. AmishHondurasBiography. 6. Authors, American20th centuryBiography. I. Title.PS3605.I34A3 2013818'.603dc23

2012028996

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, digital, photocopy, recording, or any otherexcept for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher.

Two books were used to help me keep the dates straight. I owe a thank you to Monroe Hochstetler for his book Life and Times in Honduras and to Joseph Stoll for his book Sunshine and Shadow . Any errors in dates or events in My Amish Childhood are my own.

Contents

I can still see his face. Lean. Determined. Framed by his lengthy beard. I can see him running up the hill toward our house. He was carrying his bag of doctor implements.

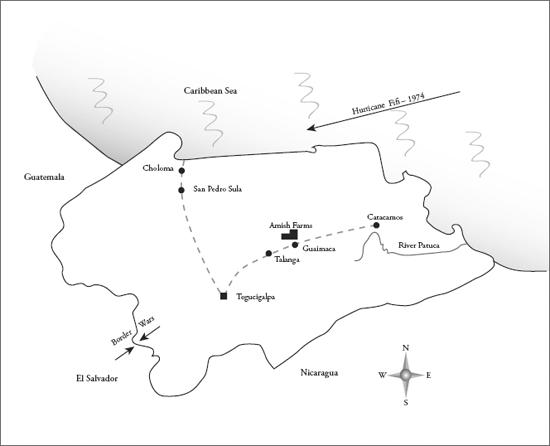

Mom was having chest spasms, and any real doctor was miles awayacross four hours of the broken, rutted, dusty Honduran road we took only as a last resort.

The running man was my Uncle Joe. The smart one of the family. The older brother. The intellectual genius. When Uncle Joe walked by, we stopped talking and listened intently when he spoke. On this day, he rushed by, not paying any attention to us children.

I knew he was coming about Mom, but I recall experiencing no fear for her life. Perhaps I wasnt old enough to have such a fear. To me, Uncle Joes haste seemed more entertainment than emergency. After all, Mom had looked fine to me a few minutes earlier.

When Uncle Joe left the house some time later, he issued a favorable report that I never questioned. Nor did anyone else. The mysteries of the Englisha world of medicine were even further removed from us than the four hours to town. Uncle Joe studied the books, and we trusted him.

Years later, when our little Amish community in Central America was on its last legs and held in the grip of terrible church fights over cape dresses, bicycles, singing in English or Spanish on Sunday mornings, and other horrors that the adults spoke of with bated breath, it was the look on Uncle Joes face as he talked with Mom and Dad by the fence on Sunday afternoon that made things clear to me. If Uncle Joe thought something was over, then it was over.

Uncle Joe lived below us, across the fields, in a house smaller than ours even though his family was much larger. How they managed, I never thought to wonder. Their house never looked crowded. It was kept spotless by his wife, Laura, and their oldest daughters Rosanna and Naomi. We didnt visit often on Sunday afternoons. Mostly we children dropped by on weekdays, sent on some errand by Mom or we wandered past on our meanderings around the countryside.

They kept goats in the yard, all of them tied with long ropes to stakes. One of them was named Christopher. We didnt have goats. Dad ran a machine shop, and Mom took care of the garden. Goats were foreign to us. Smelly creatures. Mom scorned goats milk, even when Uncle Joe said emphatically it was far superior to cows milk.

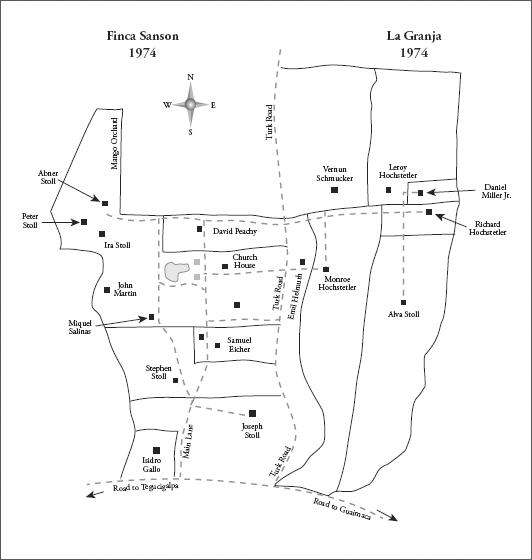

We all lived near each other in those dayspart of a grand experiment to see if the Amish faith could survive on foreign soil.

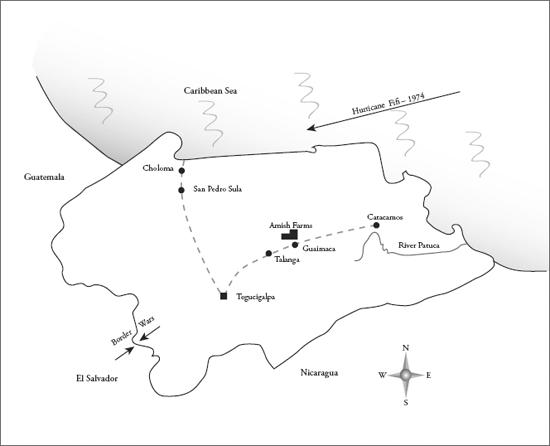

My grandfather, Peter Stoll, an Amish man of impeccable standing, had taken it upon himself to lead an Amish community to the Central American country of Honduras. He wasnt an ordained minister, and I dont remember seeing him speak in public. Still, the integrity of his life and his ideas so affected those around him that they were willing to follow him where few had gone before.

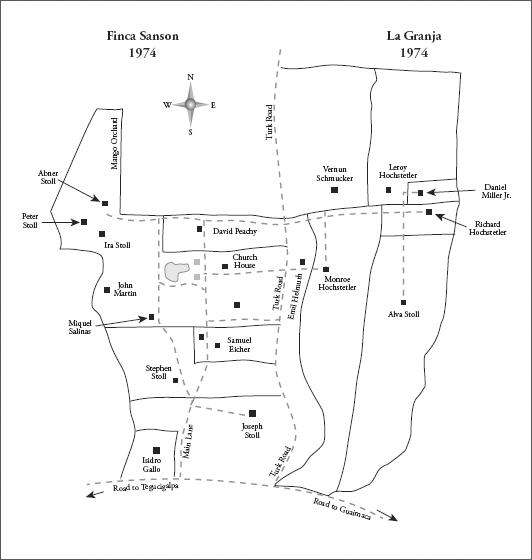

At the height of the experimental community, we ended up being twenty families or so. We all lived on two neighboring ranches purchased in a valley below a mountain. Most of us had come to Honduras from the hot religious fervor of the small Aylmer community along the shores of Lake Erie in Southern Ontario or from the detached coolness of Amish country spread over Northern Indiana. Plans were for the two to become one in mind and heart. And for awhile we did.

Those were wonderful years. The memories of that time still bring an automatic gathering of hearts among the Amish who were thereand even some of us who are no longer Amish. All these years later, most of us are scattered across the United States and Canadaexcept for the few of the original group who stayed behind.

Some of the people credit the joy of those days to the weather in our Honduras valley. And lovely weather it was. Balmy. Hardly ever above ninety or below forty. Others credit the culture. Some attribute our happiness to being so far from the States that we only had each other. I dont know the full reason for our happiness. Perhaps it isnt possible to know. But I do remember the energy of the placeits vibrancy. I do know the years left their imprints on us all.

This was my childhood. Those hazy years when time drags. When nothing seems to come soon enough. And where everything is greeted as if it had never been before. To me that landthat valleywas home. I absorbed it completely. Its sounds. Its language. The color of the dusty towns. The unpaved streets. The pigs in the doorway of the huts. The open fires over a metal barrel top. The taste of greasy fried beans. The flour tortillas and meat smoked to perfection. In my heart there will always be a deep and abiding love for that country.

Around us were mountains. To the north they rose in a gradual ridge, coming in from the left and the right to meet in the middle, where a distinctive hump rose into the airofficially named Mt. Misoco. But to us it was simply what the locals called it: La Montaa. The Mountain. Our mountain. Which it was in ways we could not explain.

To the south lay the San Marcos Mountains. At least thats what we called them. Those rugged, jagged peaks lying off in the distance. I never climbed those mountains, but I often roamed our mountainor rather our side of itfrom top to bottom. On its peak, looking over to the other side, you could see lines and lines of ridges running as far as the eye could see.

A party of courageous Amish boys, along with a few visiting Amish youngsters from stateside, once decided to tackle the San Marcos Mountains. They threw their forces together and allowed two days for the trip. I was much too young to go alongand probably wouldnt have anyway. But I waited for news of their adventure with interest. They came back soon enoughdefeated and full of tales of dark jungles and multiple peaks that disoriented the heart. No one even caught sight of the highest point, let alone the other side.

Next page