To the Dark One, Goddess of Time, She who ultimately devours the greatest of empires and the mightiest of kings

1

Introduction

In AD 731, the prosperous Pallava kingdom in southern India faced an existential crisis. The Pallava king, Parameswara Varman II, had died suddenly without a direct heir. He had been on the throne for barely three years and it is likely that he had been killed in a raid by the Chalukya crown price, Vikramaditya. There was a grave danger that neighbouring kingdoms would support rival claimants to the throne and then gobble up territory in the ensuing civil war.

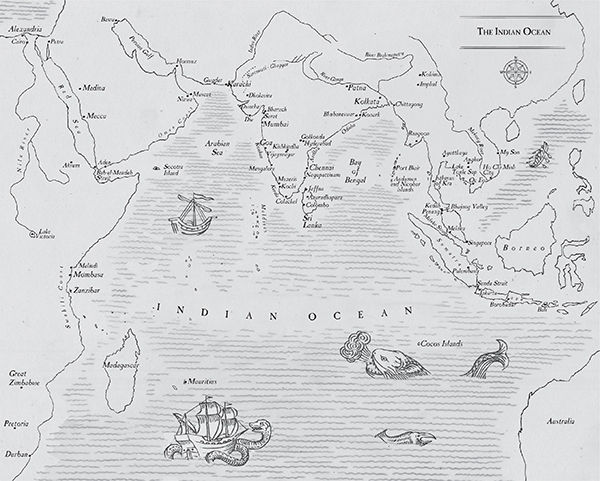

The Pallava dynasty had carved out a sizeable kingdom in AD sixth and seventh centuries covering much of what are now the states of Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh and southern Karnataka. Although it was not as large as some of the great empires of Indian history, what the kingdom lacked in size, it made up with its commercial and cultural vigour. The capital at Kanchipuram, 70 kms west of modern Chennai, was adorned with awe-inspiring temples. Its main port at Mahabalipuram (also called Mammalapuram, 60 kms south of modern Chennai) was busy with merchant fleets from across India and South East Asia, and even from as far as China and Arabia. However, in AD 731, it looked like the kingdom was about to collapse.

A grand assembly of leading scholars, chieftains and other prominent citizens deliberated the matter in Kanchipuram. The discussions went on for days. In the end, it was decided that the best option was to reach out to a collateral branch of the dynasty that had survived in a distant land. Five generations earlier, a young prince called Bhima, younger brother of the great Pallava king Simha-Vishnu, had gone to a distant kingdom, married a local princess and become its ruler. The grand assembly now hoped that they would be able to persuade one of Bhimas descendants to come and wear the Pallava crown.

A delegation of Brahmin scholars was prepared and must have hurried to Mahabalipuram in time to catch the turning monsoon winds. We are told that the delegation then undertook a long and arduous journey crossing rivers, jungles, mountains and deep seas to reach the court of Bhimas descendant, Hiranya Varman. There the envoys put forward their proposal. It so happened that Hiranya Varman had four sons and each of them was asked in turn if he was interested in taking the crown. The first three refused, daunted perhaps by the idea of a perilous journey and an uncertain future in a far-off kingdom. The youngest prince, however, took up the offer. He was barely twelve years old.

The delegation now hurried back to Kanchipuram where a rival claimant called Skanda was trying to establish himself. The usurper was defeated and the young prince was crowned as Nandi Varman Pallavamalla (or Nandi Varman II). There were probably many people who doubted his claim to the throne, which may explain why his later inscriptions would emphasize his pure Pallava lineage. He also faced constant threats from rival claimants and external enemies, particularly the Chalukyas, and may even have spent some time in exile. Nevertheless, Nandi Varman II would eventually claw back the kingdom and become one of the greatest monarchs in the history of southern India. In this he was helped by a talented general Udayachandra, possibly a childhood friend who may have accompanied him from his country of birth. Nandi Varman II would rule his kingdom until AD 796 and preside over an economic and cultural boom.

We know about the remarkable tale of how a foreign prince was invited to rule over a kingdom in southern India because Nandi Varman II himself tells us the story in inscriptions and bas-relief panels on the walls of the Vaikuntha Perumal temple in Kanchipuram. The temple is a little away from the main thoroughfare of the town and I found myself there on a windy January afternoon. The temple was closed for the afternoon but two friendly priests kindly let me in when I explained that I had come a long way to see the sculpted panels. So I spent a couple of hours alone reading the story narrated by the panels.

What struck me were the unmistakably oriental facial features of many of the depicted individuals. For instance, there is a prominent figure of a Chinese traveller. The temple priests were convinced that it showed the famous Chinese pilgrim Xuan Zang (also spelled Hiuen Tsang). It is quite possible that they are right since we know from Xuan Zangs diaries that he had visited Kanchipuram a few decades before the temple was built but, given the volume of international trade and exchange that passed through Pallava ports, it could well be another Chinese visitor. However, what I found even more interesting about these panels were the obvious parallels with Khmer art. Anyone who has also visited Angkor and other sites in Cambodia would not fail to notice the similarities.

The close link between the Pallavas and the Cambodians is well known; even the Khmer script is derived directly from the Pallavas. There is also plenty of evidence of Pallava links with other parts of South East Asia. For instance, an inscription by Nandi Varman II has been found near the Thai-Malaysian border. This was once part of the HinduBuddhist kingdom of Kadaram in what is now Kedah, Malaysia. Usually historians assume that these connections were limited to trade and culture, but is it possible that Nandi Varman II was from South East Asia? It turns out that there is some reason to believe that not just Nandi Varman II but the Pallava dynasty itself may have had its roots in the region!

Scholars have long debated the origins of the Pallavassome claiming local roots while others have speculated on north Indian or Parthian ancestry. There are several founding myths but all of them agree that the dynasty began with a marriage to a princess from a Naga or Serpent clan from across the seas. A Pallava inscription clearly suggests that the dynasty derived its royal legitimacy from this alliance. While scholars have spent a lot of effort trying to speculate on the patrilineal origins of the dynasty, the Pallavas themselves seem to have placed greater emphasis on this matrilineal link to Naga royals.

So, where did this Naga princess come from? Most historians give little thought to female lineages and simply assume that she must have come from some small kingdom in nearby Sri Lanka. The word bhujang is a Sanskrit synonym for naga, which means the area is literally called the Valley of the Serpents.

Whether Cambodian or Malay, it suggests that the Pallavas had been repeatedly marrying into the Naga royal clan. Nandi Varmans ancestor Bhima, in other words, had not sailed off to an unfamiliar land but to a country with which the Pallavas already had close family ties. This may explain why Nandi Varman II was able to make the claim that he was a pure Pallava from both his fathers and mothers lines. Not only was he a descendant of the Pallava prince Bhima, he was also the son of a Naga princess, the original source of the dynastys royal legitimacy.