THE BRUNEVAL RAID

Operation Biting 1942

KEN FORD

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Prior to World War II, both Britain and Germany had independently discovered that radio waves could be used to detect aircraft. Thus began the race to develop and deploy radar before the other side could put the process to effective use. For the first year or so of the conflict, each side thought that it was leading the race.

Britain was confident that it was well ahead in the radar war and in a sense it was. Although German radar was of a high quality and as advanced as British equipment, its application and administration was not as effective. The Nazi military still regarded their role as being offensive rather than defensive and tried to employ the new technology to that end. Britain, in contrast, was more inclined to use the new equipment to protect itself from the horrors of aerial bombardment and had effectively integrated radar into its inter-service defence network. It had set up systems to exploit the information gained from radar. In this respect it was well ahead of Germany.

Britain had begun its research into what was eventually to become known as radar in 1935. At the time its scientists were studying the possibility of destroying enemy aircraft by means of death rays. Such an idea might seem fanciful now, but in the 1930s the advances made in science appeared to show that anything was possible. A common fear was that enemy bombers could suddenly appear overhead to wreak havoc on civilian populations and every method that could lead to their detection and destruction was given serious thought.

A leading member of the committee at that time looking into air defence was a scientist from the Radio Research Station, Robert Watson-Watt. He concluded that whilst it was impossible to destroy enemy aircraft through radio waves, it should be possible to detect them by bouncing radio energy back from the aircrafts metal body. He was led to this conclusion by investigations made by one of his colleagues, Arnold Wilkins, who was intrigued by observations made by Post Office radio engineers that aircraft flying though a high-frequency radio beam caused the beam to become distorted. An experiment was set up to prove this point to RAF observers in February 1935 and the results were so impressive that funds were made available to develop the idea. The process was termed Radio Detection Finding (RDF) and the whole procedure was considered so revolutionary and important that it was given a Top Secret level of security.

The early development of RDF, which eventually became known as RA dio D etection And R anging RADAR (later to lose its capital letters and become radar), was carried out by Watson-Watts team at the Telecommunications Research Establishment (TRE) at Bawdsey Manor in Suffolk. Within a year a working system had been developed. It used transmitters radiating a pulsed sequence of radio waves in the 20MHz30MHz band, which were reflected by aircraft flying into the beam. The reflections would then be detected on receivers located adjacent to the transmitters. The system demonstrated itself capable of detecting aircraft up to a distance of 130km. This proven arrangement was then integrated into Britains air defences and, by the time that war was declared, a string of these radar stations, known as Chain Home, were located along the east and south coast of England and the east coast of Scotland.

The Chain Home stations did valuable work identifying German attacks during the Battle of Britain in 1940. The system would pick up incoming enemy aircraft whilst they were well out to sea and its controllers would vector RAF fighters to intercept them. The arrangement worked well but its effectiveness and importance was not immediately realized by the Luftwaffe, which allowed the RAF to have the upper hand during a most crucial period.

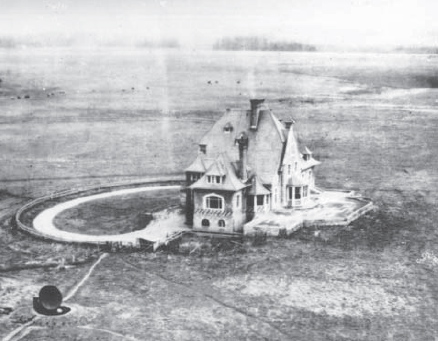

The buildings of Le Presbytre at Bruneval. The farm complex was used as a barracks for the Luftwaffe signallers and operators manning the radar sites. After the raid the area was fortified with the addition of Tobruk machine-gun posts and concrete gun emplacements. (Ken Ford)

Home are the conquering heroes. A group of delighted paratroopers from C Company arrive alongside the Prinz Albert in the Solent after their return from the raid on Bruneval. This successful airborne operation against Hitlers occupied Europe became the first battle honour awarded to the Parachute Regiment. (IWM H17358)

Further development work in Britain saw improvements in radar ground control interception of enemy aircraft using rotating antennae and higher frequencies. Other smaller airborne systems were engineered to allow aircraft-to-aircraft interception and the detection of submarines by aircraft whilst the boats were on the surface. Perhaps the most important development in the history of radar was the invention of the cavity magnetron by John Randall and Harry Boot at Birmingham University in 1940. This small device allowed for the generation of microwave frequencies much more efficiently, and enabled Britain to develop radar in the 3GHz band. These ultra-high frequencies enabled the detection of smaller objects using much more compact antennae and consequentially freed up the deployment of radar apparatus from the cumbersome equipment of the previous years. The cavity magnetron was the single most important invention in the history of radar. This remarkable piece of apparatus was given as a free gift to the USA, along with several other inventions, as part of an inducement to enter the war on the side of the British.

In the meantime, Britain was slow to appreciate that Germany and many other countries were also making progress in the field of radio waves. Each had scientists working on equipment that operated at shorter and shorter wavelengths, and each was very protective of the knowledge gained by its researchers. There was little interchange between countries on developments, all therefore progressed in something of a vacuum, so Britain entered the war with many of its important scientific advisers believing that the country was far ahead of any of its rivals and certainly well ahead of Germany.

Radar was not the only field in which other nations were making remarkable progress and often led the way. Germany was at the forefront in tank, aircraft and weapons design and was innovative in the way these new machines were being deployed. Air power was fundamental to the success of Germanys Blitzkrieg tactics and its experimentation in the use of airborne troops gave the country a powerful edge over other belligerent nations. Nor was the use of paratroops confined to the Nazi regime, for Soviet Russia had for years been experimenting with airborne forces. On a trip to Russia in 1936, General Wavell had watched a demonstration of Stalins air power. He witnessed a whole battalion of 1,200 men, led by a general and complete with 150 machine-guns and eighteen light field guns, successfully drop on its target. If I had not witnessed the descents, he later wrote, I could not have believed such an operation possible. Britain lagged well behind these new developments and at the start of the war had no airborne forces of its own.