T he he names and identifying details of some people in this book have been changed. While this is a work of nonfiction and the author has selected what to include, it is based on his own perspective, notes, and recollection of events. The author thanks the real-life members of the Harvard Square homeless community portrayed here for accepting him during the times they shared together. The author especially thanks Neal, Dane, George, and Chubby John for sitting down with him and sharing their stories when he was writing this book. These interviews were conducted during the summer of 2012, three years after the author spent time on the streets of Harvard Square. The authors royalties from the sale of this book are being contributed to charities to help people in need.

L et us be dissatisfied until the tragic walls that separate the outer city of wealth and comfort and the inner city of poverty and despair shall be crushed by the battering rams of the forces of justice. Let us be dissatisfied until those that live on the outskirts of hope are brought into the metropolis of daily security. Let us be dissatisfied until slums are cast into the junk heaps of history, and every family is living in a sanitary home.

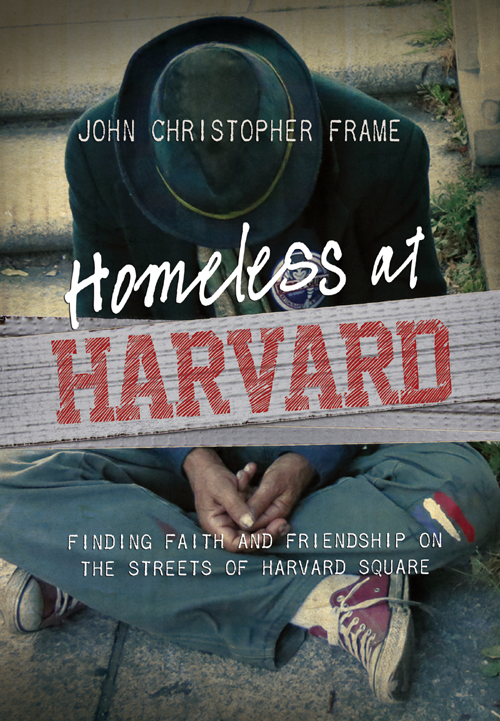

I stood and gawked. Bundled in warm blankets and sleeping bags, people were asleep and nestled under the outdoor alcove of the Harvard Coop bookstore, across the street and about a hundred feet away from the gates of Harvard Yard. They were motionless, like bodies ready to be picked up by an undertaker; lonely, like campers expelled from an expedition.

I had decided to get off the subway to look around a place that was as foreign to me as the homeless individuals now sleeping in my presence. I was sightseeing that October night while in Boston for a conference. However, I wasnt expecting to see anything, or rather anyone, like this in Harvard Square, the business district around Harvard University.

Leaving Harvard Square that night, I didnt know if Id ever walk by that bookstore again. Soon, though, Id meet some of the people who had slept there. And less than two years later, I was sleeping there myself.

That night was similar to a night a year earlier in London, England, when I met a homeless man who was sitting on a sidewalk next to a King Rooster fast-food chicken restaurant. I had walked by him twice, and then wrestled with a voice within me telling me to turn around, go back, and offer him one of the two bananas I had just purchased at the corner market. I gave in to it.

As I approached the man, he reached out his hand and said in a British accent, Sir, could you do me a favor? Heres five pounds. Will you go in there and buy me a dinner? As he dropped the coins in my palm, I noticed that his hand was cold and chapped, cracked and seeping blood.

This was my first experience of meeting a homeless person, and he was giving me money, entrusting me with perhaps all the money he had. I asked him what he would like. Chicken dinner was all he said, in a broken, almost stuttering voice. When I returned with his meal, we talked for a while on the sidewalk, his two-liter bottle of white cider beside him. We shared the same first name, and I learned that John had a debilitating muscular disease, a teenage son, and a mother he loved but had not seen in a long time.

John sat on the sidewalk and his cane rested against the restaurant. Passersby gave him coins, which he graciously accepted, and after a few minutes, a man and a woman joined us. John openly shared with us about his troubles. He cried as we prayed together, as if his brokenness or maybe it was hopelessness needed to be heard. Though I left John that night to return to the comforts of my privileges, our brief encounter stayed with me.

I grew up in a red brick house with a large, narrow lawn that my friends and I imagined as a major league baseball field. All summer long we played baseball with a yellow plastic bat and ball, trying to hit the ball over the fence into the church parking lot behind the parsonage where I lived. I announced every hit and strikeout as if I were broadcasting it like the radio voice of the Detroit Tigers, Ernie Harwell, and we dreamed of being as good as the players pictured on our bubblegum cards. Then wed ride our bikes and play cops and robbers with my collection of cap guns and metal handcuffs, which looked as genuine as the ones in the police shows on TV. Because my dad was the pastor of a small church and my mom was a part-time teacher, my sister and I didnt grow up in a rich family. We had everything we needed, though, and most things any boy would hope to have, like a Nintendo, a cocker spaniel named Dixie who was my best friend, a newspaper route, and a fishing pole and a tackle box. Each night, Id help set the table that my family gathered around for a homemade meal, and I was in our church several times each week. Besides seeing a few people around our city who looked down and out, I really knew nothing about homelessness.

In my late twenties, while pursuing a masters degree at Anderson University School of Theology, I felt inspired to get to know those who were living on the streets. My friends at Anderson, the author of a book I had read, and spring break trips to Atlanta to serve with a homeless ministry there helped me better understand how Christians should be concerned about the poor.

The day after I moved into my dorm on Harvards campus in 2008 to begin a theology degree, I met a homeless man, George, sitting near his bedding, which was strewn out in front of a bank in Harvard Square. George helped me learn more about homelessness, as did some of his friends, such as Chubby John. I began spending time with them and also volunteering at the student-run Harvard Square Homeless Shelter, partly to fulfill a requirement for a Poverty Law class I was enrolled in. I began learning more about homelessness and about the relationships that help homeless people survive on the streets.

In a leadership class I took at Harvard, my professor taught us about translating life experiences into new actions that serve a greater purpose. I thought some more about how what I was learning about homelessness could be translated into something that could benefit others. For a long time, Id wanted to write a book that could somehow make a difference, and I thought that by sharing my experiences with homeless people more broadly, I could help others think about building relationships with people on the streets. It seems that those who do not know homeless people are often unaware of their circumstances and struggles. In general, many of us are unaware of how the homeless view themselves and their difficulties. Were unaware of how similar we are to individuals who are panhandling on the sidewalk. A glimpse of the experiences of those who live on the streets could help change that, I thought.

The thought of temporarily staying on the streets with the homeless had begun to grow in my mind since my second spring-break trip to Atlanta. So while taking my final class at Harvard during the summer of 2009, I took the plunge and slept outside among the homeless community for ten weeks. I didnt do it as a way to emulate Christ or to show that living on the streets is more righteous than living in a home. And I didnt do it in an effort to save people on the streets from their homelessness. Rather, I hoped it would give me a chance to learn about homelessness as an insider, which would better enable me to write about the stories and struggles of those who were really homeless; and I could share what it was like to spend a summer on the streets.