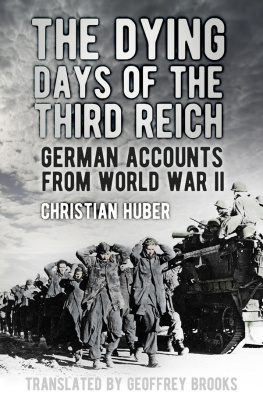

In 1945, as the army retreated, the German people were surrendered to the enemy with no means of defence. A wave of suicides rolled across the country as thousands chose deathfor themselves and their childrenrather than face the defeat of the Third Reich and what they feared might follow.

Drawing on eyewitness accounts, historian Florian Huber tells of the largest mass suicide in German history and its suppression by the survivorsa fascinating insight into the feelings of ordinary people caught in the tide of history who saw no other way out.

We reached another town towards morning. Demmin.

At the end of the dead-straight avenue, a massive church tower was silhouetted against the dim light of dawn. The rows of sycamores, receding into the distance, led the eye to the tip of the spire, which pointed, needle-like, into the soft pink skya tissue-paper cut-out scored with a razor blade, at once slender and powerful, filigree and solid. It was the first time that Irene Brker had seen anything to break the monotony of the landscape. All she had to do now was to make straight for it.

Irene Brker was a twenty-three-year-old woman who in late April 1945 was fleeing with her familyor what was left of itfrom the north-eastern city of Stettin. Her husband, Werner-Walter, had been missing since the previous autumn, and she had been separated from her parents, father-in-law and sister-in-law during an air raid the day before as they passed through the town of Anklam. Her parents carriage had been left behind with a broken wheel, while she was shunted out of town in her car, caught up in the dense flow of vehicles, people and horses. When she looked for her family later, she couldnt find them. Only little Holger, her two-year-old son, was still with her. She was careful not to let him stray from her side.

The two of them were not, however, entirely alone; in Lcknitz, a few miles west of Stettin, they had been joined by an elderly doctor and his wife. Like many women faced with hardship after a previously well-ordered life, Irene Brker had developed remarkable coping skillsnot only the ability to suppress all but her most vital emotions, but also the art of finding allies in strangers. Dr P., as Irene Brker calls the doctor in her memoirs, was to be her greatest support in the days to come. She knew that difficulties lay ahead; she had even provided for a time when she might no longer want to live. On a string around her neck, Irene Brker carried a small watertight pouch.

Towards morning, then, they arrived in Demmin. For Irene Brker it was just another name on the escape route; the town surrounding the red-brick church tower that dominated the landscape for miles around held neither memories nor meaning for her. The end of her march lay much further west, beyond the reach of the Russian soldiers.

The horrors of the winter trekfrosty nights and snowstorms on icy roadswere a thing of the past. The second half of April was marked by beautiful spring weather; the countryside was burgeoning. A haze of young green covered the trees and fields; the days were warm, the nights mild. Apart from the occasional shower, there was no rain. But like so many others, Irene Brker and the doctor and his wife had made only halting progress during the night. By the time they reached the eastern outskirts of Demmin that morning, they were worn out.

We got bogged on a sandy track and had to abandon some luggage to get going again. Many, many valuables had already been left by the roadside and in the fields. We stopped on the outskirts of Demmin, at a big house next to the cemetery. The occupants had fled town that evening. Too exhausted to go any further, we treated ourselves to a nights rest.

After many sleepless nights, broken only by the occasional chilly nap by the roadside when the trek came to a halt, Irene Brker had lost all sense of time and was longing for a rest. The stopover in Demmin wasnt supposed to be more than a quick breather. But the town was a bottleneck. There were three rivers to be crossed on the road west.

A few hundred yards from the house where Irene Brker slept, a unit of Wehrmacht soldiers had taken up quarters at a former Prussian cavalry barracks. Among them was Gustav Adolf Skibbe, a fifty-three-year-old from the West Prussian city of Elbing. Skibbe had entered the war late. If the Volkssturmthe old men and Hitler Youth boys called up to serve as a national militiawere the countrys last reserves, Skibbe was among the second-to-last. A few months earlier, hed been hoping to survive the war at home with his family, but since general mobilisation in January 1943, the civilian population had been sifted with an ever finer sieve until he, too, was caught in its mesh. Skibbe was conscripted in December 1944. Scarcely two months later, his native Elbing was lost in a fierce battle, and he spent the weeks that followed far from the action, mainly around Berlin, nearly five hundred kilometres to the south-west. Then, on 14 March, he came to Demmin. It was four weeks since hed last seen his family. It was a trying part of the war for him; there was a lot of waiting and toiling and standing around on draughty railway stations. His bones ached; he felt his age. Wretched night, sore feet, he writes in the slim notebook he used as a war journal. In Oranienburg, thank God, I was given insoles.

In his journal, Skibbe kept a brief record of the places where he was billeted, his health andon rare occasionshis emotions. He wasted hardly a word on the war itself, and less still on politics.

In Demmin, Skibbes unit was billeted in the former Uhlan Barracks on Jarmener Strasse. He was kept busy theremainly, his journal suggests, servicing and repairing machinerybut he noticed the mood of nervous apprehension that had taken hold of residents and refugees alike. He noticed, too, their growing distrust of the troops who were to defend them.

Everything at sixes + sevens. Got hold of sawdust mattresses. 3 men, Mller, Schink and I, sleep in backroom. V. primitive. People v. subdued, almost desperate because of overcrowding in town.

Days passed without much of note. There was a lot of work to be done. Skibbe concentrated on his machines and, in between times, made the most of the lovely spring weather. On the east side of town, women and schoolchildren dug miles of steep-sided anti-tank ditches and drove wooden stakes into the ground to make tank traps, while the never-ending flow of refugees surged between them into town in dense clutches. The Red Army, which had begun its advance on Western Pomerania, drove them along like water before the bow of a ship.

Demmin-born Marie Dabs, daughter of a sea captain and wife of the furrier and gentlemens outfitter Walter Dabs, was familiar with the refugees. Wave after wave of them had passed through town since February, some staying with relatives, others in rooms or dormitories allocated by the billeting office. Most of them carried on westwards, but they were soon replaced by the next lot. Since her husband had been called up, Marie Dabs had been living alone with her children, Nanni, nineteen, and Otto, fifteen, in the flat behind their shop on Luisenstrasse. The billeting office had sent her an elderly refugee woman from Memel, who complained all the time and hogged the kitchen. She was forever frying, Marie Dabs remembered later, especially in the evenings. They had let her have Ottos bedroom, which was soon the worse for wear. When the woman moved on west with her daughter, two young sisters from another refugee family moved in, this time taking over Nannis newly decorated room.

Next page