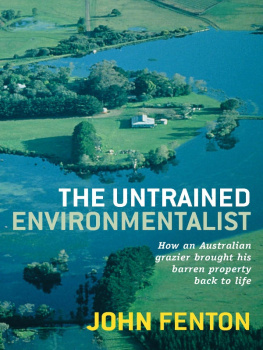

THE UNTRAINED

ENVIRONMENTALIST

How an Australian grazier brought his

barren property back to life

JOHN FENTON

First published in 2010

Copyright John Fenton 2010

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The Australian Copyright Act 1968 (the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218

Email: info@allenandunwin.com

Web: www.allenandunwin.com

Cataloguing-in-Publication details are available

from the National Library of Australia

www.librariesaustralia.nla.gov.au

ISBN 978 1 74237 019 4

Internal design by Phil Campbell

Map by Ian Faulkner

Set in 12/16 pt Janson Text LT Std by Bookhouse, Sydney

Printed and bound in Australia by Griffin Press

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper in this book is FSC certified.

FSC promotes environmentally responsible,

socially beneficial and economically viable

management of the worlds forests.

For my wife of 50 years, Cicely, and our very close family:

Amanda (and Charles), David (and Cath), Patrick (and Bronnie)

and John, plus our grandchildren, who have brought so much

joy to our livesClive, Anna, Lucy, Will, Harriet, Jock,

Georgia and Tanner

CONTENTS

Graeme Gunn

M.G. Cook

Jim Murphy

Murray Gunn

By Graeme Gunn

The father did not leave a forest for the boy, so the boy sowed his own seed and grew his own forest, and as the forest grew, the boy grew until he became a man a good man.

We were sitting on the terrace at Lanark one evening as the twilight sun hit the eucalypt plantation on the far side of Lake Cicely, when successive flocks of ibis crossed the sky heading south. We counted 6000 birds by our reckoningit was an armada, an awesome and remarkable sight. One had to assume that the waters of Lanark were a beacon for that night crossing.

John Fenton and I had grown up in Hamilton, the centre of a productive wool-growing area in the Western District of Victoria. We had known each other but did not establish a friendship until 1954 when we were in our early twenties; both keen to leave our mark on the world but without any apparent skills. At that time I was impressed by his self-effacing eccentricities and his principled and romantic approach to finding a worthwhile position for his own life. In answer to my questions about where he had been and what he was currently working on, he described his time away at boarding school in Geelong, his next educational adventure at Longerenong Agricultural College in central Victoria, and his removal from there with others for a minor drinking misdemeanour. He then told me of his most recent job, as a jackaroo on a significant grazing property in central Victoria. When asked what his tasks were as a jackaroo, he replied, Picking up sticks. I thought this both very funny and engagingly self-deprecating. We became solid friends and over the following 50 years have assisted each other and our extended families, intervened in each others lives and generally had a lot to talk about while extending each others knowledge.

I well remember in those early days in Hamilton how high and sometimes nave our aspirations were, and in retrospect, what little personal substance we had to realise them. During this early period while we were both still in Hamilton, I had bought a burnt-out MG car to hopefully restore to its proper state of glory. We spent nights grinding, scraping and sanding metal frames and panels, interspersed with the application of self-generated philosophical graffiti to the walls of the shed with fingers dipped in gelatinous grease.

The resurrection of the car succumbed to other pressures. I traded the carburetors I had bought to fund my move to Melbourne to study architecture and John focused on the embryonic farming property he had inherited near Branxholme, a small hamlet some 25 kilometres from Hamilton.

John had inherited the property from his father, who died when John was young, and his move into farming was consequently different from that of most of his peers. They had grown up on established grazing properties working under parental regimes and conservative farming practices that gave little credence to land care, conservation and the benefits of integrated environments.

John started with a windswept grassland property generally devoid of trees and endowed with some rudimentary structures: two small cottages, a small shearing shed and a small antiquated grain and tool shed. A row of semi-mature pines lined the northern road frontage of the property but these, together with a small stand of sugar gums near the sheds, were not a great defence against the prevailing cold southwesterlies that ripped across the paddocks to chill the spine and rock the cottage.

There were some advantages in taking over such an undeveloped rural canvas. John faced a lot of challenges but these could be met without the trappings of established conservative practices and hierarchal authority. The dreams of creating a farming enterprise that balanced good farming practice with conservation and environmental programs to enhance the rural landscape were part of a distant horizon, but they were realisable, personal dreams, possible of being achieved without interference. This rather lonely pursuit, while not easy, developed in John strong independent characteristics that were assisted and balanced by his lovely, suitably rational soul mate, Cicely.

I have spent many hours at Lanark over the years on my return trips to Hamilton and saw each of the innovative transformations which were applied to this once bare portion of rural land. It was always a delight to see a new water body or a new plantation, initially as habitat and shelter belt and later as part of the farms productivity program extending the landscape and realising the dream.

During the 1950s and early 1960s, sheep farming in the Western District reached a peak, aided by the Korean War and developing international markets. Then, following a major drought in 1967 and the advancing competitive quality of synthetic fibres, the wool industry suffered a dramatic decline. The damage caused by the drought and the slowness of landholders to adopt more appropriate techniques to land management had been significant. The Fentons early reintroduction of water bodies surrounding their farmhouse helped to generate a new approach to droughtproofing, fire protection, stock sustenance; all integrated with an evolving natural landscape.

Their farm developed in response to a new sensitivity and a perception of land use that will be necessary for the future wellbeing of the land, of farming practices and also for those involved in the process.

Next page