Contents

Guide

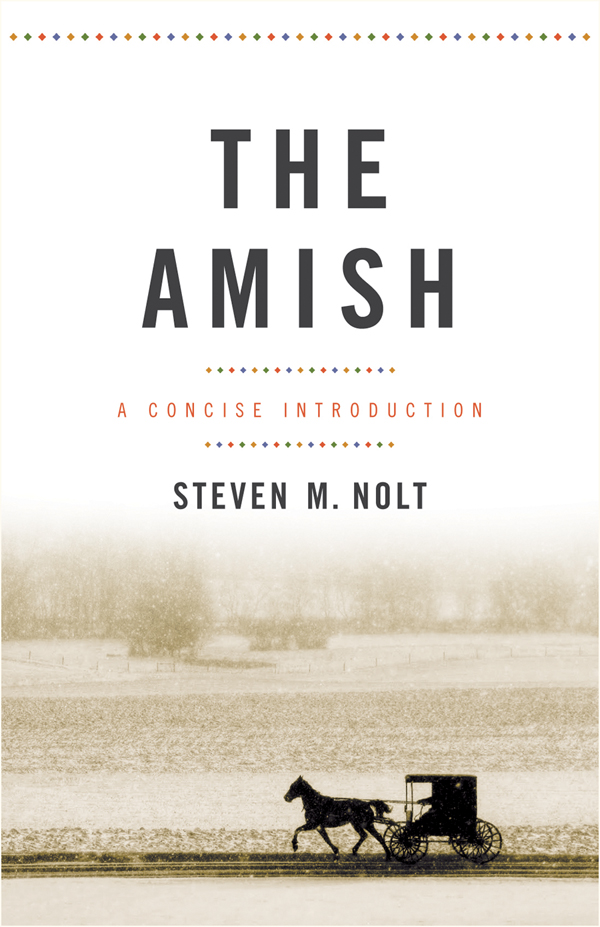

T HE A MISH

Y OUNG C ENTER B OOKS IN A NABAPTIST AND P IETIST S TUDIES

Donald B. Kraybill, Series Editor

THE AMISH

A Concise Introduction

Steven M. Nolt

J OHNS H OPKINS U NIVERSITY P RESS Baltimore

2016 Johns Hopkins University Press

All rights reserved. Published 2016

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1

Johns Hopkins University Press

2715 North Charles Street

Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363

www.press.jhu.edu

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Nolt, Steven M., 1968 author.

The Amish : a concise introduction / Steven M. Nolt.

pages cm. (Young Center books in Anabaptist and Pietist studies)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4214-1956-5 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 1-4214-1956-4 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4214-1957-2 (electronic) ISBN 1-4214-1957-2 (electronic)

1. AmishUnited StatesSocial life and customs. 2. AmishHistory. I. Title.

E184.M45.N65 2016

289.7'3dc23 2015028198

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

Special discounts are available for bulk purchases of this book. For more information, please contact Special Sales at 410 -- 6936 or specialsales@press.jhu.edu.

Johns Hopkins University Press uses environmentally friendly book materials, including recycled text paper that is composed of at least 30 percent post-consumer waste, whenever possible.

C ONTENTS

T HE A MISH

CHAPTER ONE

Meet the Amish

In 2013 an Amish father placed a notice in an Amish newspaper for a meeting of parents and teachers involved with Amish schools. Information about the gathering, to be held in Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania, ended with this reminder: If you are planning to attend and are using a GPS, you must use the correct spelling [for Punxsutawney].

The Amish use global positioning systems?

For many Americans, the image of the Amish as reclusive, dark-clad, horse-and-buggy-driving folks conjures notions of the nineteenth century and hardly comports with twenty-first-century satellite technology. In fact, most observers would either be perplexed by the notice or decide that it reveals some secret hypocrisy among a people who present a publicly plain life but behind the scenes are actually no different from the rest of us.

The truth is something else, as we will see, but the Punxsutawney school meeting lays bare distinctive aspects of Amish life in the modern world. None of the Amish reading the announcement has a drivers license. All of them rely on horse-drawn transportation for local errands. But for longer trips, most Amish families turn to non-Amish neighbors, hiring them to act as informal taxis. And many of those drivers rely on GPS, which the Amish recognize and understand.

That sort of give and takerefusing to own a car but hiring outside drivers and being aware of what those drivers want and expectreveals the dynamic Amish relationship with the wider world that well explore in this book. The Amish are a separate people, to be sure, but they are not as socially or technologically isolated as we often imagine. Instead, they interact with the wider world by bargaining with modernity. The Amish participate in modern life on their own terms. They might use batteries, for example, but not electricity from the public grid. While such choices may seem confusing from an outside perspective, this sort of flexible negotiating with the forces of modern life has allowed them to flourish.

Yet the Amish give-and-take extends only so far. The Punxsutawney meeting brought together Amish parents and teachers from across western Pennsylvania to discuss the day-to-day operations of Amish schools. Across the country some two thousand one- and two-room Amish schools exist in silent testimony to the refusal of parents to bow to the demands and promises of modern modes of education. Amish schools educate children only through the eighth grade, use a curriculum from the early 1900s, and employ teachers who themselves have had only eight years of schooling. During the 1950s and 1960s hundreds of Amish parents went to prison rather than send their offspring to consolidated public schools or to high schools of any kind. Their refusal to budge on this issue ultimately landed them before the U.S. Supreme Court, which in the case Wisconsin v. Yoder (1972) affirmed the Amish dissent from mass education and contributed to the jurisprudence of American religious liberty and minority rights.

An Amish woman loads her grocery purchases into a cargo van driven by a non-Amish neighbor who brought her to town. Credit: Joel Fath / Mennonite Historical Library

Combining a stubborn commitment to old-fashioned education with knowledge of GPS and the flexibility to hire drivers who use such systems, the meeting in Punxsutawney embodies aspects of Amish life that intrigue and perplex the rest of us.

Amish Myths

Popular images of the Amish sometimes resolve the puzzling aspects of Amish life with simplistic half-truths or outright misconceptions. These myths stem, understandably, from the potentially confusing diversity of Amish customs, as well as from the fact that the multi-million-dollar Amish-themed tourism industry (dominated by non-Amish players) sometimes offers up highly romanticized images of Amish life. And some of the misinformation derives from intentionally skewed presentations of Amish society that appear in reality television or Amish-themed fiction geared toward public entertainment.

Myths about the Amish include:

- The Amish are shut off from meaningful interaction with the wider world. They live in isolated colonies and shun all outsiders.

- The Amish are Luddites who live without technology and reject all modern conveniences. If you see an Amish contractor using a cell phone or an Amish teenager with in-line skates, they are acting on the sly and would be severely punished if Amish leaders caught them.

- Amish dont pay taxes or use modern medicine. They rely on mafia-style gangs to maintain order and they have very high rates of genetic abnormalities due to inbreeding.

- All Amish are farmers. They grow or hand-make nearly everything they use and rarely shop in stores.

- At age sixteen Amish children are sent out into the world to explore life in big cities before deciding if they want to come back home.

- Amish people have few choices in life. Bishops within the Amish church make all the decisions and women, especially, simply do as they are told.

- The Amish may live a bit differently than the rest of us, but they share the same basic cultural assumptions that the rest of us do and they represent the best of traditional American values.

- As relics from another age, the Amish are slowly but surely dying out.

Amish Reality: Diversity and Commonality

In the chapters that follow we unpack these and other misconceptions about Amish life, but for now well look at the last onethe idea that the Amish are a dying breed. In fact, the Amish population is growing rapidly, doubling about every eighteen to twenty years. Today more than 300,000 Amish peopleadults and childrenlive in the United States and eastern Canada. The largest Amish

![Beverly M Lewis] - The Beverly Lewis Amish Heritage Cookbook](/uploads/posts/book/96304/thumbs/beverly-m-lewis-the-beverly-lewis-amish-heritage.jpg)