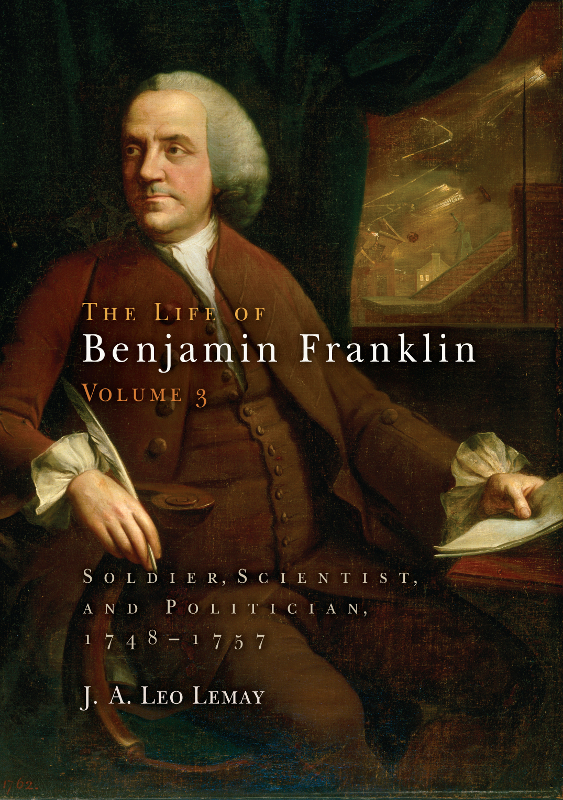

The Life of Benjamin Franklin VOLUME 3

The Life of Benjamin Franklin

VOLUME 3

Soldier, Scientist, and Politician 17481757

J. A. L EO L EMAY

PENN

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia

Copyright 2009 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 191044112

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lemay, J. A. Leo (Joseph A. Leo), 1935

The life of Benjamin Franklin / J. A. Leo Lamay.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Contents: v. 1. Journalist, 17061730v. 2. Printer and publisher, 17301747v. 3. Soldier, scientist, and politician, 17481757

ISBN 0-8122-3854-0 (v. 1 : acid-free paper).ISBN 0-8122-3855-9 (v. 2 : acid-free paper).ISBN 978-0-8122-4121-1 (v. 3 : acid-free paper)

1. Franklin, Benjamin, 17061790. 2. StatesmenUnited StatesBiography. 3. ScientistsUnited StatesBiography. 4. InventorsUnited StatesBiography. 5. PrintersUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

E302.6.F8L424 2005

973.392dc22

[B]

2004063130

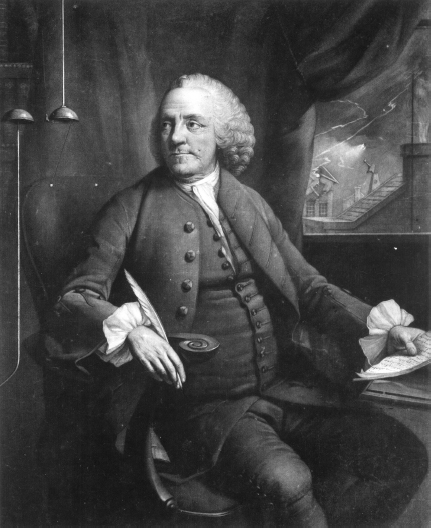

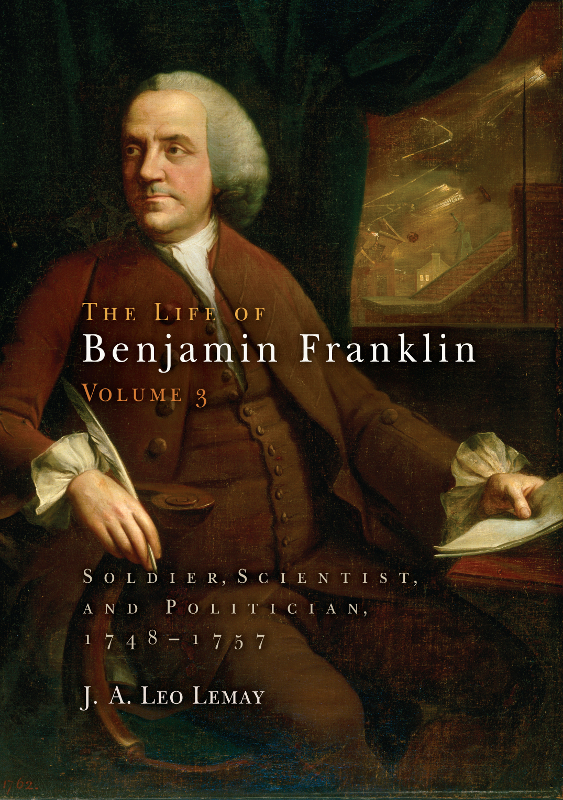

Frontispiece: Benjamin Franklin, mezzotint by Edward Fisher after Mason Chamberlain. Courtesy, National Portrait Gallery.

Endpapers: Map of Franklins Philadelphia with key places of interest indicated. Reprinted from The Papers of Benjamin Franklin, ed. Leonard W. Labaree et al. (New Haven, Conn.: Yale University Press, 1959), vol. 2, facing p. 456. Courtesy, Ellen R. Cohn.

The biography as a whole is dedicated to Ann C. Lemay, John C. Lemay, Kelly and Lee C. Lemay, and Kate C. Lemay

This volume is for Carla Mulford and David S. Shields, who were aided and abetted by A. Owen Aldridge, Robert D. Arner, Ralph Bauer, Pattie Cowell, Wayne Craven, Thomas J. Haslam, James Egan, Armin Paul Frank, Roy Goodman, James Green, Kevin J. Hayes, Bernard Herman, Susan Clair Imbarrato, Robert Micklus, Barbara B. Oberg, Daniel Royot, Gordon M. Sayre, Karen N. Schramm, John Seelye, Nanette G. Tamer, Frank Shuffelton, Susan M. Stabile, Leonard Tennenhouse, and Paul M. Zall.

Contents

Illustrations

Franklins Philadelphia endpapers

Benjamin Franklin, mezzotint by Benjamin Martin, after Mason Chamberlain frontispiece

FIGURES

MAPS

Preface

A T THE BEGINNING OF 1748, Franklin was known in Pennsylvania as clerk of the Pennsylvania Assembly and in the Middle Colonies as the printer and editor of Poor Richards Almanac and the Pennsylvania Gazette (the best colonial newspaper). By the middle of 1757, however, he had become famous in Pennsylvania as a public-spirited citizen and a soldier; well-known throughout America as a writer, politician, and the most important theorist of the American empire; and renowned in the western world as a natural philosopher. This volume tells the story of that transformation.

In late 1747, Britains war with Spain and France had been under way since 1741 and 1744, respectively. French and Spanish ships were raiding up and down the colonies Atlantic coast and even in the Delaware Bay. With an organized force of fewer than several hundred, enemy troops could have plundered the entire city of Philadelphia. The Pennsylvania Assembly, dominated by the Quaker Party, refused to provide defense. Franklin proposed a volunteer militia, aroused the public, and raised more than ten thousand volunteer troops in Pennsylvania. He organized a successful lottery that raised funds to buy cannon and build fortifications to defend Philadelphia. When peace was proclaimed in August 1748, he was the most popular person in Pennsylvania.

During the same period, Franklin devoted whatever time he could spare to electricity. News concerning its inexplicable marvels had appeared in popular magazines in 1745. In 1746 European electrical experimenters created the Leyden jar, an early capacitor. It could build up and store an electric charge that would be released when the inside and outside of the bottle were connected. Its effects were astonishing. Two hundred Swiss guards, with hands joined, would all be shocked and jump instantaneously upon receiving the electric charge. No one understood how the Leyden jar worked. Franklin offered the first good explanation, based partly on the atomic theories of the Greeks. He theorized that electricity was not created; rather, it separated existing elements into positive and negative charges. He also suggested that atmospheric electricity existed; hypothesized that lightning was an electrical discharge; and experimented to test the hypothesis. During the first several years of his electric experiments, English electricians ridiculed him. Then, following Franklins directions, the French tested and proved correct his theories that clouds could contain electric charges and that lightning was electrical in nature. He quickly became the best-known living natural philosopher, and the Royal Society of London awarded him its Copley medal in 1753the most prestigious existing scientific award, comparable to todays Nobel Prize.

Franklin was also interested in weather, and like all almanac makers, he wondered if one could go beyond the comments on the seasons and prediction of eclipses. Almost by accident, he tracked the progress of hurricanes and found that although the winds in the great storms blew from the northwest, the storms actually moved up from the southeast. Having established the southeast-to-northwest direction in which the storms moved, he hypothesized why and where they started and why they traveled in a northwest direction. Taking into account the effects of trade winds, the Appalachian Mountains, and the behavior of hot and cold air, his hypotheses were simple, crude, and brilliant. So too were his ruminations on tornadoes, whirlwinds, and waterspouts. They were the best explanations, thought Captain James Cook, that existed. Franklin was Americas first scientific weatherman.

In 1749 Franklin started the Academy and College of Philadelphia (now the University of Pennsylvania). Franklins basic idea for the academy was to educate youths who were approximately thirteen to eighteen in ways that would prepare them either for further study or for a career in business. Franklin projected a radically different education as an alternative to the apprenticeship system and to the existing elite academic schools. The latter taught youths Latin and a little Greek, which were the requirements for entrance into the colleges of the dayHarvard, Yale, and William and Marywhere one further studied Latin and Greek. The apprenticeship system taught a youth a specific trade, which he then practiced for the remainder of his life. Franklins Academy of Philadelphia would be primarily an English, mathematical, and agricultural school, with an emphasis on the study of modern languages (French, Spanish, and German) rather than Latin and Greek. But the major financial contributors to the academy wanted the traditional curriculum; Latin and Greek at first supplemented and then gradually superseded Franklins proposed curriculum.

Next page