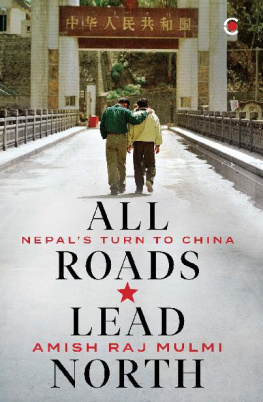

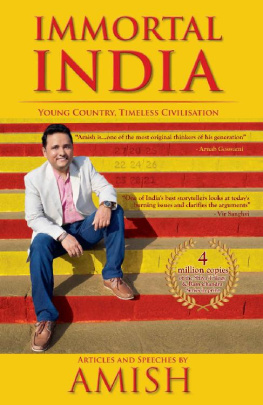

First published by Context, an imprint of Westland Publications Private Limited, in 2021

1st Floor, A Block, East Wing, Plot No. 40, SP Infocity, Dr MGR Salai, Perungudi, Kandanchavadi, Chennai 600096

Westland, the Westland logo, Context and the Context logo are trademarks of Westland Publications Private Limited, or its affiliates.

Copyright Amish Raj Mulmi, 2021

ISBN: 9789390679096

The views and opinions expressed in this work are the authors own and the facts are as reported by him, and the publisher is in no way liable for the same.

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher.

I n the winter of 1898, Sylvain Lvi, a French Indologist, trundled up the steep mountain passes that connected the plains of Nepal to the Kathmandu valley, the capital, in a palanquin and with sixteen bearers. Levi was by then accomplished in the field of Indology, but he had always wanted to study Nepal, for he believed the country had been at a crossroads of South, Central and East Asian influences throughout its history.

Levi left Calcutta on 8 January 1898, and after changing three trains, disembarked at Sugauli, the site of the 1816 treaty between the Gorkhas and the East India Company. Five days later, he arrived at the summit of Chandragiri, the 2,500-metre hill that overlooks the entire Kathmandu valley from the south. Everywhere at the further end and on the slopes are the villages and cultivations and east to west above the encircling mountains, a continuous lines [sic], uninterrupted, without a breach, of white snow peaks. Here they are quite close, three or four valleys to cross and beyond on the other side, Tibet, a piece of China, Cest le Tibet, un morceau de la Chine .

At the time, Nepal was ruled by Rana Prime Minister Dev Shamsher, now accepted as among the more liberal-minded Ranas to rule the country. Within the first week, Levi was taken to court and questioned about his knowledge. [Dev Shamsher] speaks to me of the Sakuntala in French. He asked me if I believe in the devas. By the end of it, the prime minister instructed his men to assist Levi in his search for manuscripts and inscriptions.

Over the three months he would stay in Kathmandu, Levi would note with derision the sanitary habits of the people who lived in the valley (But if ones eyes are opened ones nose must be closed. Kathmandu deposits her filth in her courtyards instead of her sewers.) He was a product of his times, carrying the impress of imperial superiority that was the hallmark of colonial explorers.

Leaving Kathmandu in March 1898, he would publish Le Npal: tude historique dun royaume hindou (Nepal: Historical Study of a Hindu Kingdom) between 190508, a magnum opus that continues to guide modern scholars on Nepali history. Despite previous works by European scholarsincluding Brian Hodgson, the legendary naturalist-cum-British resident in KathmanduLevis study stood out in one particular respect: he incorporated the historical views of Nepal through Tibetan and Chinese documents, going back all the way to the Tang dynasty annals from the seventh century CE . This was hitherto unknown in scholarship; Nepal had been viewed through the lens of India, as an offshoot of its dynastic histories or Indian cultures, and little attention was paid to its interactions with Tibet and China; a view that dominates popular discourse around the country even today.

Levis view of historyas an evolving process influenced by several factors and culturesis unfortunately less popular in the subcontinent, with history viewed through a linear and nativist lens as popularised by British colonialists. Imperialists often saw their subjugation of the subcontinent as a natural result of historical affairs, one which sought to bring civilisation to Your new-caught, sullen peoples/half devil and half child, as Rudyard Kipling wrote in The White Mans Burden. Quasi-imperialist views dominate modern discourses as well, best illustrated by the Indian medias imagination of Nepals modern-day relationship with China. Consider its coverage in the aftermath of the May 2020 IndiaNepal dispute over the Kalapani road, and its firm belief that the only reason Nepal could have objected to the road is because China asked it to. Beyond the ridiculous and sexist falsehoods about the Nepal prime minister being honey-trapped by the Chinese ambassador, headlines such as China Uses Nepal suggest the Indian medias surprise at the possibility that South Asian countries could have relationships with nations other than India. It is also revelatory of the ignorance that Indian popular discourse about the subcontinent displays; anecdotal evidence would suggest the average Nepali knows more about contemporary Indian politics and society than vice-versa.

Such a narrow view of history leaves little room for the agency of other nations in the subcontinent, for history was not made overnight. Nepals newfound affinity to the north is not the result of one disputed road or a new map; rather, it is a decades-long process in which India has continuously erred and lost focus on issues around Nepal, while China has steadily gained it. While it has come at the expense of Indias political and economic ties with Nepal, there is little doubt even among the most nationalist of Nepalis that China will replace India in cultural, religious and social spheres. And yet, there is little evidence that Indian policy, or its media, which shapes the popular discourse, has attempted to understand the nuances that led the Nepali establishment to shy away from the corridors of Delhi. Instead, binary and outlandish views dominate, and because of Indias overwhelming global influence in shaping the South Asian narrative, the Nepali perspective is lost amid the cacophony of Indian news channels and the assumption of quasi-imperial notions on how the rest of the subcontinent should respond to India.

Levis study of Nepal through Tibetan and Chinese documents begins with descriptions by the seventh-century Chinese Buddhist pilgrim Xuanzang, also known as Hiuen Tsang, who wrote that, The Kingdom of Ni-po-lo has a circumference of about four thousand leagues. It is situated in the heart of the snowy mountains. The capital has a circuit of about twenty leagues... the inhabitants are naturally hard and ferocious; they do not consider good faith and justice as worth having and have absolutely no literary attainments; but they are gifted with skill and dexterity in the arts.

Buddhism was the locus of classical interactions between the three civilisations of Nepal, Tibet and China. A creation myth about Kathmandu reflects this: the bodhisattva Manjushri, who came from China, drained the primordial lake with his flaming sword and installed as king Dharmakara, who had accompanied him on his pilgrimage. Dharmakara organised Nepal with China as his model: sciences, knowledge, trades, culture, manners, commerce, all followed Chinese examples.

![Beverly M Lewis] - The Beverly Lewis Amish Heritage Cookbook](/uploads/posts/book/96304/thumbs/beverly-m-lewis-the-beverly-lewis-amish-heritage.jpg)