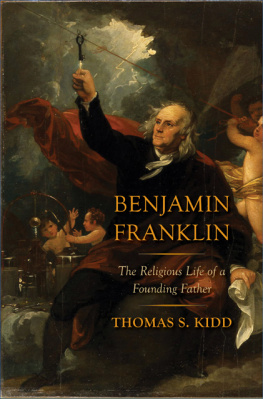

BENJAMIN FRANKLIN

Published with assistance from the Annie Burr Lewis Fund.

Published with assistance from the foundation established in memory of Amasa Stone Mather of the Class of 1907, Yale College.

Copyright 2017 by Thomas S. Kidd.

All rights reserved.

This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational, business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail (U.K. office).

Set in Janson type by IDS Infotech Ltd., Chandigarh India.

Printed in the United States of America.

ISBN 978-0-300-21749-0 (hardcover : alk. paper)

Library of Congress Control Number: 2016956723

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992 (Permanence of Paper).

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Introduction

1787. THE CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION , Philadelphia. Time dragged as delegates bickered about representation in Congress. Virginias James Madison insisted that states with more people (including slaves) should possess more power. The small states knew that under the Articles of ConfederationAmericas existing national governmentall states had equal authority, regardless of population. Why should the small states give that power up under a new Constitution? The convention might have failed at this point. If it had, the country would have continued to struggle under the inefficient (some said feckless) Articles government. Or the new American nation might have disintegrated.

At this critical moment, the octogenarian Benjamin Franklin took the floor. Calling for unity, he asked delegates to open sessions with prayer. As they were groping as it were in the dark to find political truth, he queried, how has it happened that we have not hitherto once thought of humbly applying to the Father of lights to illuminate our understandings? If they continued to ignore God, they would remain divided by our little, partial, local interests, our projects will be confounded, and we ourselves shall become a reproach and a by-word down to future ages. This man, who called himself a deist, now insisted that delegates should ask God for wisdom. This was strange: classic deists did not believe that God intervened in human affairs.

Even more strange, he was one of the few delegates who thought opening with prayer was a good idea. His motion was tabled. What kind of deist was this elderly man, dressed in his signature Quaker garb, calling on Americas greatest political minds to humble themselves before God?

Franklin, of Philadelphia. In our minds eye, the man seems ingenious, mischievous, and enigmatic. His journalistic, scientific, and political achievements are clear. But what of Ben Franklins faith? Was Franklin defined by his youthful embrace of deism? His longtime friendship with George Whitefield, the most influential evangelist of the eighteenth century? His work with Thomas Jefferson on the Declaration of Independence, and its invocations of the Creator and of nature and Natures God? Or his solitary insistence on prayer at the convention? When you add Franklins propensity for joking about serious matters, he becomes even more difficult to pin down. Regarding Franklins chameleon-like religion, John Adams remarked that the Catholics thought him almost a Catholic. The Church of England claimed him as one of them. The Presbyterians thought him half a Presbyterian, and the Friends believed him a wet Quaker. This biography illuminates Ben Franklins faith, even as it tells the story of his remarkable career in printing, science, and politics.

The key to understanding Franklins ambivalent religion is the contrast between the skepticism of his adult life and the indelible imprint of his childhood Calvinism. The intense faith of his parents acted as a tether, restraining Franklins skepticism. As a teenager, he abandoned his parents Puritan piety. But that same traditional faith kept him from getting too far away. He would stretch his moral and doctrinal tether to the breaking point by the end of his youthful sojourn in London. When he returned to Philadelphia in 1726, he resolved to conform more closely to his parents ethical code. He steered away from extreme deism. Could he craft a Christianity centered on virtue, rather than on traditional doctrine, and avoid alienating his parents at the same time? More importantly, could he convince the evangelical figures in his lifehis sister Jane Mecom and the revivalist George Whitefieldthat all was well with his soul? (He would have more success convincing his sister than Whitefield.) When he ran away from Boston as a teenager, he also ran away from the citys Calvinism. But many factorshis Puritan tether, the pressure of relationships with Christian friends and family, disappointments with his own integrity, repeated illnesses, and the growing weight of political responsibilityall kept him from going too deep into the dark woods of radical skepticism.

Franklin explored a number of religious opinions. Even at the end of his life he remained noncommittal about all but a few points of belief. This elusiveness has made Franklin susceptible to many religious interpretations. Some devout Christians, beginning with the celebrated nineteenth-century biographer Parson Mason Weems, have found ways to mold Franklin into a faithful believer. Weems opined that Franklins extraordinary benevolence and useful life were imbibed, even unconsciously, from the Gospel. There is something to this notion of Christianitys unconscious effect on Franklin. But Weems had to employ indirection because of Franklins repeated insistence that he doubted key points of Christian doctrine. Other Christian writers could not overlook those skeptical statements. The English Baptist minister John Foster wrote in 1818 that love of the useful was the cornerstone of Franklins thought, and that Franklin substantially rejected Christianity.

One of the most influential interpretations of Franklins religion appeared in Max Webers classic study The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1905). For Weber, Franklin was a nearperfect example of how Protestantism, drained of its doctrinal particularity, fostered modern capitalism. Franklins The Way to Wealth (1758), which distilled his best thoughts on frugality and industry, illustrated the spirit of capitalism in near classical purity, and simultaneously offers the advantage of being detached from all direct connection to religious belief, Weber wrote. Franklins maxims conveyed an ethically-oriented system for organizing ones business. For Weber, Franklins virtues were no longer a matter of just obeying God. Virtue was also useful and profitable. Franklin, admonished by his strict Calvinist father about diligence in ones calling, presented money-making and success as products of competence and proficiency in a vocation. Webers Franklin grew up in an intense Calvinist setting but redirected that

Many recent scholars have taken Franklin at his word by describing him as a deist. Others have called him everything from a stone-cold atheist to a man who believed in the active God of the Israelites, the prophets, and the apostles. Deism stands at the center of this interpretive continuum between atheism and Christian devotion. But other than indicating skepticism about traditional Christian doctrine, deism could mean many things in eighteenth-century Europe and America. The beliefs of different deists did not always sync up. Some said they believed in the Bible as originally written. Others doubted the Bibles reliability. Some believed that God remained involved with life on earth. Others saw God as a cosmic watchmaker, winding up the world and then letting it run on its own. Deism meant different things to Franklin over the course of his long career, too. He did not always explain those variant meanings. I am not opposed to calling Franklin a deistindeed, I do so in this bookbut deist does not quite capture the texture or trajectory of Franklins beliefs.

Next page