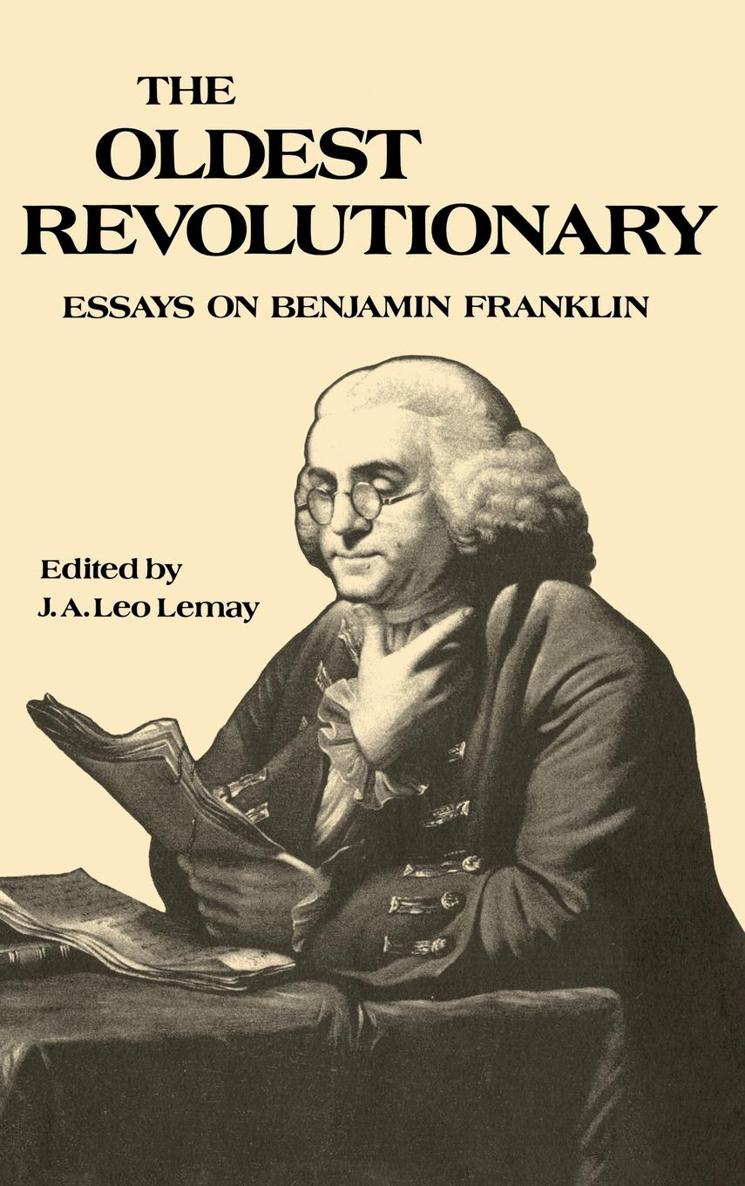

The Oldest Revolutionary

Essays on Benjamin FranklinPERCY G. ADAMS

BRUCE I. GRANGER

JOHN GRIFFITH

WILLIAM L. HEDGES

J. A. LEO LEMAY

CAMERON C. NICKELS

DAVID L. PARKER

LEWIS P. SIMPSON

P. M. ZALL

THE OLDEST REVOLUTIONARY

Essays on Benjamin Franklin

Edited by J. A. Leo Lemay

Copyright 1976 by The University of Pennsylvania Press, Inc.

Cover portrait of Franklin from painting by C. W. Peale, courtesy of the American Philosophical Society.

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 75-41618

ISBN: 0-8122-7707-4

In memory of

THEODORE HORNBERGER (1906-1975)

Our teacher and friend

Contents

Lewis P. Simpson

Bruce I. Granger

Percy G. Adams

P. M. Zall

David L. Parker

Cameron C. Nickels

J. A. Leo Lemay

John Griffith

William L. Hedges

Benjamin Franklin, the oldest Revolutionary, embodied the European ideas of America at the outbreak of the American Revolution. America meant possibility, especially the possibility for the common man to become uncommon. America was the promise of a new life, a better life, a dream for the future. America promised that a man might not only become free from pressing financial worryhe might also renew his spirit and recreate himself as a new man. America held out the prospect of new possibilities for mankind, for democracy, and for the individual.

Franklins fame as a scientist, his renown as a spokesman for democracy, his espousal of mankind, of the possibilities of life, and of Americaall tended to create an image of Franklin as the representative American.

He was and he wasnt. Leaving aside the unpleasant reality of the impossibility for the mass of common men to become uncommon (the impossibility for those with little extraordinary talent and little determinationthe men of no demonsto become famous), there is still Franklins own unsuitability for the role of the representative American. In addition to his extraordinary talents, unflagging energies, great pride, and even greater ambition, we must still confront the Franklin who was not only NOT a true believerhe was most assuredly a practical, hardheaded, commonsensical realist.

His unflinching realism did not result in pessimistic, paralyzing nihilism. Instead, he advocated a Pascal-like attitude toward life and human beings and oneself. He urged skeptics and pessimists to live as if life were enjoyable, as if fellow human beings were worth-while, and as if one respected and liked oneself. For only if one went through these motions could the possibility exist for life to be good. And if one continuously lived life as if it were good, then this might finally become the fact.

In Franklins day there was no widespread national malaise concerning America, and he was not writing primarily for skeptics and pessimists, or even for those, like himself, who had journeyed through a dark night of the soul. (When he fell extremely ill at twenty-one, he was not unhappy to die, and felt discouraged only when he began to recover and found that he would have the whole disagreeable prospect of life before himbut he made the most of it.) He wrote the Autobiography primarily for late-eighteenth-century adolescents and young adults of the Old World who were looking for standards, looking for ways to live, looking for places to live, looking for possible attitudes toward life, and looking for models. He wrote it with great art. And if we can escape our own preconceptions of Franklin as the representative American of our late-twentieth-century America, and imagine him speaking for the America of 1771, of 1784, and of 1788when he wrote the book and when America was possibilitythen we may not, perhaps, blame him quite so much for being the representative American of an America that we have created. Or if we read what Franklin actually wroteand are blinded neither by the 1775 or the 1975 image of America nor by Franklin as (what he never was) the representative Americanthen we may learn something of the truth, as well as the art, of his writings. The truth includes Franklin the idealist, refusing in his mid-sixties the British overtures of a sinecure in order to cast his lot with the New World. The oldest signer of the Declaration of Independence was a man who at sixty-nine risked his comfort, fortune, and life when his peers (and his son) were retiring with what money they could take out of the colonies to the safety of Englands leisure world.

The following essays deal with some of the writings and some of the activities of Franklin. Taken separately, they provide valuable insights into what Franklin was and wrote; taken together, they provide an overview of Franklins attitudes, purposes, and significances as a writer and thinker for his own time and for ours.

L. L.

Los Angeles, California

Lewis P. Simpson

I, Benjamin Franklin, of Philadelphia, printer, late Minister Plenipotentiary for the United States of America to the Court of France, and President of the State of Pennsylvania...

Although he had not followed the printing trade since 1748, when he had withdrawn from active participation in a printing and bookselling house to enter upon his various and widely influential public life as man of letters and statesman, Franklin recognized in his last will and testament in 1788 that the second part of his career was at one with the first. He confirmed the prophecy of his career made at the age of twenty-two, when the youthful Philadelphia printer, suffering from pleurisy, had somewhat prematurely composed his own epitaph.

The Body of

B Franklin Printer

(Like the Cover of an old Book

Its Contents torn out

And stript of its Lettering & Gilding)

Lies here, Food for Worms.

But the Work shall not be lost;

For it will, (as he believd) appear once more,

In a new and more elegant Edition

Revised and corrected

By the Author.

as Carl Van Doren calls it, Franklin exemplifies his ability to make homely apostrophe the ironic mask of sophisticated cultural observation. When the individual existence inevitably falls into disrepair, according to Franklins vision of things, it will be brought out in a new and more beautiful edition by a God who, like Franklin, is not only an author but a printer. He will both correct the errata of the first edition and make the new edition typographically elegant. In Franklins epitaph salvation by faith in the regenerating grace of God becomes faith in the grammatical and verbal skills and in the printing shop know-how of a Deity who is both Man of Letters and Master Printer.

This symbolic representation of the God of Reason is as appropriate to the Age of the Enlightenment as the more familiar symbolism depicting Him as the Great Clock Maker. In proclaiming his adherence to deism, Franklin implies his rejection of the order of existence under which he had been reared, that of the New England theocracy. He suggests an awareness of his affiliation with an order of mind and spirit which as yet existed only in tentative ways in colonial America: an order additional to the realms of Church and Statethe autonomous order of mind, the Republic of Letters, or a Third Realm, being made manifest as never before in Western civilization by the advancing technology of printing. Franklins epitaph signifies the historical engagement of his whole career with the articulation of, and the expansion and consolidation of, the Third Realm in America.