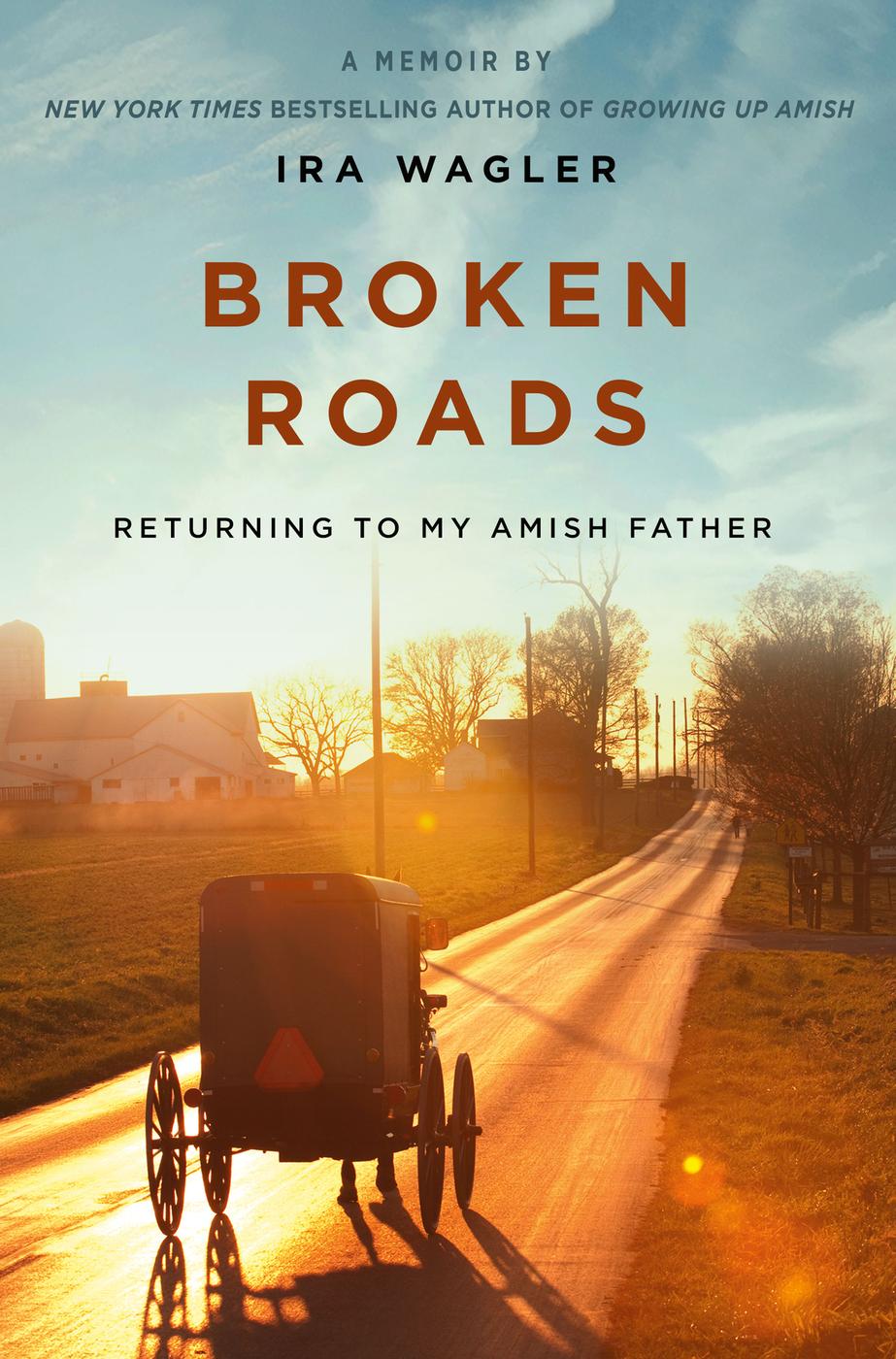

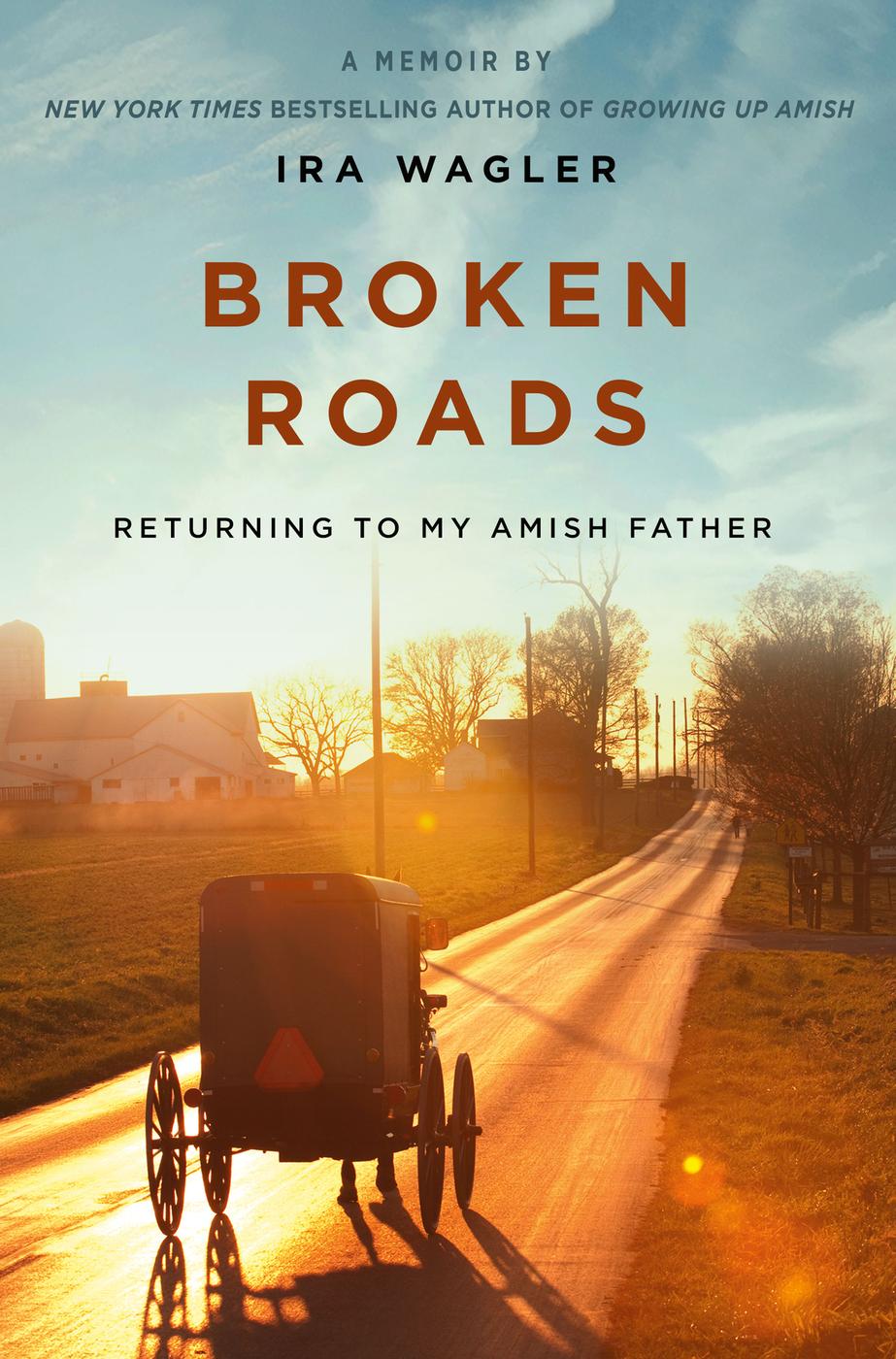

Copyright 2020 by Ira Wagler

Cover design by Jody Waldrup

Cover photo by Peter Ptschelinzew/Getty Images

Cover copyright 2020 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Some content is based on Ira Waglers blog at www.irawagler.com

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

FaithWords

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

faithwords.com

twitter.com/faithwords

First Edition: May 2020

FaithWords is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The FaithWords name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Wagler, Ira, author.

Title: Broken roads : returning to my Amish father / Ira Wagler.

Description: New York, NY : FaithWords, 2020.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019049242 | ISBN 9781546012061 (trade

paperback) | ISBN 9781546012054 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Wagler, Ira. | Exchurch membersAmish

Biography. | FathersDeath. | Wagler, David.

Classification: LCC BX8143.W22 A3 2020 | DDC 289.7092 [B]dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019049242

ISBN: 978-1-5460-1206-1 (trade paperback), 978-1-5460-1205-4 (ebook)

E3-20200323-DA-NF-ORI

This book is dedicated to my father, David L. Wagler.

He was a giant among his people.

Explore book giveaways, sneak peeks, deals, and more.

Tap here to learn more.

To lose the earth you know, for greater knowing; to lose the life you have, for greater life; to leave the friends you loved, for greater loving; to find a land more kind than home, more large than earth

Whereon the pillars of this earth are founded, toward which the conscience of the world is tendinga wind is rising, and the rivers flow.

Thomas Wolfe

The Amish have been around for a long, long time. Hundreds of years. Today, around three hundred and thirty thousand of these incredibly unique people are scattered throughout the United States and Canada. Out of seven-plus billion people in the world. For such a small group, they have a tremendous presence in English societynot only in North America but globally. They are much romanticized, but thats not their fault.

I was born one of them. Ira Wagler, the ninth of eleven children of David and Ida Mae Wagler, who emerged from the remote and rather despised Amish community in Daviess County, Indiana. I was the fifth son of a fifth son. My parents fled Daviess, as Dad was convinced the place was going bad. He didnt want to raise his family there. So I grew up among my people in smaller communities. It was a long hard road, to break away. I guess Im the one who remembers and who talks about things a lot, things that happened long ago. I wrote the story of my journey in my first book, Growing Up Amish, published in 2011.

Until my father and a few of his peers launched Pathway Publishers in the 1960s, the Amish never had much of a voice of their own. With Family Life magazine and the other Pathway publications, that voice was presented in a coherent structure for the first time. It was an extraordinary achievement. Nothing like that had ever been attempted before. My father and his peers had a vision and pursued it. With unceasing labor, at great financial risk, and with potential loss of prestige. The venture succeeded beyond their wildest imaginations.

They published a lot of good, solid stuff, especially on historical subjects, and common-sense articles on farming and other issues of specific interest to the Amish. And yet I have always felt that the fictional writings and op-eds published by my father and others at Pathway were less than honest. Too much gooey mush. Too didactic. Too pat. Too formulaic and predictable. All the same answers, all the time. All the loose ends neatly tied up in a little package for the reader to remember.

Maybe they were projecting a moral ideal they knew was impossible. I think they were trying to live that ideal, too. To present themselves and their community as an example. But its impossible to be perfect. You cant be a shining city on a hill by proclaiming your own greatness and glory. And real life isnt a nice little list of neatly packaged formulas, either. Never has been. Never will be.

Over the years, I have wondered many times if my father and his contemporaries ever questioned the path they chose. The God they served. Did they ever despair that He exists? Question their faith? Or was it always cut and dried, black and white? When their children left and they cut them off cold, did it not tear at them deep inside? The hard, ruthless laws of shunning, did they ever think twice about them? And wish it were not so? Did they ever struggle with such issues? Or did their harsh, cold facades truly reflect their hearts?

I like to think they struggled sometimes. Werent so sure of themselves. It would have been human. But I dont know that. Because they never told us. Maybe they thought it would show weakness. It wouldnt have. To the contrary, it would have shown strength. And honesty.

And I think, too, of my grandfather, Joseph K. Wagler. My fathers father, a man I never met. Because he died when my father was young. What kind of man was he? Ill never know. Nothing was ever told, other than the vacant, shallow depictions of a stern, godly father and deacon in the church. There is so much more I wonder about. How he looked. The man he was in the community. As he labored in the fields among his children. The sound of his voice when he prayed the morning prayer and read Scripture aloud in church. What gave him joy? And what were his quirks?

And my great-grandfather, Christian Wagler, who shot himself in the chest back in 1891 when he was thirty-six years old. His destitute widow remained, and his young sons and daughters. Christian was buried as a lost soul, there in the Stoll graveyard in Daviess County, Indiana. They knew, the Daviess people, that he was damned to burn in the fires of hell for all eternity. They knew, too, that the shameful stain of his suicide would haunt his seed forever.

Who was Christian? There are no photos. How did he look? Tall or short? And the demons he faced, in the dark recesses of his tortured soul, that finally overwhelmed him. Why did he do it? How was his last morning? What were his last words?

Ill never know. I can only conjecture, because no one ever honestly wrote the details at the time. And I accept that. Its who they were. Some things were just not done. Some layers not peeled back, the dark secrets carefully guarded. The old way, of the old generations.

But they left us poorer for our lack of knowledge of who they were. And who we are. Every culture and every generation brings forth its giants and its common people. Its common stories. Its tragedies. And its epics. But the characters involved cannot be seen and will not be heard and will be forgotten if no one speaks their names.

![Beverly M Lewis] - The Beverly Lewis Amish Heritage Cookbook](/uploads/posts/book/96304/thumbs/beverly-m-lewis-the-beverly-lewis-amish-heritage.jpg)