THE BLOCKING OF ZEEBRUGGE

Operation Z.O. 1918

STEPHEN PRINCE

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Launched on St Georges Day, 23 April 1918, the British raids on the Belgian ports of Zeebrugge and Ostend are among the most famous and controversial episodes of World War I. Sir Winston Churchill later wrote that they may well rank as the finest feat of arms in the Great War, and certainly as an episode unsurpassed in the history of the Royal Navy. The debate had begun even before the ships involved had returned to England and has continued ever since. All authors have acknowledged the great gallantry of the raiders, with a total of 11 Victoria Crosses being awarded across the three individual actions, but there has been no consensus on whether the operations led to any real military advantage for the Allies.

The raids were relatively simple in concept. Imperial German submarines, destroyers and torpedo boats were operating from the inland Belgian port of Bruges and by 1918 they were sinking around a quarter of all ships being lost off Britain. The distance of Bruges inland acted as an effective protection from Allied bombardment. The German vessels based there accessed the sea via a network of canals which connected to open water at the coastal ports of Zeebrugge and Ostend. The Royal Navy (RN) planned to seal these canals by sinking blockships at their entrances, thus trapping the German ships. At Zeebrugge, where the canal entrance was protected by a large projecting sea wall or Mole, it was also intended to place a converted cruiser alongside the Mole. This cruiser would then disembark a mixed force of Royal Marine (RM) and Royal Navy storming parties. The attack was designed to destroy German defences, or at least distract and occupy them, so that the blockships had a better chance of reaching their objective. The crews of the blockships were to be rescued by a supporting force of motor launches and destroyers, with monitors, cruisers and aircraft providing bombardment and cover for the assault force.

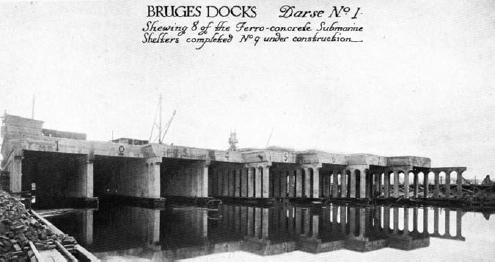

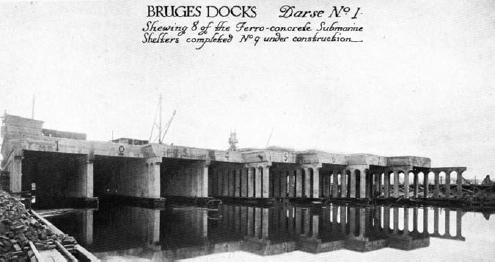

The German U-Boat shelters at Bruges in a post-war Allied photograph. While Bruges distance from the coast provided effective defence against naval bombardment, air attack became an increasing problem. The small size of bombs and the limited accuracy with which they could be targeted meant that the shelters were an effective defence. These shelters were the forerunners of the much larger and more extended series of U-Boat pens built along Europes western coast during World War II. [NHB]

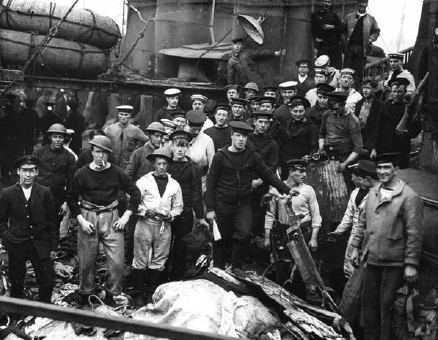

Sailors of the Royal Naval Division (RND) manning defences at Antwerp in 1914. The RND was an ad hoc formation, formed by Winston Churchill, using sailors for whom there was no immediate employment afloat. Initially the formation resembled a large scale landing party, as shown by the dated arms and equipment of these men. These formations had frequently been successful throughout the Royal Navys history but World War I was a far more challenging conflict than those encountered in the decades before. The men had little infantry training and no supporting arms. They were intended to be used for landings, raids and port defence, but were rushed to help defend Antwerp in October. As it became clear the defence was not viable, the division retreated, losing over 2,400 men to capture or internment in Holland. [NHB]

The German defences were formidable in number, sophistication and integration having been steadily developed during over three years of German occupation. At Ostend, the more limited of the canal exits, the defences completely frustrated both the initial raid and the attempted follow-up attack on 10 May. At Zeebrugge the raiders succeeded in putting the cruiser HMS Vindictive alongside the Mole to attack and distract the defenders and two of the three blockships were sunk in the canal entrance. Britain immediately claimed a significant success in blocking the canal and frustrating German sailings for weeks, with continuing disruption thereafter. By contrast Germany claimed that the British raiders had been defeated and, in the words of Admiral Scheer, commander of Germanys High Seas Fleet, that connection between the harbour at Zeebrugge and the shipyard at Bruges was never interrupted even for a day. The significance of the Zeebrugge raid, as for many prominent raids, has always been as much about its psychological impact and utility for propaganda, as about the direct physical effects achieved.

Reconciling these incredibly diverse views of the operation, with the literature often falling into overwhelmingly supportive or critical camps, is one of the main difficulties of assessing the raid. However, it is possible to achieve a balanced account. This involves examining the operation from both the Allied and the German side, the latter of which is often neglected but for which there are now also some excellent English language sources. It also involves placing the raid in the wider context of the campaign for access to the eastern end of the English Channel, a campaign that was crucial to the survival of the Entente powers (originally the British Empire, France and Russia) and one which was fought throughout the four years of World War I.

Churchill, Sir Winston, The World Crisis 19161918, Part II, Thornton Butterworth (London, 1927) p.371.

Grove, Eric, The Royal Navy Since 1815 A New Short History, Palgrave (Basingstoke, 2005) p.139.

Scheer, Reinhard, Germanys High Sea Fleet in the World War, Cassell & Company (London, 1920) p.339.

ORIGINS

Britains concern about potentially hostile control of the north-west coast of Europe, particularly what is now the coast of Belgium and Holland, has endured for centuries. Naval forces operating from this coast have had the opportunity to block or disrupt Britains vital maritime trade, exploiting the short ranges from this area to achieve rapid effects, often before superior Royal Navy forces could be deployed to intercept them. This concern has been one of the drivers for frequent British military involvements in the Low Countries, though ironically these involvements have then led to further concern about control of the coast because of the resulting army supply line. Frances occupation of Belgium in 1793 was a casus belli for Britains series of wars with France until 1815. Britain was then instrumental in ensuring that the 1837 Treaty of London established a Five Power guarantee of both Belgiums independence and its neutrality. When Britain declared war in August 1914 Germanys infringement of Belgian neutrality was the immediate cause. Not only did this attack challenge Britains view of international law and behaviour, but its particular location meant it was also seen as a significant threat to Britains survival.

This concern was also an accurate reflection of Germanys ambitions, with control of Belgium and later Holland, including their ports, remaining a German war aim throughout the conflict. Belgiums largest port, Antwerp, was captured in October 1914, despite an attempt by Winston Churchill, then First Lord of the Admiralty, to intervene with the Royal Naval Division (RND), at that point an