Dedicated to the memory of Harry A. Logan Jr of Warren, Pennsylvania

CONTENTS

Maps by Leslie Robinson

Turn a map of the world upside down and the Indian Ocean can be seen as a vast, irregularly-shaped bowl, bounded by the shorelines of Africa and Asia, the islands of Indonesia, and the coast of Western Australia. Unlike the Atlantic and Pacific, merging at their extremes into the polar seas, this is an entirely tropical ocean; to mention it calls up a vision of palm-fringed islands and lagoons where rainbow-hued fish dart amid the coral. That is the tourist-brochure image, but behind it lies the Indian Ocean of history a centre of human progress, a great arena in which many races have mingled, fought and traded for thousands of years.

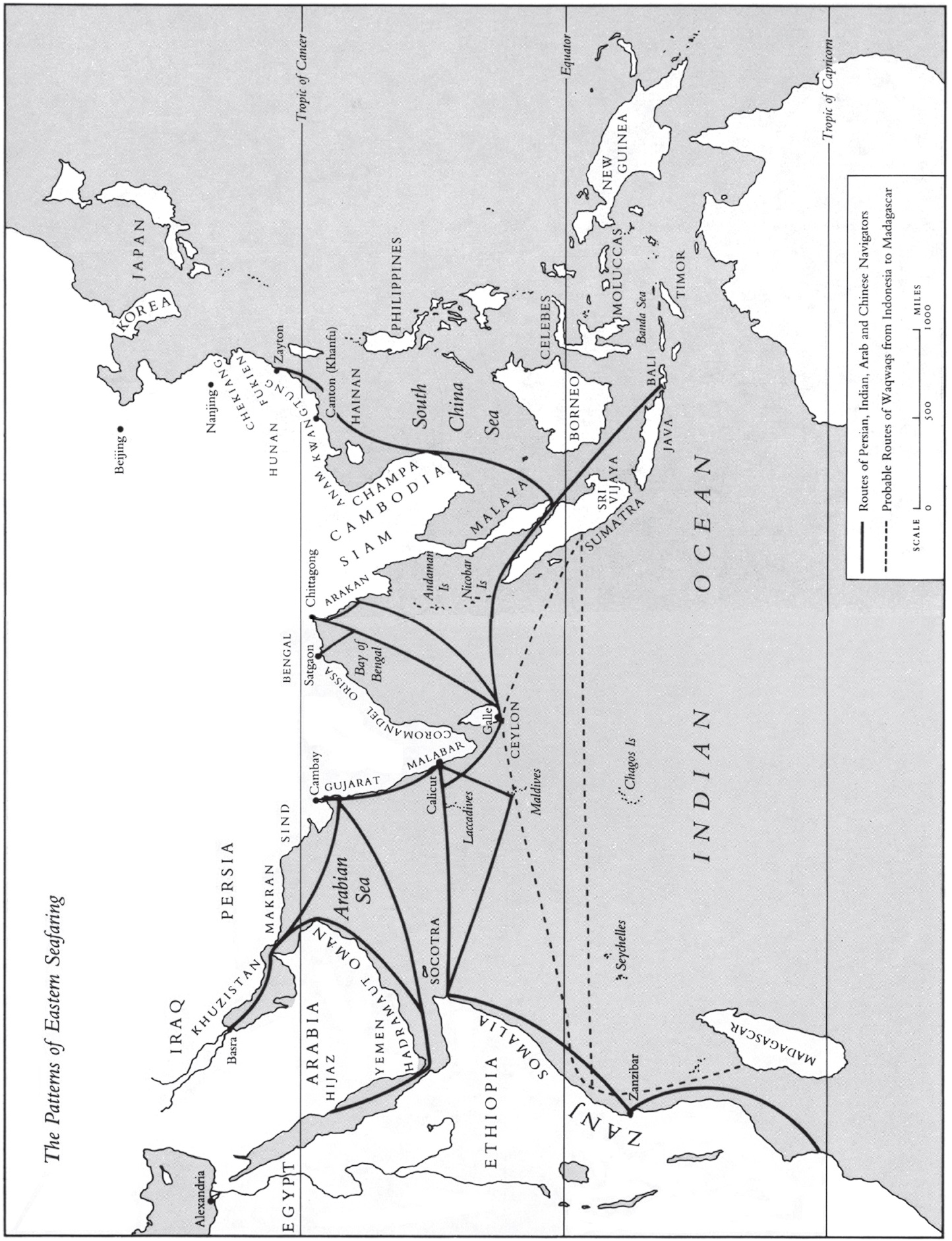

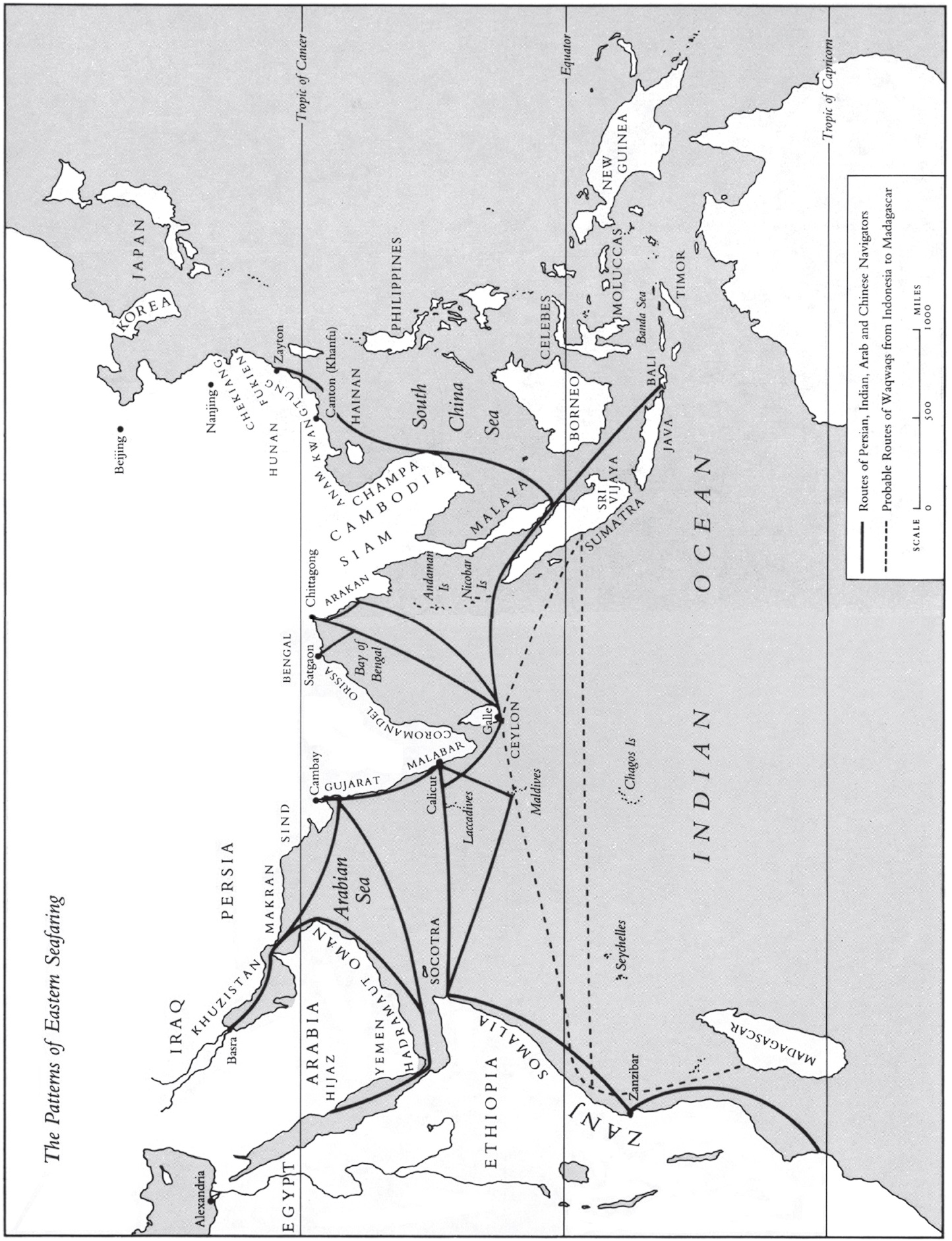

The earliest civilizations, in Egypt and the valley of the Tigris and Euphrates, had direct access to the Indian Ocean by way of the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf. At the hub, stretching towards the equator, lay the Indian sub-continent, itself the site of ancient cultures in the Indus valley. Since long before the time of Alexander the Great, travellers had brought back tales of the rich and voluptuous East. The emperor Trajan, arriving triumphantly at the Persian Gulf in A.D. 116, and watching mariners set sail for India, had mourned that he was too old to make the voyage and gaze upon its wonders.

For almost a thousand years after the fall of the Roman empire the western side of the Indian Ocean, the focus of this book, was as much an entity as the Mediterranean, surpassing it in wealth and power. The arts and scholarship flourished there, in cities to which merchants came from all corners of the known world. There was also much turmoil, as conquering armies spawned in the remote parts of Asia swept down to overthrow old empires and impose new dynasties.

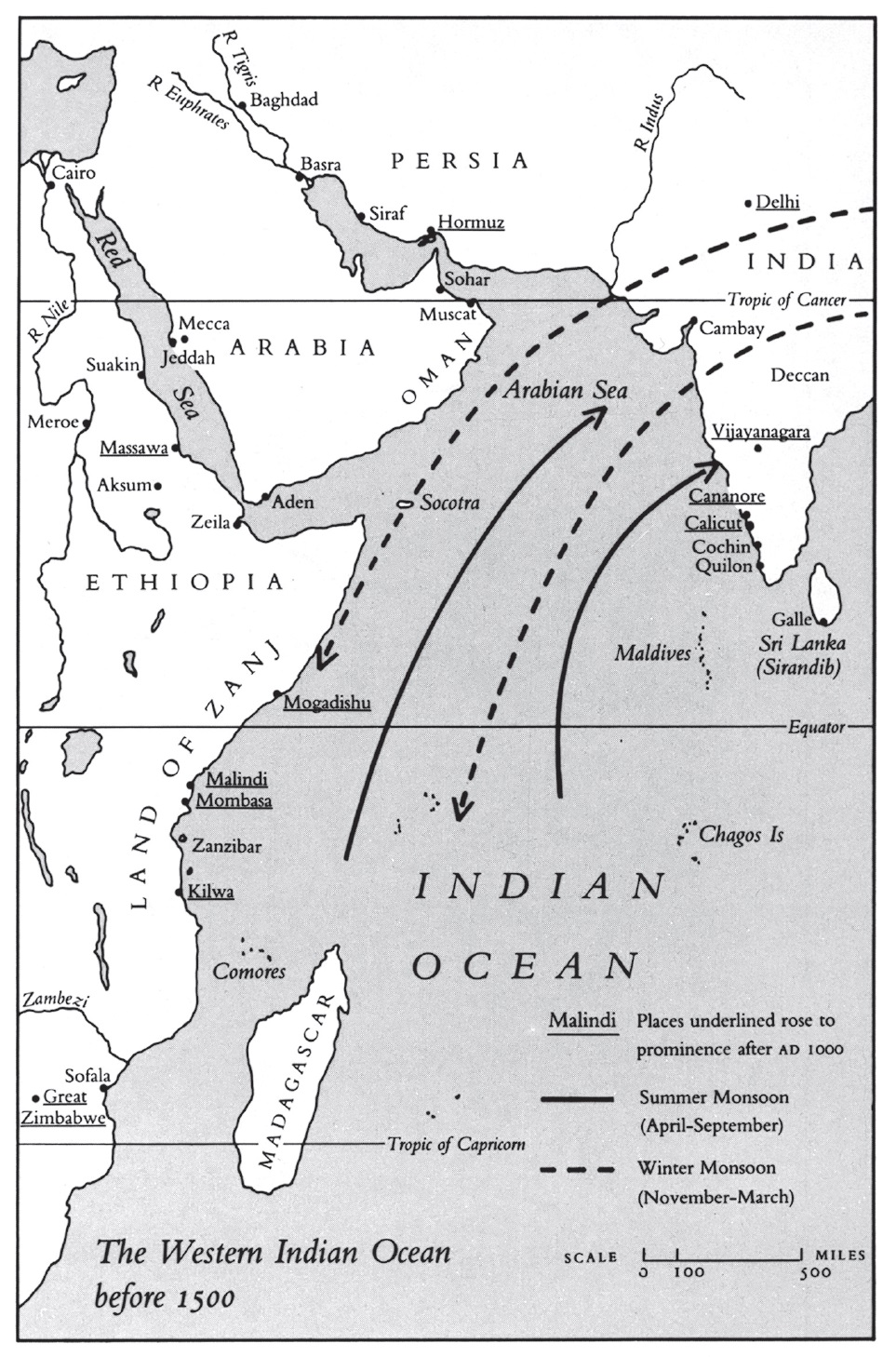

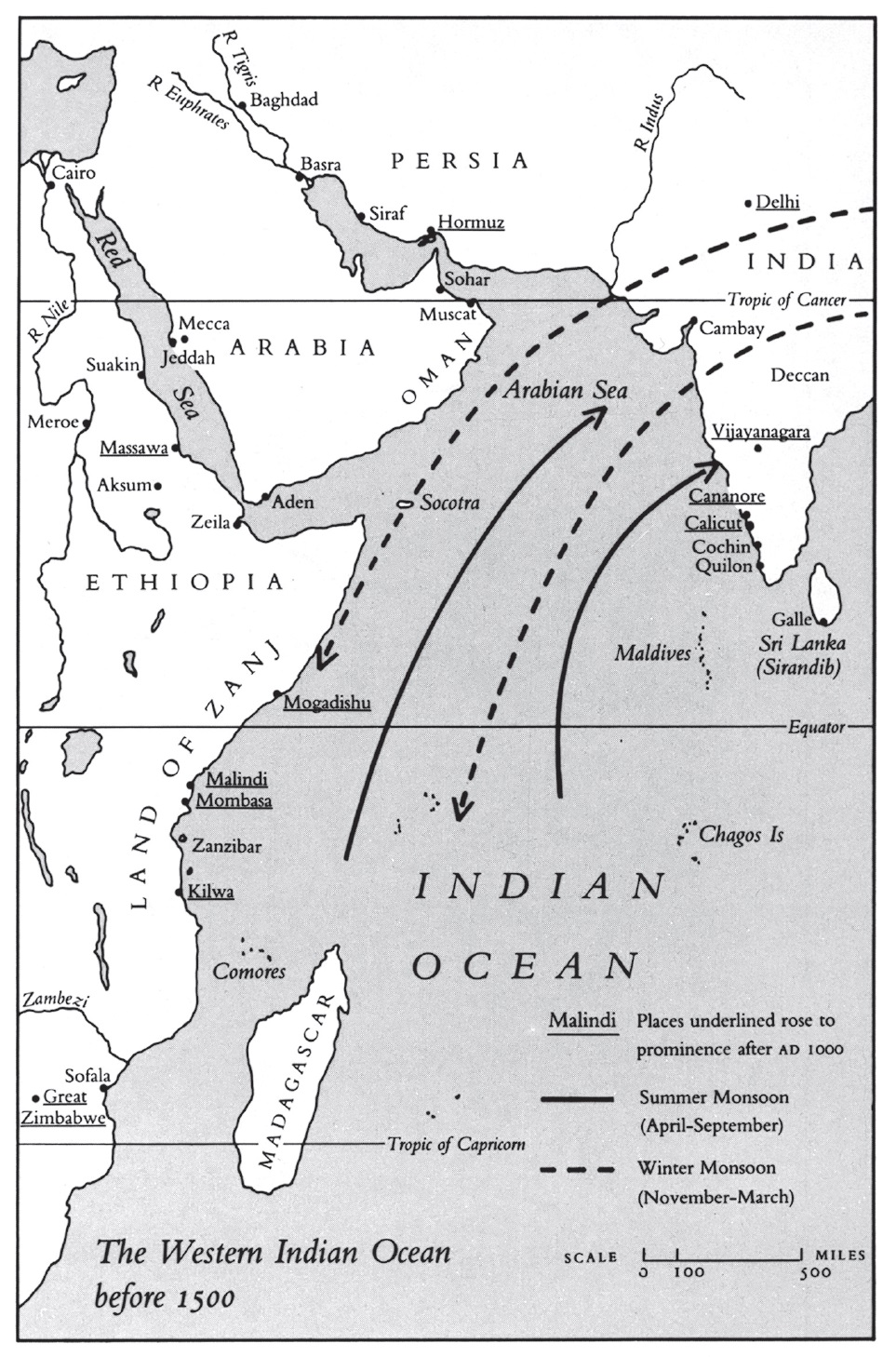

The lives of ordinary people, however, were always ruled more by nature than by great events, by the perpetual monsoons rather than by ephemeral monarchies. The word monsoon comes from the Arabic mawsim, season, and ever since sailors had dared to venture on voyages across the open seas these seasonal winds had borne their ships between India and its distant neighbours. For six months they blow one way, then in the reverse direction during the other half of the year. The summer monsoon, coming from East Africa and the southern seas, is pulled eastwards by the rotation of the earth after passing the equator, so that it sweeps across India and up through the Bay of Bengal. Winds are fiercest between June and August.

The sea-captains of old might not understand why the monsoons happened (how colder air was being sucked northwards over the ocean in summer towards the hot lands of Asia, then southwards from the Himalayas and the Indian plains in winter); for them it was sufficient that the winds came on time, year in and year out, to fill their sails. For the farmers of India it was likewise enough to know that the summer monsoon would bring them rain. However, on sea and land, the monsoon was always feared in its times of fury, when no vessel dared set out, when floods swept away villages, and cyclones left devastation.

It might be argued that the inescapable rhythm of this climate induced a certain fatalism among the Indian Ocean peoples. Yet the monsoon has also long been recognized as one of natures most benign phenomena a subject worthy of the thoughts of the greatest philosophers, in the words of John Ray, a seventeenth-century English scientist.

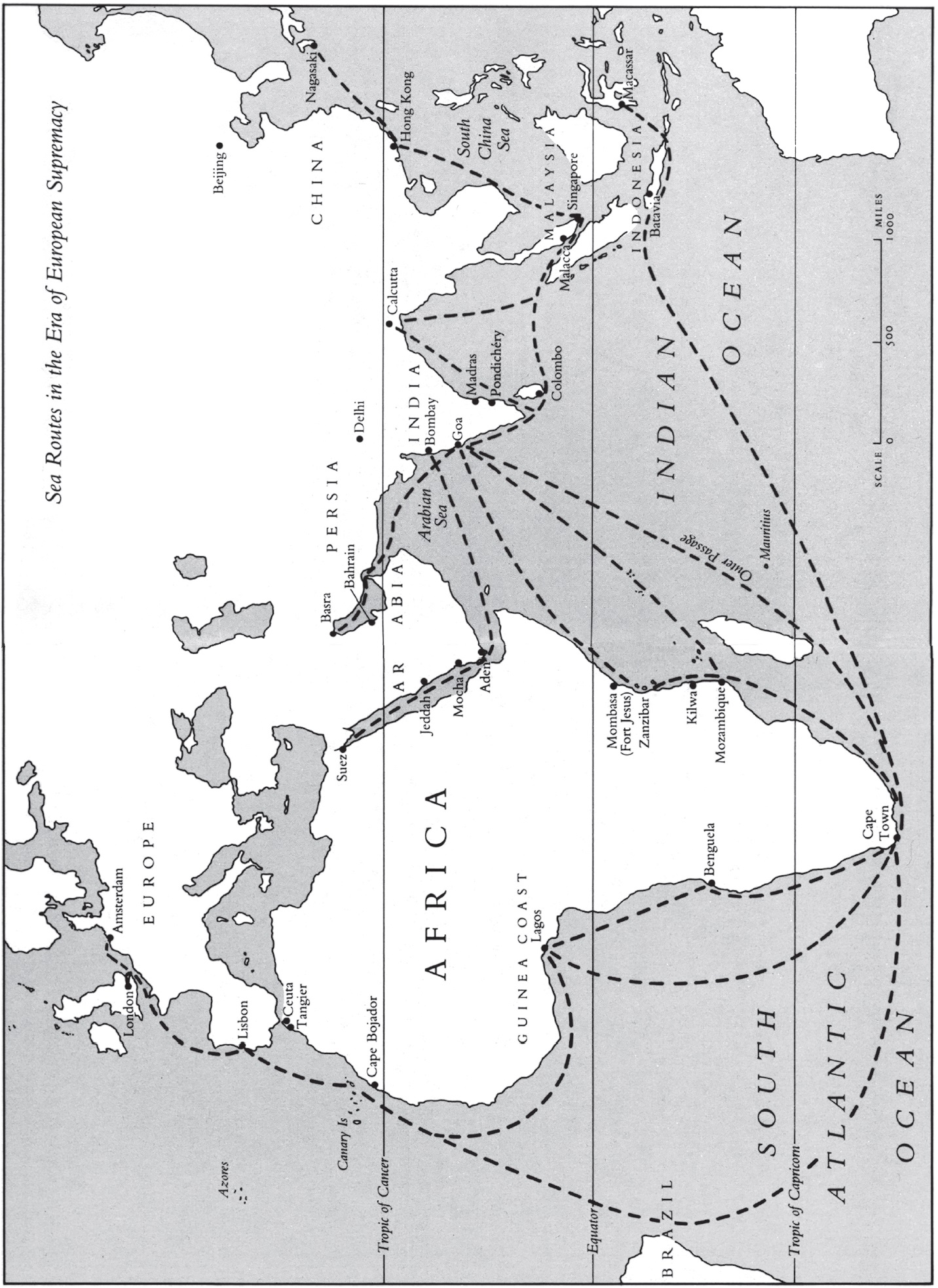

Until the Age of Discovery, there had been a thousand years of almost total ignorance in Europe about the Indian Ocean and the lands encompassing it. Once, during the heyday of the Roman empire, a flourishing trade had existed with the East, conducted mainly by Greek mariners who had learned how to use the monsoons.

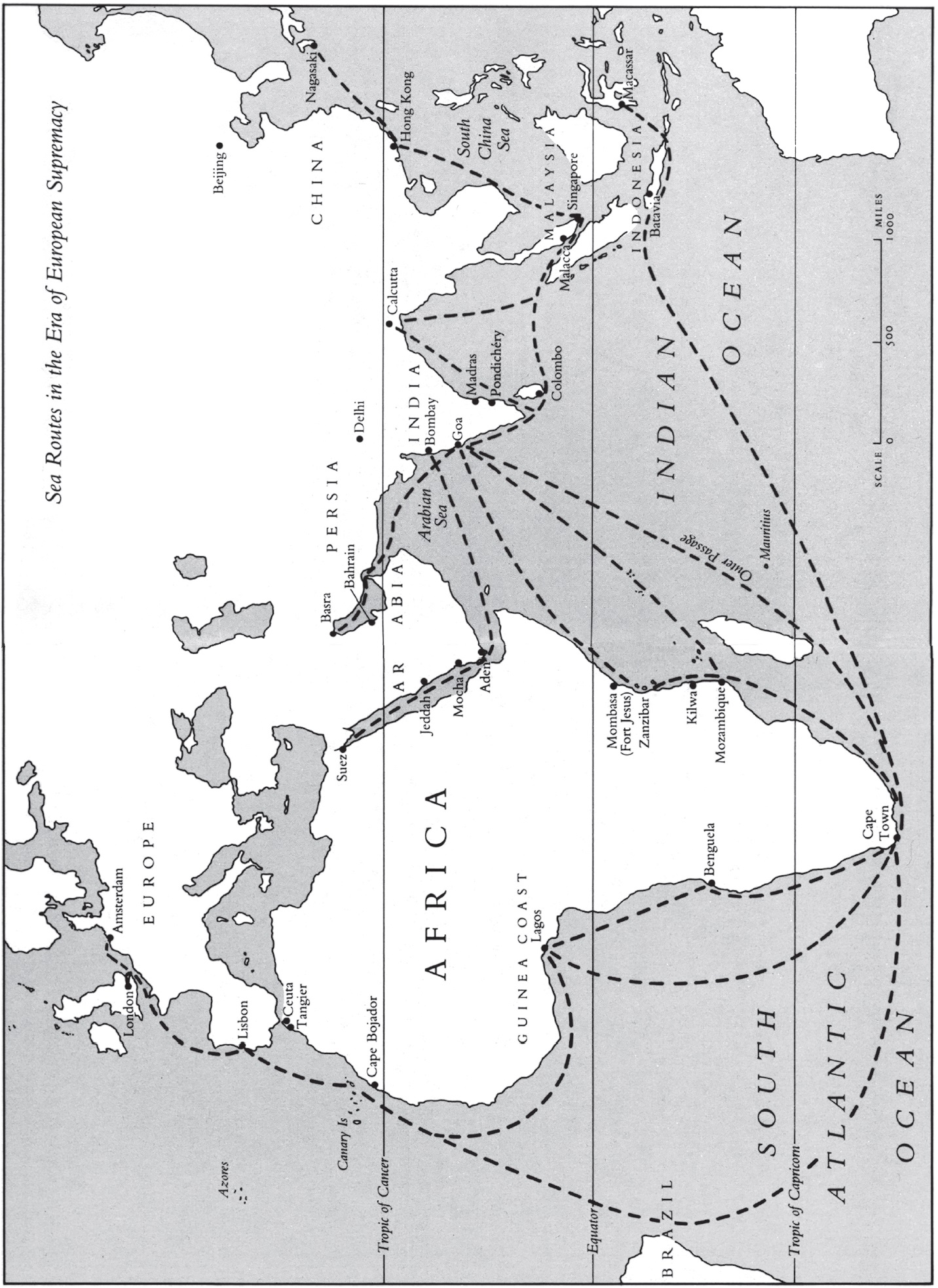

When medieval Europe started looking for a new route to India, to outflank Islams barrier across the Middle East, its navigators were long thwarted by the great bulk of Africa, until the Portuguese finally rounded the Cape of Good Hope. Vasco da Gamas voyage to India and back in 149799 was by far the longest sea journey ever undertaken by Europeans.

This book shows how the European presence from the sixteenth century onwards changed Indian Ocean life irrevocably. Thriving kingdoms were subdued and former relationships between religions and races thrown into disarray. With the advent of western capitalism, ancient patterns of trade soon became as extinct as the dodo (which Dutch sailors had unceremoniously wiped out on the island of Mauritius). Yet although the guns of Europe could create new empires in the East, the populations there were too great to be held down permanently. What happened in the Americas was never going to be repeated in Asia. The record of European intervention and the response to it is made up of violence, depravity and courage.

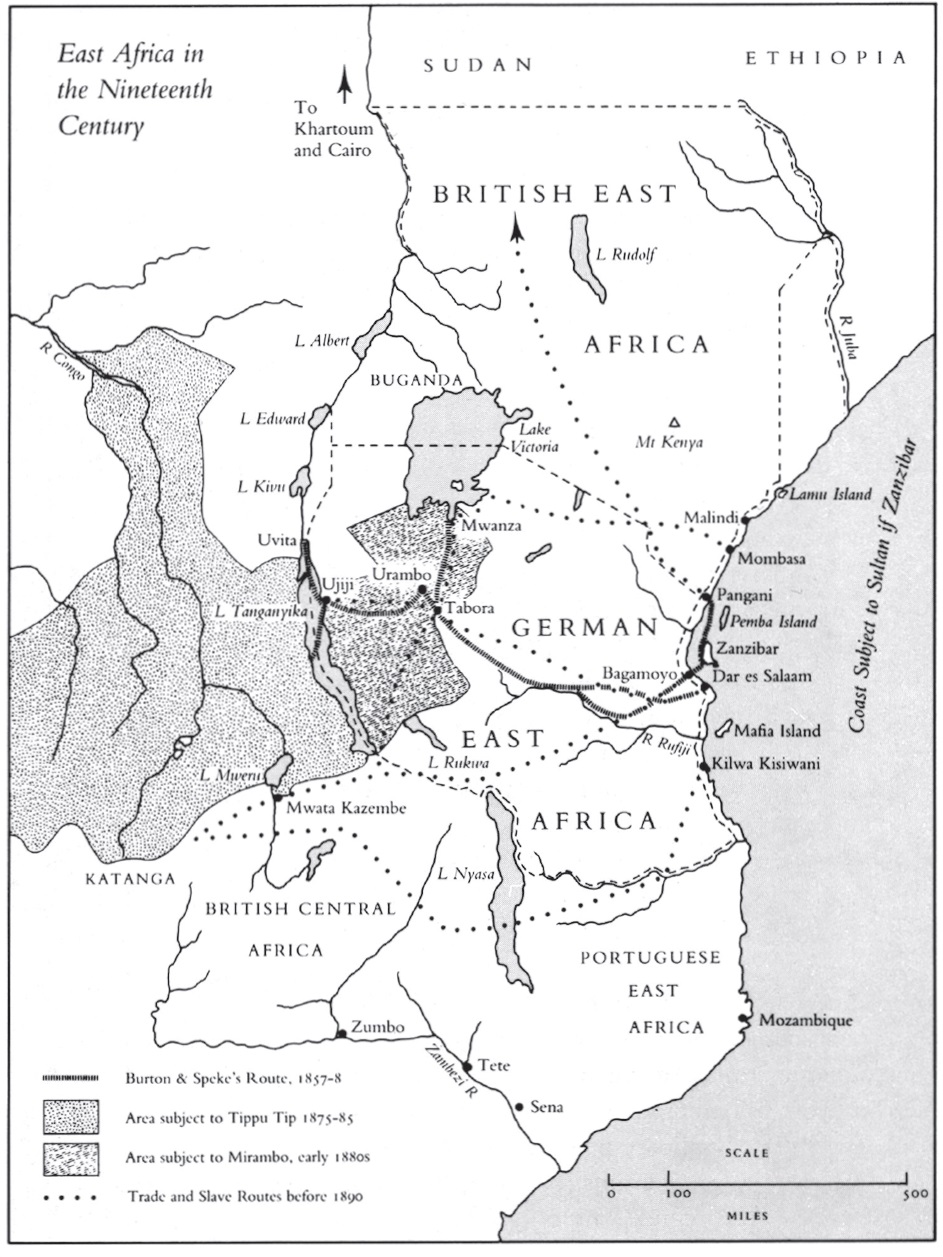

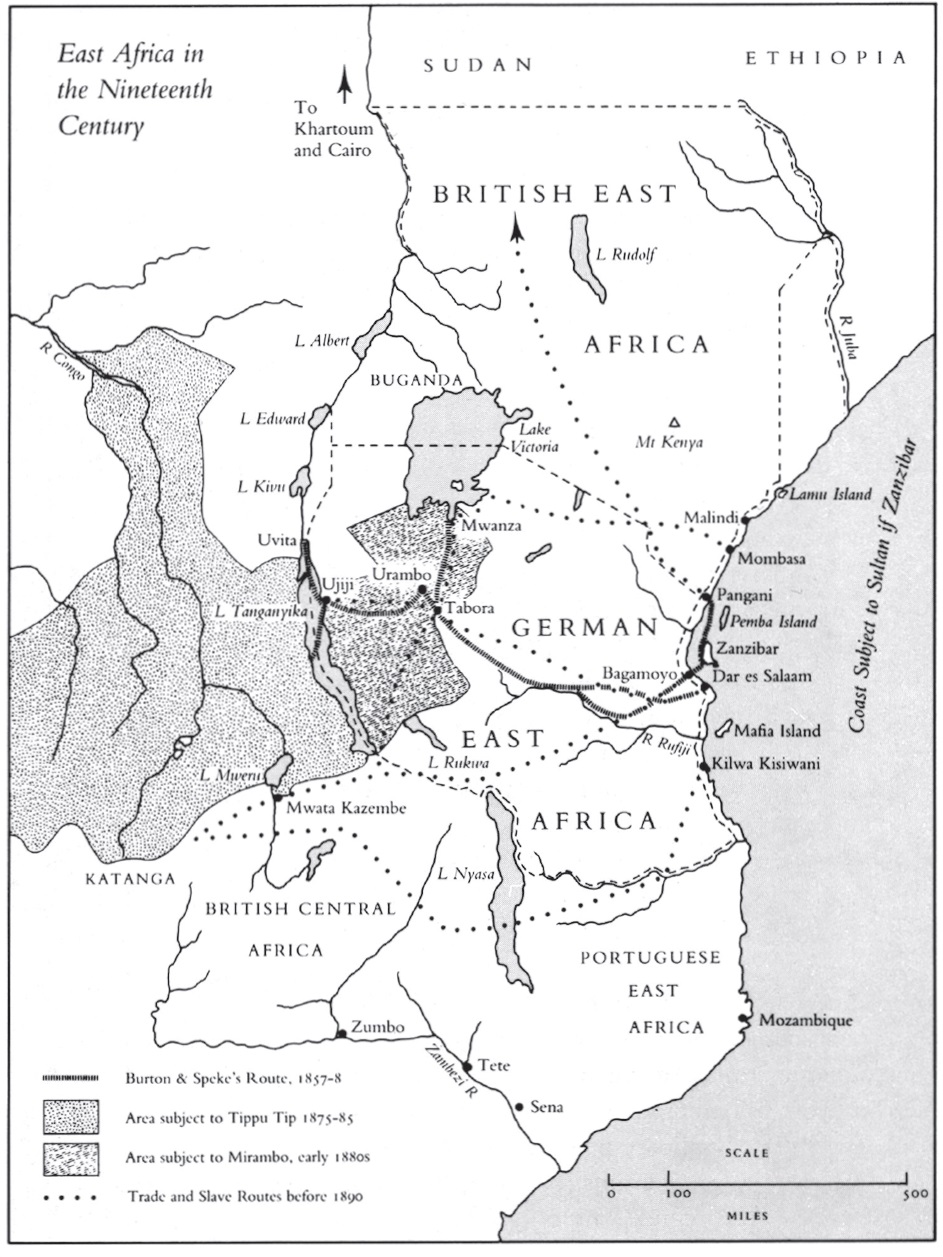

Through thousands of years of change in the Indian Ocean arena, the African giant forming its long western flank was rarely anything other than a mute bystander. Its interior was terra incognita, its peoples excluded from fruitful dealings with the rest of the world. Since the eighth century, Africas contact with the Indian Ocean had come under the sway of scores of Arab-ruled trading ports, strung along two thousand miles of coastline from Somalia to beyond the Zambezi river delta. These settlements looked to the sea; the interior of the continent interested them only as a source of ivory, gold, leopard-skins and slaves. For three hundred years after the arrival of the Europeans, little happened to alter that pattern.

But Africa south of the equator has been twice liberated since the mid-nineteenth century: first from its isolation, then from a colonialism which, although short-lived, seemed to have forged unbreakable bonds with the North, with Europe. Now the monsoons of history are blowing afresh, as the balance of world power swings back to the East. The start of the twenty-first century is seen as ushering in a new Age of Asia, in which the natural unity of the Indian Ocean can once more assert itself. This is the arena where the full potential of the peoples of sub-Saharan Africa will be put to the test.

Where versions of names converted from non-roman scripts are widely recognized, they are adhered to: for instance, the spelling Mecca is used rather than Makkah, even though the latter is more exact. Likewise, the renowned sultan of Zanzibar in the second half of the nineteenth century should strictly be entitled al-Sayyid Said, but his name was always Europeanised as Seyyid Said. For other transliterations from Arabic the Encyclopaedia of Islam is generally followed, but without diacritical marks. With Chinese names the modern pinyin romanization has been adopted so that the admiral formerly known in English as Cheng Ho appears as Zheng He. Most prefixes to root words in African languages are omitted for simplicitys sake.

Portuguese monarchs and princes are, in the main, referred to by the familiar anglicized versions of their names. Lesser beings are left in the original.

Geographical terms accord as far as possible with those in use at the times being written about. Thus Ceylon describes the island which became Sri Lanka in 1972. There is often a wide divergence between early European attempts at Indian names and those employed today; an example is Calicut, the once renowned port which appears on modern maps as Kozhikode.