Photography Credits

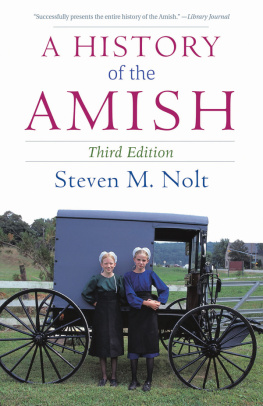

Covers: front and back, Jerry Irwin.

Jerry Irwin/Good Books, .

Copyright 2015 by Good Books, an imprint of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Good Books, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Good Books books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Good Books, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or .

Good Books is an imprint of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.goodbooks.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Cliff Snyder

Cover photos: front and back, Jerry Irwin

Print ISBN: 978-1-68099-065-2

Printed in the United States of America

In memory of

Abner F. Beiler (1917-2002)

who encouraged me to write the first edition of this book .

Contents

Acknowledgments

The themes of community and mutual aid are important in Amish history, and they have been critical to the process of writing and revising this book, as well. I received generous assistance and advice from numerous people. Special recognition goes to staff members of the Mennonite Historical Library of Goshen (Ind.) College, Archives of Mennonite Church USA, Goshen, Indiana; the Young Center for Anabaptist and Pietist Studies at Elizabethtown (Pa.) College; and the Heritage Historical Library, Aylmer, Ontario. Several Amish people in Indiana, Ohio, Ontario, and Pennsylvania read portions of the manuscript and offered suggestions and corrections. Individuals who supplied helpful information and critiques include Donald B. Kraybill, Thomas J. Meyers, Joe Springer, and Karen M. Johnson-Weiner. Steve Scott (1948-2011) deserves special mention for his insights, assistance, information, and friendship. I marvel at the confidence that Merle and Phyllis Good showed for a novice authors first book so many years ago, and I appreciate their interest in keeping the book updated and current.

For some reason it is customary to thank family members last, even though their contributions are most important. To Rachelwho has lived with Amish historical work for more than two decades nowand Lydia, and Esther, thanks for all your love.

Steven M. Nolt

Summer, 2015

A Reformation Heritage

We have been united to stand fast in the Lord.

Anabaptist leaders, 1527

A peculiar people in a land of grand expectations

For many Americans, the early 1960s seemed an era of buoyant optimism and impressive progress. Poverty rates were falling, life expectancy increasing, and modern medicine promised to end a host of dread diseases. A decade and a half of economic growth had boosted national and personal incomes to new heights and with it remarkable new consumer goods, from air conditioning to transistor radios. Weather satellites, jet airplanes, and other technological wonders gave people confidence that President John Kennedy was right when he vowed that humans would walk on the moon before the decade ended. Undergirding national prosperity was an expanding system of education and technical know-how, and the security that came from residing within the boundaries of a superpower whose global influence and military muscle supported an American way of life. Cold war tensions could put people on edge, but in the years before a deepening war in Vietnam, the assassination of Martin Luther King, or the cynicism of Watergate, the spirit of the times was one of grand expectation.

Amish families going home from church, Conewango Valley, New York. While the Old Order Amish are hardly isolated from modern society, they remain decidedly out-of-step with twenty-first century North American culture.

Near the crossroads community of Winesburg, in eastern Holmes County, Ohio, thirty-one-year-old Elizabeth Miller was not so sure. That year, Miller, an Old Order Amish farm wife and mother, penned several essays on church history and contemporary life. Apparently well-read and familiar with current events, Miller was nonplussed by many of the developments that others took to be progress. She had heard the puzzled questions often enough: Dont [you] care for the use of electricity and the pleasure of owning an automobile?

Surely Christ would not have led a homeless poor life as he did if it wasnt necessary for a follower of Christ to live a humble life as well, Miller reasoned, but in a society celebrating abundance it was difficult to explain why her family did not seek anything more than what is needed to live.

In some ways, Millers reflections on life in the 1960s expressed noticeably American themes. She condemned godless communism, for example, and gave money to the Red Cross and to fund a cure for polio. But her brand of patriotism differed from those who believe in fighting for their country with guns and bombs. She knew that the pacifist Amish are looked upon with scorn because they refuse to take up arms. She had attended the court hearings of Amish men sent to prison by military draft boards. Rather than seeing better days ahead, Miller wondered aloud whether her people could persevere in an environment where those in high places who administer the laws considered the Amish ignorant, illiterate, and unlettered.

A half century later, Millers community of faith has not only persisted in the midst of hypermodern society, but is a growing, vibrant group. As a plain and peculiar people, in Millers self-description, the Amish attract the attention of tourists and mass marketers who see the Amish as everything from examples of nostalgic conservatism to icons of postmodern environmentalism. For their part, the Amish insist they are not exactly any of these things. They are not timeless figures frozen in the past, nor the poster-children of political activists. Taken on their own terms, the Old Order Amish are a community that takes seriously the task of personal discipleship and collective witness to a particular Christian way of life that values humility, simplicity, and obedience. From their 1693 beginnings in Switzerland and the south Rhine Valley, to their immigration to North America and settlement in thirty U.S. states and the province of Ontario, the Amish have charted a distinctive history. At times, like Elizabeth Millers musing on current events, that story has been recognizably North American, yet it has also been markedly different from the dominant narrative of individual achievement and scientific progress that has shaped modern life.

One of the striking features of Elizabeth Millers writing was the ease with which she invoked the past. Her reflections on the present instinctively and repeatedly turned to stories from Amish history and accounts from old church martyr books. That Miller situated her peoples contemporary life in a long tradition of dissenting and suffering forebears is no surprise. The Amish are one of several spiritual heirs of the Protestant Reformations Anabaptist movement, and the source of Millers faith had roots deep in sixteenth-century Europe.

Turbulent times

In the early 1500s, an array of political and economic woes troubled Western Europe. For more than fifty years, a population explosion had seemed to outstrip the continents ability to feed itself. The Spanish conquistadors, who brought news of exotic new worlds across the sea, also brought shiploads of silver, plundered from the Americas. This destabilized European economies, producing inflation of prices and rents that drove land-owning peasants into poverty. In towns and cities, a growing class of wealthy merchants and craftspeople challenged the authority of hereditary nobles, while university scholars and disgruntled students voiced sharp criticism of public corruption.

![Beverly M Lewis] - The Beverly Lewis Amish Heritage Cookbook](/uploads/posts/book/96304/thumbs/beverly-m-lewis-the-beverly-lewis-amish-heritage.jpg)