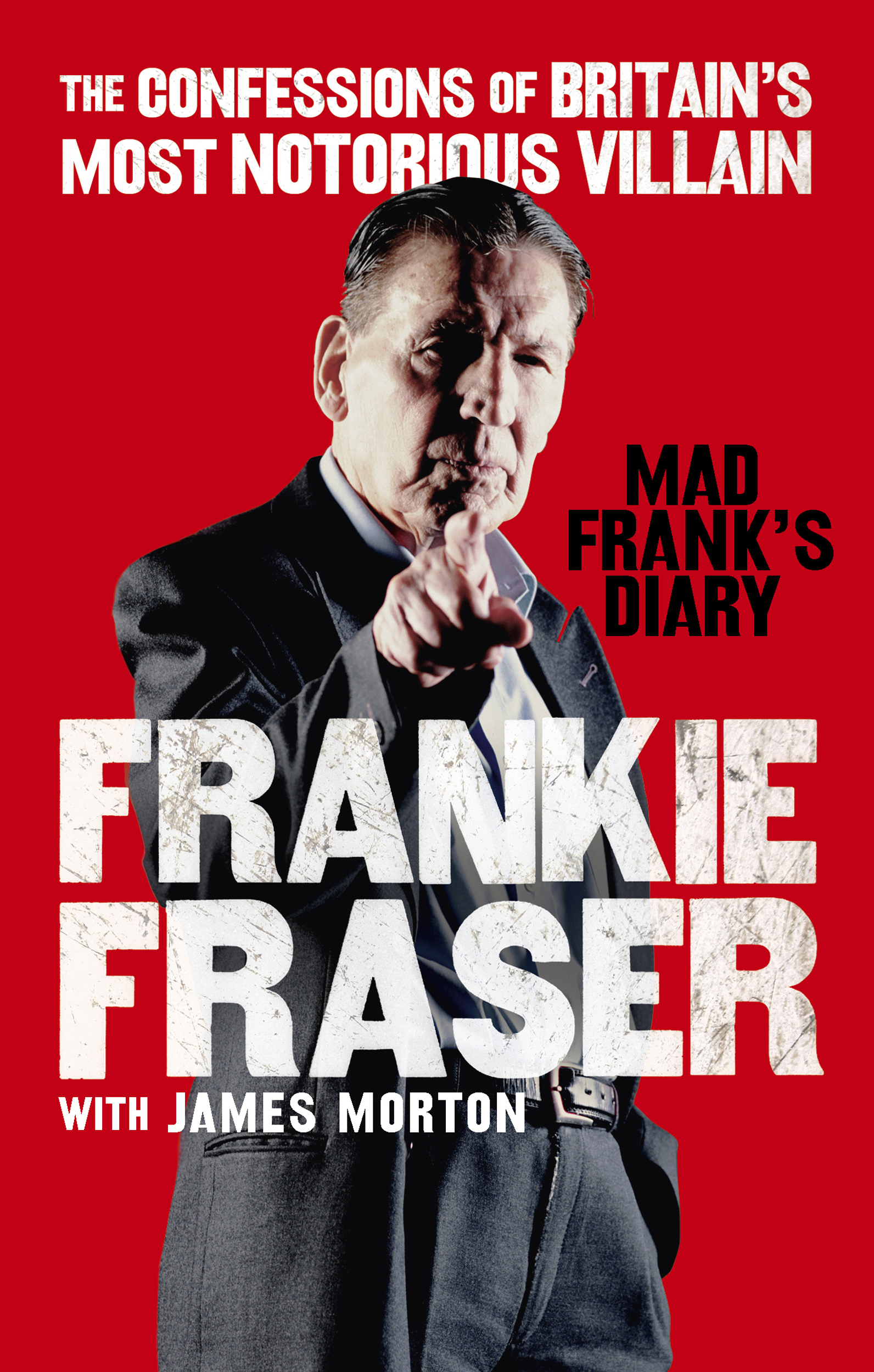

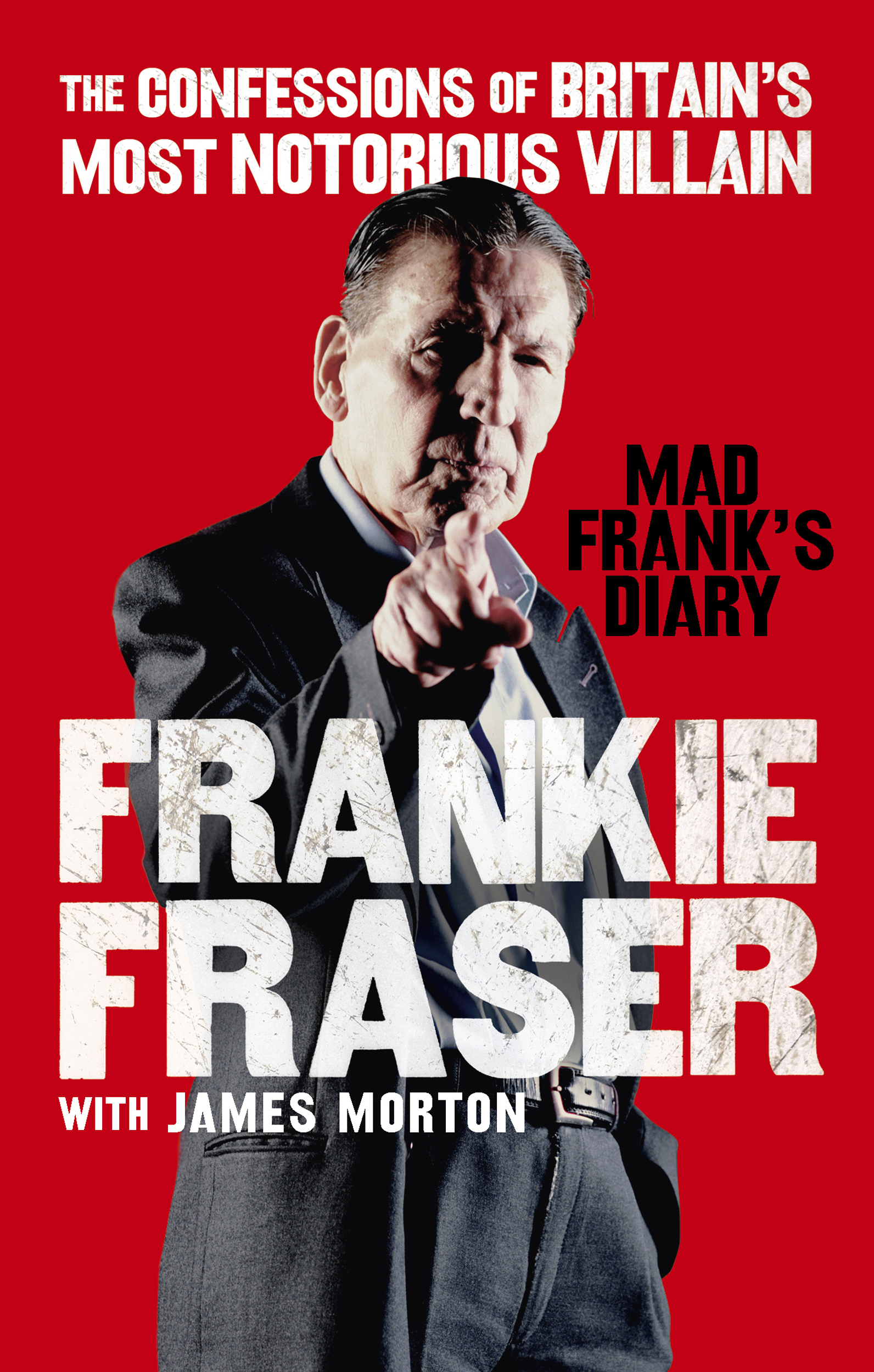

MAD FRANKS DIARY

The confessions of Britains most notorious villain

FRANKIE FRASER WITH JAMES MORTON

CONTENTS

About the Author

Previously a solicitor for twenty-five years, James Morton then worked as editor of Law Journal and Criminal Lawyer. He is now a full-time writer and author of the bestselling Gangland series.

An extraordinary insight into another world Hes so shamelessly upfront that youll soon find yourself hanging on his every word.

Mirror

As entertaining as his last two works you would be mad to miss it.

Publishing News

Introduction by James Morton

The first time I met Frank Fraser was in the spring of 1970. He was immaculate in his prison clothes a brown battledress and a blue and white striped shirt. He was serving 15 years: five years for an affray in March 1966 at Mr Smiths Club in Catford and ten for his part in the so-called Richardson Torture Case. In the affray, he had been acquitted of the murder of Dicky Hart, a Kray friend/associate/even relation, depending on who you ask. Now he was in the dock in Ryde town hall on the Isle of Wight, charged with incitement to murder, grievous bodily harm and a string of lesser offences following the Parkhurst Prison Riot in 1969, which the prosecution, quite rightly, claimed that he had led. His sister Eva, for whom I had acted in an offshoot of the Torture case, had asked me to represent him.

What was his background? Frank (that was the name on his birth certificate, Francis came later) Davidson Fraser was born in the Waterloo area of London on 13 December 1923. He was the fifth child of a part native-American father and an Irish-Norwegian mother. It is possible his father had a served a sentence for manslaughter in Canada, but neither parent had convictions for dishonesty. The first three children had no criminal convictions, and only he and his sister Eva, to whom he was devoted, made a life out of crime. She became a member of the celebrated Forty Thieves, a long-running gang of female shoplifters who would pillage West End and other inner-city stores, stuffing clothes, bedding, glassware and silver goods down their specially made bloomers.

In the 1920s, much of crime in Londons West End was run by the half-Italian Sabini brothers from Clerkenwell, led by Ottavio, better known as Darby. Also known as the Raddies, they had fought a running battle with the so-called Brummagen Boys, who included a number of men from the Elephant and Castle, over the control of bookmakers on the free course at racetracks such as Epsom and Brighton as well as trotting tracks at Hendon and Hurst Park. Fraser worked for the Sabinis as a bucket boy taking round the sponges used to wipe off the bookmakers chalked-up odds as they changed in pre-race betting.

When Italy declared war on Britain in the 1940s, the Sabinis were interned and the face of London crime changed. Now the Jewish gang leader Jack Spot, who spuriously claimed to have fought off Sir Oswald Mosleys Blackshirts during the so-called Battle of Cable Street, was very much a leader in the East End, while Frasers mentor Billy Hill from Holborn was active in the black market. After meeting him in Chelmsford prison, it was to Hill that Fraser hitched his star. For a time, Hill and Spot teamed up running London crime in a benevolent dictatorship, but after the war the Italians, now led by Pasquale Papa who had boxed as Bert Marsh, wanted the return of control of the racecourses. Hill and Spot fell out, culminating in a bad slashing of Spot for which Fraser went to prison. It was during Frasers sentence for the wounding that the Krays emerged as the East End gang leaders, while in South London the Richardson brothers Charlie and Eddie ruled.

Back on the Isle of Wight, after the committal proceedings I set about preparing his defence and interviewing his fellow prisoners who had witnessed the riot or were able to talk about the conditions in the prison which had led to it. On the first occasion I saw half a dozen inmates, and at the end of the afternoon I saw Fraser. He was livid. I was surprised, I had thought that an afternoon out of what amounted to solitary confinement to talk to his friends would have pleased him. It had not. In fact, it was like Nol Coward in the first version of The Italian Job, for whom the prison film show has to wait until he is seated. Frank had to be seen immediately, so confirming his status as head of the prison hierarchy. Anything else was an insult. We agreed that from now on he would be the first. It was the only time we ever exchanged harsh words. He was acquitted of the incitement to murder but convicted of GBH and given another five years to make a total of 20. With the loss of his remission following attacks on warders and prison governors he served every day.

The next time I saw him was in the autumn of 1992. I had just published Gangland, a history of London crime over the previous century, and had had a little trouble with a family who had not been over keen on what I had written about them. That had been sorted out and now I had a message on my answering machine. Would I telephone a Mr Francis Fraser? It had to be about Gangland. The last thing I wanted was Mad Frank on my back, but there was no point in trying to hide. Is that the Mr Fraser? I asked.

Yes, Ive got your book. I didnt buy it. I had it nicked. Theres some things wrong in it.

Well, I said in my most conciliatory manner, Ill correct them if theres a second edition.

No, he said, I want a meet. Im writing my book and I want you to do it for me.

We met the next day. He was late and had his arm in a sling. He apologised effusively saying he had fallen off a ladder and had had to go to hospital. I said he should have cancelled the meeting but he disagreed: No, I said I was coming and so Ive come. And after that, over the next 15 or so years, I found this was the case with him. If he said he would do something he would do it, whether it was breaking a mans nose or keeping an appointment. He was never less than well turned out, his shoes shined, his dyed hair immaculate. If he said hed be somewhere at a set time, there he was, five minutes or so early talking to one of the many people who admired this dapper little man. And if I was, say, five minutes late he would greet me with, Beginning to think we were meeting tomorrow, James.

No one had wanted me to write the book with him; certainly not my agent, who was at least partially mollified when Mad Frank received a major review in the Sunday Times. Frank had a fantastic memory. It was easy to do the back-up research. If he spoke of a murder which had nothing to do with him, say, in February 1942 in Wandsworth, he would have the date right within a month either way. On the other hand, he could be evasive if he did not wish to answer a question. Cant remember, James. Its no good, it just wont come to me.

As anyone who has done a book signing will tell you, unless you are very, very famous, it can make for a very lonely hour or two. I once went to a northern town for a signing and it was not until five minutes before my allotted hour was up that anyone came near me. Hope sprang. It was going to be worthwhile after all. But all the man said was, Do you know Frank Fraser? When I said I did, he muttered, Give him my regards, and sloped off.

So when Mad Frank

Next page

![Frankie Gaw - First Generation : Recipes from My Taiwanese-American Home [A Cookbook]](/uploads/posts/book/409729/thumbs/frankie-gaw-first-generation-recipes-from-my.jpg)