Alexander Frater

CHASING THE

MONSOON

A Modern Pilgrimage Through India

PICADOR

Contents

Prologue

The first sounds I ever heard were those of falling rain. It was tropical, the kind that seems to possess a metallic weight and mass, and it began bucketing down as my mother went into labour at a small mission hospital in the South-West Pacific. It continued during the delivery and for some time after my birth, drumming on the galvanized iron roof, swishing through the heavy foliage outside.

The delivery was made by my father, the only doctor for a thousand miles in any direction. Several times a week he attended emergency calls by motor boat, often sailing great distances to reach patients in the remoter villages and settlements. The weather was thus of more than passing interest to him and, using a calibrated glass rain gauge and a creaking anemometer kept in the hospital garden, he measured and recorded it, noting down items like precipitation, hours of sunshine and wind speed and direction.

Years later, referring to these records, he told me that on the day I was born 2.1 inches fell in the space of seven hours and twelve minutes; it knocked flowers off trees and washed away topsoil; our little island was carpeted with fallen blossoms, damp and sweet smelling, the surrounding lagoon darkened by tons of deliquescent earth floating in suspension. The sea state had been moderate, the swell light.

Naturally I have no conscious recollection of these events but reckon they must have left a mark. I spent five years there before the threat of an impending Japanese invasion caused my mother, sister and me to be evacuated to Australia aboard an ageing, rust-streaked tramp steamer (which got under way through light air and a heavy pre-dawn dew) but during that period I experienced thousands of hours of rain and climatic extremes.

Tropical depressions moved in and out like trains, pulling their high precipitation, Force 8 winds and immoderate sea states behind them, and they always got a big welcome from me. The inevitable thunder and lightning overtures were exhilarating but I had been taught to observe them analytically, counting off the seconds between flash and boom at the rate of five to the mile, tracking the approaching storm, anticipating the foaming onset of the rain itself comforting, cooling, charging the house with smells from the dripping garden; perhaps it was atmospheric electricity that sent mysterious squalls of frangipani and jasmine gusting through the rooms and lingering in fragrant air pockets long after the rain had gone. I liked the sense of privacy it invoked, the way towering curtains closed around the island and sealed it off from the rest of the world.

A picture hung beside my bed which accurately encapsulated all this. It was a framed, luridly tinted Edwardian print of a deluge inundating a range of steep grassy hills. Temples along the crests indicated that the landscape was oriental. In small forests lower down, tigers and naked pygmies with spears could be discerned. In some the tigers were avoiding the pygmies; in others the pygmies ran from the tigers. What made it remarkable, though, was the weight and density of the rain. Water fell torrentially from low, scudding cloud and sprang from the hillsides in countless foaming cataracts. Flapping sheets of water hung spinnaker-like in the air, more went surfing down the slopes. Its curious bottle-green opacity suggested that the artist L. Geo. Lopez according to the signature had placed his drowned landscape at the bottom of a lake.

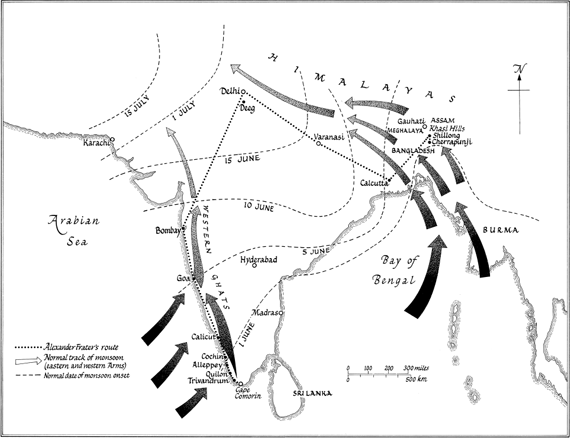

This masterpiece, identified in a flowing intaglio caption as Cherrapunji, Assam: The Wettest Place on Earth, had been a wedding present to my parents. Its effect on me was so profund that afterwards, as a war evacuee in Australia, bouts of homesickness could be assuaged by simply willing it back again. In the minds eye it had a dark iconic glow that dispelled even the darkness of my school dormitory.

My father admired the picture too. He called it a study of convectional turmoil. It was also a view of the Indian monsoon in the act of producing the worlds heaviest rains; what L. Geo. Lopez had depicted here, probably without even realizing it, was the excessive precipitation you got when the upper tropospheric belt moved in over those lofty hills. Travelling, of course, on an oblique bias, my father would say. He knew his stuff. The donor of the picture was an old Glasgow friend named Wapshot who worked in Cherrapunji as a Church of Scotland missionary, and their correspondence seemed to consist largely of exchanged weather information. Some of Wapshots rainfall figures reduced even my father to silence. Thirty-five inches in a single day! Waterlogged earth made burials impossible so corpses were placed in vats of wild honey until the ground was dry enough to receive them. The honey tasted faintly of oranges and, according to Wapshot, lent the bodies a slick, eelike lubricity which made them very hard to handle.

My father often spoke of going to Cherrapunji. In meteorological terms he likened it to one of the Stations of the Cross and implied that a visit at the height of the monsoon, with his rain gauge, would be a kind of pilgrimage.

Two or three times a year, in season, we got a bravura climatic performance of our own. Hurricanes were usually presaged by a red moon, a purple dawn and oily green morning cloud. The sun if glimpsed at all would often be encircled by a halo, its open side announcing the quarter from which the blow should come. The barometer dropped so fast it almost fell off the wall. The sea became glassy and a curious stillness set in. Smoke rose from village fires in a structured, architectural way, forming pillars and buttresses that supported a vaulted ceiling of heavy black overcast. From neighbouring islands the sounds of dogs barking and babies crying carried clearly. Small craft ran for cover. Storm shutters went up.

My father produced the hurricane flags which, traditionally, flew from a staff at the hospital landing white for later (twelve hours to go), yellow for soon (six hours), black for imminent. They were made of Admiralty-quality all-wool double warp bunting, designed to withstand extreme conditions, and it was my job to hoist and lower them. The raising of the black flag was noted by those islanders in low-lying, exposed regions who later might have to climb to the tops of coconut palms, hack off the fronds and tie themselves on. Streamlined trees presented no obstacle to the wind; giant waves would surge by harmlessly below.

Only once did we experience the feared vortex, or eye of the storm, which passed overhead as precisely as an aircraft locked on to a radio beacon. Before the anemometer pole snapped like a sapling it was registering 130 knots, or double the maximum force on the Beaufort scale. A mill-race sea burst over the island, and the wind railed so deafeningly we had to communicate by lip-reading. It struck the house with heavy shocklike impacts that made it shudder and creak; during the most violent it felt like a ship under way, destabilized, rocked by small pitching movements, the roof flexing and tugging and warping its pitchpine rafters. Our anxiety about the roof was heightened by the fact that others were losing theirs; we saw four hundred square feet of Cambridge blue corrugated iron, previously the property of Mr Tallboys at Public Works, pass the end of the garden then make a steep climbing turn as it headed away south towards Australia.

And yet throughout all this I noted a special light in my fathers eye. He may have been worried but he was exultant too. So was I. For dedicated fans of the weather this was great stuff, a classic performance witnessed from grandstand seats.

Next page