Introduction

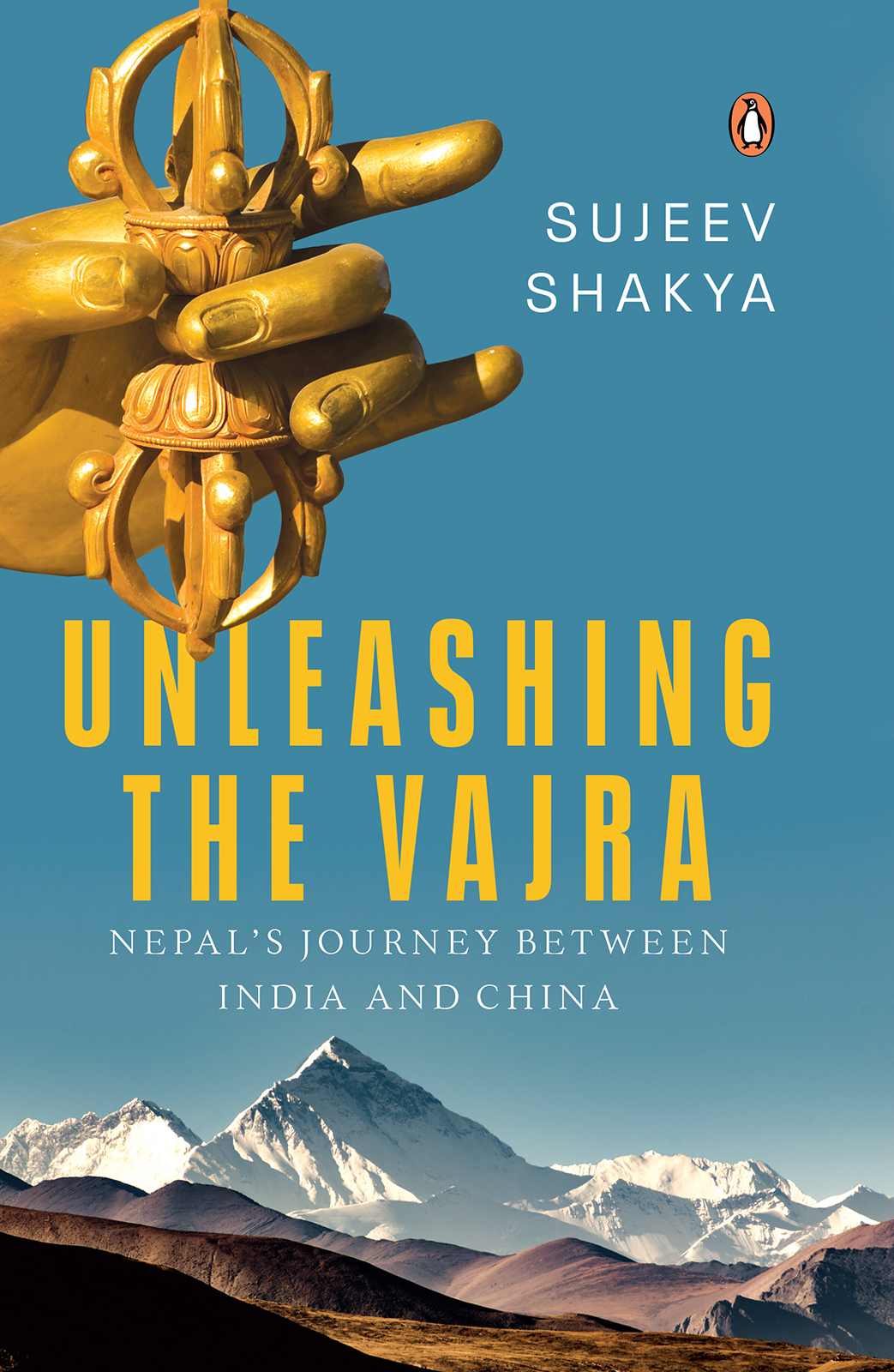

By 2040, it is projected that China will be the largest economy in the world, followed by India. The two put together will have nearly a third of the worlds population and GDP. This is similar to the glories of Asia in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, when India and China accounted for nearly 70 per cent of the global GDP. Nepal, till the seventeenth century, was known for being a trade link between China and India. The wealth accumulated by the Malla rulers of that time helped to create great architectural marvels with superb handcrafting skills, as well as trade with both nations. Now, there exists an opportunity for Nepal to unleash its potential and return to the time when it had the advantage of being in between two prospering neighbours. This book tries to understand the past in order to learn how to get the future rightNepal now has just two decades to relive its glorious past.

Writings on Nepal began with the British arriving in the subcontinent, and these were supplemented with accounts in the English language written by explorers. Together, this literature provides the background to Nepals history. Little is known about Nepal in the period before the Shah dynasty was established in 1776. The Newa language was then the lingua franca, and much of the history was transmitted orally. Archiving systems were poor and interest in history was limited. With the ban on the Newa language, the Shahs, and later the Ranas, decided what the narrative should be, and how it would be taught in schools. However, with the advent of multiparty democracy in 1990, the history recounted by the Shah kings began to be questioned and new narratives emerged.

After the fall of the Shah dynasty in 2008, with the extensive penetration of the Internet and the emergence of social media platforms, many new narratives came to the fore. Historians like 100-year-old Satya Mohan Joshi, who has seen major events in Nepal occur in his lifetime, started to openly talk about the past. His descriptions of the Newa craftsman Arniko who went to China and built temples and cities in Lhasa and Beijing spread far and wide and were not censored. The growing numbers of young and educated Nepalis were curious, and more stories started to emerge in Nepali magazines, books and online portals. In this book, I attempt to look at Nepali history from the year the Nepal era, popularly called the Nepal Sambat, began, in 879 CE . I try to piece together information from different sources, including the stories that we inherited from our ancestors.

Knowledge of the state of Nepals economy and society is understood from reports written by various development partners, including multilateral and bilateral agencies. These served a specific purpose and had a limited scope; very few explored history, culture and societal contexts. With the late development of the private sector and the concept of corporations, there was limited investment in research by business concerns as the core occupation remained trading, which was basically taking an arbitrage position on either taxes or the open border with India. The presence of only a few professional companies with foreign investment and the fact that Nepal was not a sought after investment destination were further hindrances in conducting studies on the impact of history, culture and consumer behaviour on business. This is in contrast to other countries, where it has become a major staple for consulting companies to produce reports. The use of the English language was limited; moreover, with the improvement of technology, the use of Nepali in typing and translation applications became more widespread, which restricted content availability in English. Many parts of this book have benefited from my effort of writing columns in Nepali; I had previously been inspired to write a book in Nepali titled Arthat Arthatantra (Its the Economy) in 2018. The interactions after the publication of this book provided multiple lenses for me to look at issues. I present them here.

Nepal has been widely perceived to be linked to India in many ways. It shares an open border and a fixed currency with India as well as a special treaty for transit and trade. Nepals rulers historically had links with India: the Lichhavis, Mallas, Shahs and Ranas. Even post-1990, most people at the helm of affairs in Nepal had educational, marital or other relationships with India. Tibet was Nepals other immediate neighbour, and it was only after 1960 that Nepal had to deal with China. The 1962 war between China and India led Nepal to consider a policy of allowing China and India to compete to provide aid to Nepal, but this was short-lived as both countries were fighting their own internal economic battles of population explosion and poverty. China continued to maintain that Nepal needed to deal with India for its internal security and trade issues. At that time, China just wanted to ensure that Nepal accepted the One China policy, and never allowed its soil to be used for uprisings or anything that posed a security challenge. It was only after the earthquake of April 2015 that mainland China started to take an interest in Nepal, and with the Indian blockade in September 2015, China got interested in Nepalit has not looked back since. After a very successful visit by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi in August 2013, followed by commitments at the SAARC summit in November 2014, and the assistance for relief and rebuilding after the earthquake, it was felt that there has been a recalibration in the NepalIndia relationship. This joy was short-lived and the relations that nosedived after the blockade are yet to return to normal. Even in PM Modis second term, there is hardly any indication of change. An Eminent Persons Group of six people, three each from India and Nepal, was formed to review the 1950 treaty, and their tenure expired in July 2019 without the report being accepted and implemented.

In the meantime, with the global churn of events in Europe, the US and the UK, China started to emerge as the new custodian of globalization, and the implementation of the One Belt One Road idea into a powerful programme under the acronym BRI (Belt and Road Initiative) accelerated. India did not join the BRI, but for Nepal this became a good opportunity to get out of being India-locked. New treaties were signed, and when Chinese President Xi Jinping visited Nepal in October 2019, he provided a new impetus to Nepalis by announcing that Nepal was now a strategic partner for China. A NepalChina Trans-Himalayan Multi-Dimensional Connectivity Network has been formed that will expedite land links with China, with the potential of railway links when the rail link to the southern parts of the Tibet Autonomous Region is built. A new chapter thus begins, and new opportunities open up for Nepal to define its relations with China. This book looks at some historical perspectives, and at cultural and practical on-the-ground issues to understand what Nepals journey has been, and what the future of Nepals journey in between China and India will be.