Alexander Frater

TALES FROM

THE TORRID ZONE

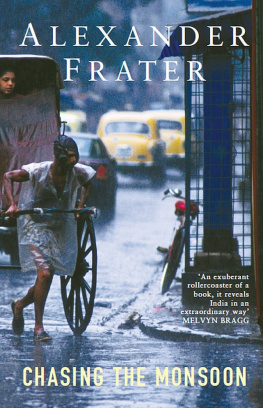

Alexander Frater was chief travel correspondent for The Observer and has written for numerous other publications, including The New Yorker and The New York Times. He lives in London but travels frequently to the tropics.

Also by Alexander Frater

Chasing the Monsoon:

A Modern Pilgrimage Through India

Beyond the Blue Horizon

FIRST VINTAGE DEPARTURES EDITION, FEBRUARY 2008

Copyright 2004 by Alexander Frater

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. Originally published in Great Britain by Picador, an imprint of Pan Macmillan Ltd., London, in 2004, and subsequently in hardcover in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, in 2007.

Vintage is a registered trademark and Vintage Departures and colophon are trademarks of Random House, Inc.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the Knopf edition as follows: Frater, Alexander, [date]. Tales from the torrid zone : travels in the deep tropics / Alexander Frater.

1st American ed. p. cm.

1. Frater, Alexander, 1937TravelTropics. 2. Voyages and travels.

3. TropicsDescription and travel. I. Title.

G910.F73 2007 910.913dc22 2006049552

eISBN: 978-0-307-79525-0

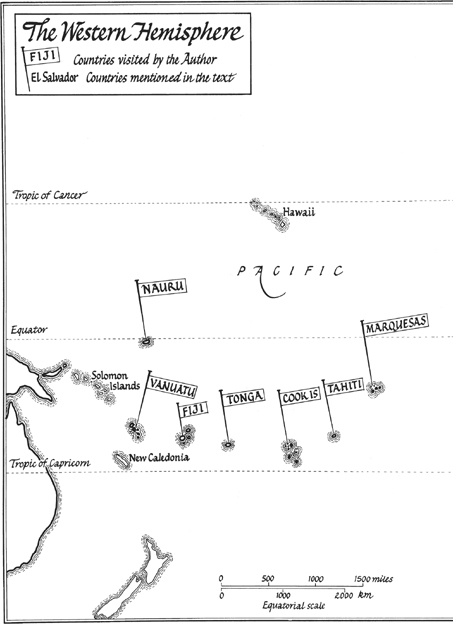

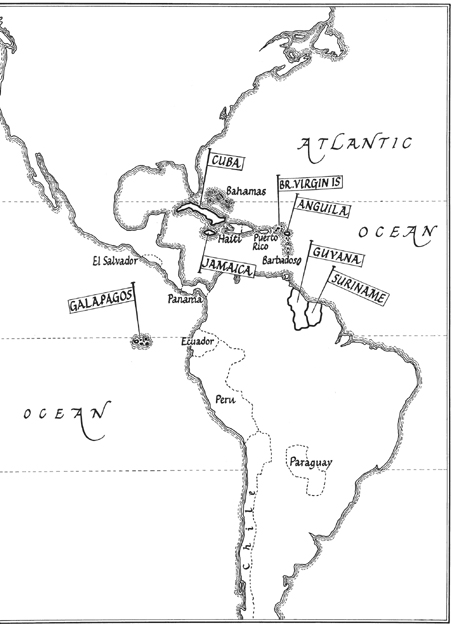

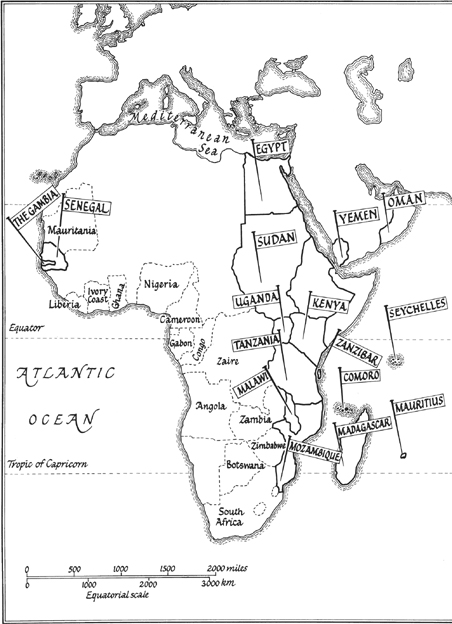

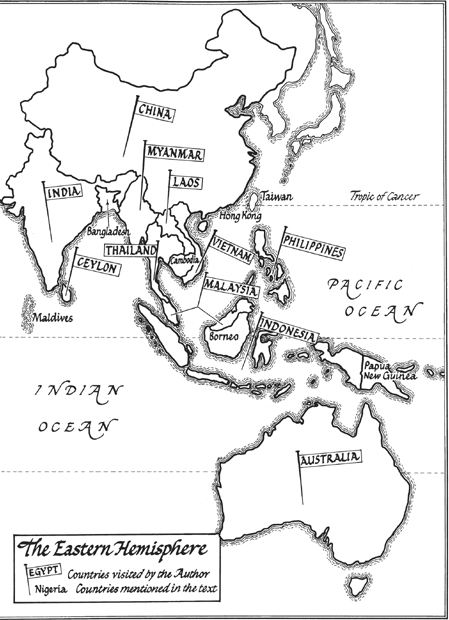

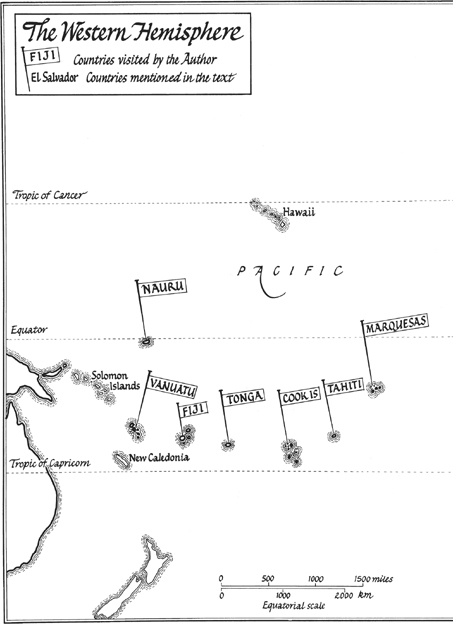

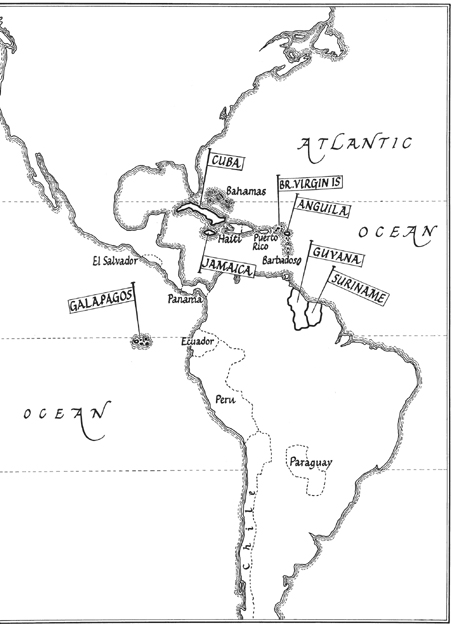

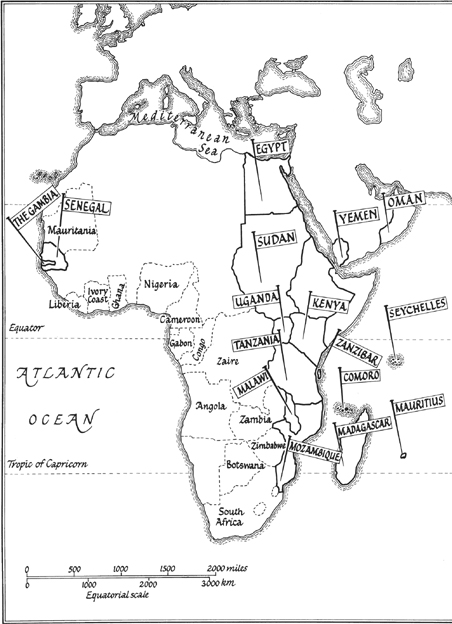

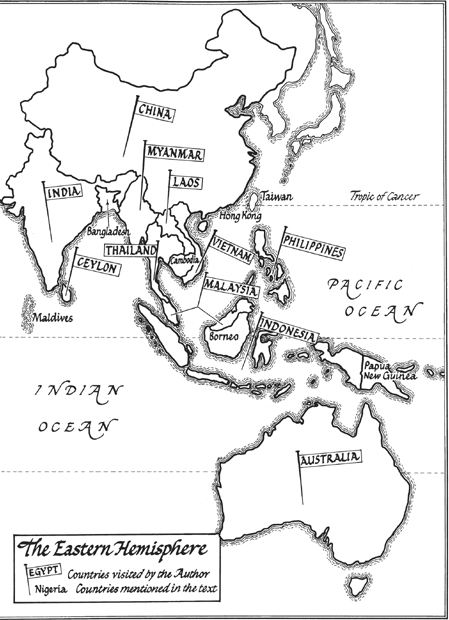

Author photograph Anne Miller Maps by Reginald Piggott

www.vintagebooks.com

v3.1

For Tania and John

Tropic (trop-ik). n. Late ME. tropik; LL. tropicus; Gr. tropikos, meaning belonging to a turn, and tropos, turning, relating to the suns turning at the solstice.

Tropically (trop-ika i), adv. 1852. Hot, sultry or torrid. With tropical heat, luxuriance or violence.

i), adv. 1852. Hot, sultry or torrid. With tropical heat, luxuriance or violence.

Contents

Prologue

For years Frank Clarke, a traveller in bells, had brought a certain plangency to the islands of Oceania. He worked for a London foundry whose Edwardian managers still referred to our part of the world as the Torrid Zone. Out here, Frank liked to say, due to the moist equatorial air and reverberant properties of water, his Clerkenwell bells gained an acoustic bounce and echo found nowhere else. He called it tropical sonance.

Frank turned up one morning aboard a small steamer bound for Tonga. It made an emergency stop at Port Vila and my father, summoned to the ship, returned with Frank slumped comatose in his launch. After administering an intramuscular quinine shot7 grainshe saw him through the cycles of malaria: first the teeth-chattering rigor when they piled on blankets and force-fed him hot fluids, next the acute vomiting and mind-expanding headaches as the clinical thermometer stuck at one hundred and five, finally the heavy sweat after which they changed his sodden sheets, gave him Atabrine by mouth and waited for it to happen all over again. He recovered, but, too weak to travel, left the hospital and came up the hill to recuperate in our house. My father had told us about the Englishman whod cracked jokes at deaths door. My mother, intrigued, had taken him books.

Small, skinny and white-bearded with a shock of uncombed ash-white hair, he had rheumy blue eyeswhich held your own in a very steady wayand a surprising voice: deep, patrician and carrying echoes of the old British ruling class. He told us little about himself. Once he received a letter addressed to Frank Clarke MA (Oxon) yet, when asked what hed studied, he simply said, Oh, something relating to my work. An Oxford degree in bells? That seemed about the size of it. Frank would not be drawn.

Our island, Iririki, lay just a stones throw from Port Vila, and each day he sent Moses, our gardener, off in his canoe to the Burns Philp store for a bottle of Bundaberg rum. This, he claimed, contained all the nourishment he needed. Though my mother badgered himFor Gods sake, Frank, you need building uphe barely touched his food, just moved it distractedly around the plate as he talked. Yet he could make her laugh. The unexpected re-emergence of that sound, like a dry stream bed suddenly in spate again, was a sharp reminder of its rarity. And I noted Franks pleasure when it happened. She was a pretty, brown-eyed woman whose face shone with intelligence, he a wry, gossipy, alcoholic bachelor old enough to be her father. Yet I saw the way his gaze followed her around, and the effort that went into keeping her amused. The entertaining stories never stopped.

Uneasy with children, he simply addressed them as adults and spoke to them about adult matters. For example, sitting under the banyan tree one morning with an unopened P. G. Wodehouse on his lap, he said to me, Do you think your mother is happy?

Id never given the subject a moments thought. She had frequent moods but these were always attributed to neuralgia; then she took APC tablets and went to lie downoften for days on end. It was the most disturbing question Id ever been asked and Frank, doubtless noting my bewilderment, volunteered an indirect answer.

I think the tropics are getting her down.

I stared. The tropics?

Yes. These are the tropics, Sandy, its a region of the world. You live in the tropics. But they dont suit everyone.

He told me a little about our region and its unique relationship with the sun; it was, apparently, the only section of the planet over which it passed directly. Everyone else saw it obliquely, angled and aslant; indeed, during midwinter in the frigid zones it apparently tumbled so far off the perpendicular they never saw it at all. But here, every single day of the year, it rose metronomically at about six in the morning and set twelve hours later, with only the briefest of dawns and dusks.

Frank seemed to imply her headaches were somehow solar-induced or -related yet, when I put this to my mother, she said brightly, Hes talking nonsense as usual. I love it here. You know that. But, years later, I realized he was right.

My mother feared the tropics. The victims of its diseases, often incurable, sometimes disfiguring, were to be seen every day down at the hospital. My sister and I were constantly monitored for a whole sweat of fevers, while our personal hygiene regime included the routine checking of stools for blood; blood probably meant dysentery, which in those days could kill a child in hours. She hated a climate which threatened to make her prematurely old and sallow, and which slowed up her mental processes. Were all at least a beat behind, she would sigh, lamenting too our chaotic behaviour and disorganized personalities. The tropics made you garrulous; everyone, she claimed, talked at oncewhereas in more temperate, reflective latitudes conversations tended to be linear; speakers there took turns.

i), adv. 1852. Hot, sultry or torrid. With tropical heat, luxuriance or violence.

i), adv. 1852. Hot, sultry or torrid. With tropical heat, luxuriance or violence.